The list of newsworthy sports accidents with ensuing knee damage reads like a Who's Who of the commonest knee injuries. A recent example that has attracted a great deal of media attention is that of the German and Real Madrid footballer Sami Khedira, who had a bad fall at an international match in Italy in November 2013. Less than 24 hours after the event he underwent surgery, having been diagnosed with torn anterior cruciate ligament and torn medial ligament of the right knee. Since then, the doctors have said that the healing process has been "satisfactory" and he bounced back in the Champions League final in Lisbon on Saturday.

For Khedira's colleague, Holger Badstuber, who has suffered two cruciate ligament tears and had four operations since 2012, things have not gone so well: plenty of rehabilitation, but little prospect of the longed-for participation in next month's World Cup in Brazil.

Injuries incurred by Sami Khedira and others have focused media attention on knee problems, exemplified by the cover of the May 2014 edition of the German Radiological Society's magazine for patients.

Injuries incurred by Sami Khedira and others have focused media attention on knee problems, exemplified by the cover of the May 2014 edition of the German Radiological Society's magazine for patients."Football is one of those sports in which the knee is at greatest risk," explained Dr. Erich Rembeck, a specialist in orthopedics and sports medicine from Munich, as well as orthopedic coordinator for the German Football Association. "This is mainly because the players always have to react to situations with an unforeseen lateral stress. Then there is a continual stop-go rhythm, with the players running fast and halting abruptly."

Besides football, another sport where knee injuries are common is skiing. Sometimes the outcome is good, as with the skiing star Maria Höfl-Riesch. After a cruciate ligament tear and meniscus damage, she was never on better form; she won gold at the Sochi Winter Olympics in 2014. Her friend and colleague Lindsey Vonn was less fortunate.

After bad falls and two cruciate ligament tears, she had to abandon all her Olympic dreams shortly before Sochi, a decision sports' experts consider very sensible. With an unrepaired cruciate ligament, the knee lacks stability and sensitivity. For a while, peak fitness and strong thigh muscles might compensate -- but this is the very point where cartilage degeneration begins.

Knees: Always giving trouble

Whether we step forward briskly, stop abruptly, or turn round suddenly, the knee takes part in every movement. Nature has not equipped it especially well for this unrelenting use. The purely physiological reason is that the knee's position between the relatively long thigh and lower leg exposes it to unfavorable leverage conditions. So every load that the muscles of the leg and bottom do not absorb, plus about two to three times our body weight, lands unchecked on the knee, or more accurately on to two areas the size of a coin. These are the dimensions of the area where the femur and the tibia come into contact: an elaborate apparatus of tendons, ligaments, bones, and buffers.

Not surprisingly, the knee is our real Achilles' heel. The effect of this is twofold: The joint is extremely prone to injury, and sports injuries almost always involve the knee, especially the ligaments (cruciate ligaments, lateral, and medial ligaments) and tendons, which have the task of stabilizing the knee. The meniscus, an elastic fibrous cartilage sitting within the knee laterally and medially, is also prone to injury. It functions as a shock-absorber, enlarges the load-bearing area, prevents friction, and so protects the bone.

Even if we have never in our lives had a bad fall or foot sprain, another phenomenon makes the knee vulnerable: like any joint, it is susceptible to wear-and-tear. A lubricating layer 3 mm to 4 mm thick, the cartilage tissue is responsible for preventing friction between the femur and the tibia. If this cartilage thins, for whatever reason, osteoarthritis develops. Falls and wear-and-tear are two main problems with knees. Quite often they coincide, with osteoarthritis not fully manifesting itself until an injury has occurred.

A previous fall is not the only cause of accelerated cartilage degeneration. Being overweight and having poor posture, knock-knees, bandy legs, too little exercise, or exercise of the wrong sort can all thin the elastic layer between the bones. This means that a frictionless sequence of movement is no longer guaranteed and the bones are not sufficiently protected from knocks. If the cartilage is completely worn away in places, the bones rub against each other unprotected. This degeneration is insidious and passes through many different phases. Depending on the diagnosis, something can be done to improve the situation where there is pain and limitation of movement.

