Ultrasound still has a leading role to play in sports imaging, particularly because ultrasound-guided intervention enables injured athletes to return to the field of play quickly, attendees at the British Medical Ultrasound Society (BMUS) annual conference learned last week in Telford.

The success of the Olympic polyclinic at London 2012 was due in part to the groundwork and experience of the Olympic Medical Institute (OMI), which was founded 10 years ago at Northwick Park Hospital, London, according to Dr. Denis Remedios, a consultant radiologist at Northwick Park who was a volunteer at the summer games.

Details of an important study conducted at the OMI were presented at the BMUS conference and conducted by Dr. Tina Mistry and Dr. Leanne Singh, who work alongside Remedios at Northwick Park. Of the 56 track and field event athletes who attended the OMI between March 2007 and January 2010, and who received ultrasound-guided intervention, the majority were due to lower limb injuries including Achilles and ankle injuries. Most common injuries were paratendinitis/tendinitis (55%), bursa/bursitis (14%), muscle tears (11%), stress fractures (7%), tenosynovitis/capsulitis (4%), and others such as ganglion and neovascularity (9%).

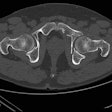

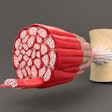

Ultrasound shows thickening of the left Achilles tendon in a 34-year-old man who is a triathlete. Neovascularity is in keeping with Achilles tendonitis. Image courtesy of Dr. Denis Remedios.

Ultrasound shows thickening of the left Achilles tendon in a 34-year-old man who is a triathlete. Neovascularity is in keeping with Achilles tendonitis. Image courtesy of Dr. Denis Remedios.The aim of the study was to determine the ability of ultrasound-guided intervention to reduce recovery time and return to field of play. Patients were divided into groups composing those who received ultrasound scans without further intervention, and those who received ultrasound scan with intervention, such as steroid injection therapy or paratenon stripping. Time to return to sport, types of injuries, and outcomes in terms of medals won were the primary study endpoints.

"Of the 34 athletes who received scans without intervention, 14 won medals after having been rehabilitated appropriately. The average recovery time for these athletes was 11.3 months," Remedios reported.

For those 22 athletes who did receive intervention through injection therapy or needling, recovery time to field of play was 4.6 months. "This was considerably faster and probably significant, despite numbers being small. It is always difficult to recruit a large series of elite athletes, of which there are very few," he commented.

Of those who received ultrasound-guided intervention, they returned to the field of play more quickly than the other group, yet only two won international medals. Remedios explained that the athletes who received interventions were those with the most severe injuries or more chronic injuries who had the greatest challenge to return to competitive form.

"I think return to the field of play is the better outcome measure," he said. "Ultimately ultrasound-guided therapy means we can get patients back to the field of play faster."

Remedios also highlighted other conclusions that chimed with previous findings suggesting that the success of injection therapy was improved if clinical and imaging diagnosis showed good correlation. This happens when there are excellent sports physicians whose clinical diagnosis is concordant with the imaging, he explained.

Previous work presented at the 2008 European Society of Musculoskeletal Radiology (ESSR) - 15th Annual ESSR/BSSR Meeting showed that in situations where concordance existed, there was a 94% chance of successful injection therapy.

"Mechanisms of referral are important here, in particular when the treatment is guided by immediate discussion at the time of imaging. With these elite athletes, a case conference at the actual time of imaging enables best treatment," Remedios pointed out, who led the previous study.

During London 2012, radiologists encouraged the athletes' physicians or physiotherapists to accompany their patients to the polyclinic for imaging. This meant we arrived at a better final diagnosis and tailored their rehabilitation more appropriately, he said.

"If you're looking for imaging appropriateness and radiation safety, then London 2012 ticked all the boxes," Remedios said, adding that all procedures were justified and performed for appropriate reasons. "After four years of planning, it actually felt like it was all worthwhile."

Looking ahead to the Rio Games in 2016, Remedios noted that using radiologists with specialist experience in sports imaging, especially with elite athletes, had been a definite bonus in London. He added that attention should be given to the quality of equipment and drugs used, and reports often relating to very sensitive cases should be double-checked to ensure correctness of diagnosis and correctness of messages conveyed.

Ultimately, the success of the imaging service at London 2012 demonstrated what was possible with adequate funding. "If it was translated to the National Health Service, we worked out that it would cost 11 times what the current NHS costs. The expertise is available, but it's the money that talks," he concluded.