Where? That's the biggest question facing a veterinary surgeon when dealing with an injury in a performance horse, members of the British Medical Ultrasound Society (BMUS) heard at a special Olympics session during last week's annual meeting in Telford.

Equine vet Dr. Sarah Boys-Smith pointed out the key differences between human and veterinary practitioners is the way that ultrasound is used in diagnosing, treating, and monitoring athletic injuries in their patients. As a partner in Rossdales -- a leading veterinary practice in Newmarket, the home of the U.K. thoroughbred racing industry -- she was also part of the team looking after the health and welfare of horses competing in the equine events at the Olympic and Paralympic Games at London 2012.

Sarah Boys-Smith helped look after the health and welfare of horses competing in the equine events at the 2012 Summer Olympics in London.

Sarah Boys-Smith helped look after the health and welfare of horses competing in the equine events at the 2012 Summer Olympics in London.

Not surprisingly, the inability of her patients to communicate the nature of their injuries presents a significant hurdle to those efforts.

"Usually when we see our patients, it is in the chronic stage of an injury, and so there aren't any of the acute signs like swelling or inflammation to give you an idea of the location of the lesion. The first step is to trot the horse on a lunge rein to assess the severity of the lameness," she said.

"We would then put a nerve block in the foot of the affected limb and trot them again to see if that makes any difference. If it doesn't, we put in another nerve block further up the limb and repeat until we can find the right region. It is only then that we can use radiography or ultrasound to pinpoint the actual lesion," she explained.

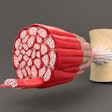

Another difference in the workload of veterinary practitioners treating sports injuries is that they are unlikely to see patients with muscle damage, which do occur but are generally left to heal naturally. In those cases that are seen, it will be a challenge to locate the lesion because the huge size of the horse's hindquarters and the limits on the penetration of the ultrasound beam. So almost all the injuries treated in performance horses affect the tendons or ligaments of its limbs.

Tendon damage is more common in horses competing in cross-country competitions, National Hunt (jump), or flat racing than in the general equine population.

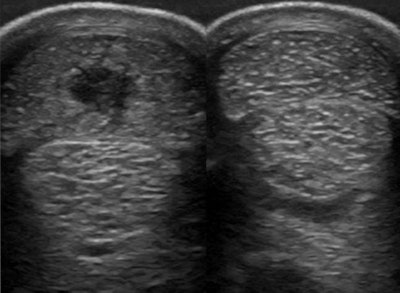

"Both high-speed work and jumping can put a critical load on the tendon structure," Boys-Smith commented. "Ultrasound is used to look for enlargement of the tendon, find lesions within the tendon, and identify any loss or disruption of the fiber pattern within the tissue."

Often, the treatment consists simply of box rest and a gradual exercise program once there is evidence of healing. However, ultrasound also is used by equine veterinarians for treatment, particularly in guiding the needles used to administer stem cell therapy, which has proved to be the only effective form of active treatment for equine tendon damage.

Superficial digital flexor tendon injury; abnormal tendon on the left, normal tendon on the right. Image courtesy of Sarah Boys-Smith.

Superficial digital flexor tendon injury; abnormal tendon on the left, normal tendon on the right. Image courtesy of Sarah Boys-Smith.Injuries can also occur in horses competing in more sedate sports.

"Damage to the suspensory ligament is quite a common finding in dressage horses," Boys-Smith noted. "This is the ligament that attaches to the back of the cannon bone in the knee of the horse's fore limb and the hock in its hind limb. It runs downs into the sesamoid bones of the foot and is there to prevent excessive extension of the fetlock joint. The injuries can happen as a result of the high stepping gait used during a dressage event."

While their caseload may differ, the equipment used by a veterinary radiologist will be very familiar to a practitioner dealing with human patients.

"All the equipment that we use was originally developed for the human medical market. We will use a standard 3- to 5-MHz probes for some investigations and 10- to 12-MHz probes for tendons. We also use linear, convex, and microconvex probes in different examinations, but they are the much the same as those used in human medicine," she concluded.