Good diagnosis is halfway to a cure

If a patient has had a fall, has unexplained pain, or simply can no longer move properly, the orthopedic specialist is the first point of call for knee problems. The specialist will first make a note of the problem, and the next thing after that is almost always imaging.

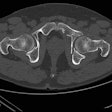

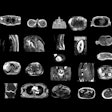

"For monitoring and classification, especially with arthritis, and possibly for surgery, an x-ray is appropriate in the first instance. However, it will not, for example, show 2D cartilage damage," said Dr. Axel Stäbler, a professor of radiology from Munich. "This is why the method of choice is almost always MRI or CT. These devices give high resolution in thin layers and can show with great precision what is going wrong with the knee. Practically no injury can escape the MRI scanner."

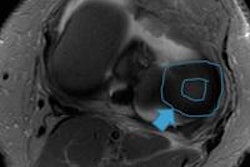

These images show the three most common knee injuries. Left: Osteoarthritis. On the x-ray, the osteoarthritis is clearly recognizable, with the narrowed joint space. Right: Lateral ligament tear. MRI shows the torn lateral ligament (black arrow). The medial ligament (white arrow) is still intact. Copyright of all images: Universitätsklinikum Essen.

These images show the three most common knee injuries. Left: Osteoarthritis. On the x-ray, the osteoarthritis is clearly recognizable, with the narrowed joint space. Right: Lateral ligament tear. MRI shows the torn lateral ligament (black arrow). The medial ligament (white arrow) is still intact. Copyright of all images: Universitätsklinikum Essen.

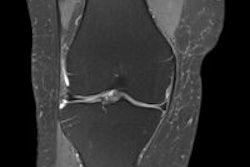

Anterior cruciate ligament tear. MRI reveals a swollen cruciate ligament; the knee joint can no longer be stabilized.

Anterior cruciate ligament tear. MRI reveals a swollen cruciate ligament; the knee joint can no longer be stabilized.The next job for the radiologist and later also for the orthopedic specialist is to correlate the images with the patient's symptoms and find a suitable therapy. The reason, as Stäbler makes absolutely clear, is that "the patient is always right; the question is to get the symptoms under control. To do this, the doctor must also feel the knee and interpret any swelling or redness correctly. This, together with the images, will set him on the right track."

Preventive measures are essential for the knee. Strong thigh muscles and a cartilage layer that is as intact as possible will protect the knee, both from falls and from wear. Two factors are decisive for the knee, according to Rembeck.

"It is essential to reduce excess weight. If you weigh too much you will unknowingly put strain on the knee for years and cause it to wear down," he noted, adding that well-developed leg muscles are also important. "They stabilize every step you take and this all adds up over time. Strong muscles absorb about 30% of the stress which would otherwise be borne by the knee."

Also, the joint cartilage feeds on regular movement. In a sitting position it gets no nutrients and degenerates faster, Rembeck said. "It's like cars. They can't move without oil either."

There are many other ways of controlling knee problems in the first instance, without resorting to surgery. Cold compresses or ice packs bring swift relief, and drugs like diclofenac or ibuprofen can ease acute pain. Physiotherapy or lymphatic drainage can strengthen the knee and reduce swelling. Orthotics can improve the position of the foot and alleviate pain when walking. Joint-stabilizing bandages are also helpful.

Finally, you can actually "feed" the cartilage. Vials of collagen and rosehip in liquid, capsule, or powder form, can curtail inflammation. Studies have also shown that amino acids, if taken long term, can improve the water content in the cartilage, thus making it more resistant.

Sometimes surgery is unavoidable

If nothing helps, the inevitable question is "Should I have an operation?" The answer depends on each individual case. A torn cruciate or medial ligament makes the joint so unstable that surgery is inevitable; the same applies to very advanced osteoarthritis with severe pain. The good news is that in more than 90% of cases, the operation is minimally invasive, without the need for open surgery. In the majority of cases, it is possible to start exercising shortly after surgery with physiotherapy or rehabilitation.

Many knee problems can be controlled with injected medication: hyaluronic acid, for example, can help stop degeneration. Cortisone is effective for inflammation and swelling. Also, growth factors derived from a patient's own blood serum can be injected into the joint, and current studies and previous experience suggest this is a promising approach. But the right activity is still the most important thing. A bit of discomfort is normal, but there should be no pain. In any event, plenty of exercise is top priority for knees to keep them healthy or make them better.

The most common knee operations are:

Arthroscopy: At the same time the camera is introduced into the joint, the joint can be irrigated or damaged parts of the cartilage smoothed (in osteoarthritis). A tear in the meniscus can also be repaired in this way. Postintervention: one to two weeks on crutches to relieve strain on the knee joint, which should be mobilized immediately.

Cartilage replacement therapy: This is used for injuries or arthritis and involves a two-stage arthroscopy. In the first stage, a piece of tissue is taken from an area of the cartilage surface that is not subject to stress. This is propagated in the laboratory. The newly cultured cartilage is embedded in nonwoven fabric for a period of about three weeks. The fabric is then implanted during a second arthroscopy. Postintervention: six to eight weeks on crutches; rehabilitation required. It has a life span of about 10 years.

Implants: made of synthetic or biological material and used for meniscal or ligamentous injuries. Postintervention: three to four weeks on crutches; rehabilitation required. Has a life span of several years.

Artificial joint: partial or unicondylar knee replacement or full knee replacement (artificial knee). Normally the operation is minimally invasive. Postintervention, depending on complexity: three weeks to three months on crutches and intensive rehabilitation. Has a life span of eight to 10 years.

To find out a patient's risk of osteoarthritis of the knee, the following five questions should be asked: Do you carry out an activity that requires frequent kneeling? Have you had an injury, such as meniscus damage? Are your legs misaligned (knock knees or bandy legs)? Does your knee sometimes feel "rusted up" in the morning after you get up? Have you often had pain or swelling in the knee after long walks? Any patient who has answered yes to one or more of the questions has an increased risk of osteoarthritis. If the patient replies yes to questions four or five, the osteoarthritis is already detectable. In either case, patients should definitely see their doctor.

Good versus bad sports

These activities are of benefit to knees:

Swimming, aqua jogging, aqua aerobics. These are ideal forms of exercise. The upward thrust of the water takes the pressure off the joints and the resistance of the water strengthens the muscles. Every movement is easier in the water and can be carried out without pain, giving a greater sense of security. The pressure of the water decongests the blood vessels and reduces swelling in the case of joint effusions.

Walking/Nordic walking is fine if the length of the walk, the tempo, and the gradients are adapted to individual requirements. Serious overweight, weak ligaments, or muscles can strain the joints, in which case a switch to Nordic walking with poles is essential. They relieve strain on the leg joints. Also, the muscles of the torso and arms are used, burning calories and increasing stamina.

Cycling: best done in the open, but also beneficial on an exercise bike, as most of the body weight rests on the saddle. The constant alternation between load-bearing and relief of load-bearing on the knee joints helps the cartilage; this is especially true of cycling on flat surfaces or those with low to moderate step resistance.

Gymnastics: good if the relevant exercises strengthen weak muscles and stretch shortened ones. Exercises in a lying and sitting position take the load off the knee.

Hiking/mountain walking: same as with walking. Caution with constant ascending slopes. It is essential to avoid extreme mountain descents, such as 1,000 meters at a time.

Cross-country skiing: if the technique is correctly mastered, cross-country skiing is very suitable, because the joints are always stressed and de-stressed alternately. Strength, endurance, and the stability of the axes of the legs are encouraged.

Conversely, these sports can cause damage to the knee:

- Football/handball: Stresses caused by jumping high in the air increase the risk of sprains or falls; many turning, forward sprinting, and stopping movements

- Badminton/squash: Rapid stop-go movements in a very confined space increase the risk of sprains, twisting the knee or falling

- Weightlifting: Very heavy weights and the strongly flexed position of the knee when lifting place excessive pressure on the knee joints

- Alpine ski/snowboarding: Rapid travel and abrupt stops place extreme stress on the joints.

- Horse riding: Mounting and dismounting, including leaping on and off a horse, are associated with a strongly flexed position and great pressure on the knee joints. Also, there is always the risk of falls.

Editor's note: This article is an edited version of a translation of a report that originally published in German in the May 2014 edition of "Medizin mit Durchblick," the patient magazine of the DRG, the German Radiological Society. Translation by Syntacta Translation & Interpreting.