Imaging has an important role to play during pregnancy, and in many cases the risks are manageable and negligible compared with the potential dangers of not imaging. Furthermore, examinations of the extremities, head and chest are not restricted, according to Dr. Peter Vock, a professor in the department of diagnostic radiology at Bern University Hospital.

Research shows there can be a lack of knowledge among physicians about how to treat pregnant women. In addition, pregnant women tend to feel more anxious than nonpregnant women about any examination, and delays can occur in their care. This puts an emphasis on the need for accurate and balanced patient information, reliable consent procedures, good documentation, and appropriate education and training methods for staff, noted Vock, a speaker at the ECR refresher course on diagnostic radiology and pregnancy.

A critical factor is the justification for a specific examination. He breaks down procedures into four categories: those involving low exposure (x-rays of extremities, head, and chest); those examining the trunk of the body, without direct radiation to the uterus; those involving direct radiation to the uterus; and nuclear medicine examinations. Justification depends on the stage of pregnancy, and of particular importance are organogenesis (mainly three to 15 weeks postconception), and the size and position of the fetus.

Patient consent is necessary whenever fetal dose is above 1 mGy. The simple rule is that pregnancy status must be established when the uterus is in direct contact with the x-ray beam, but no hospital's policy can guarantee a 100% detection of pregnancy. Research suggests that around 2.9% of trauma patients are pregnant, and 0.3% to 1% of women do not know they are pregnant. In those under the age of 18, it is essential to seek a balance between the patient's right to privacy and the parents' rights, Vock explained.

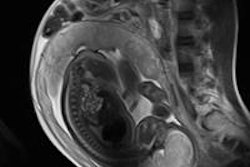

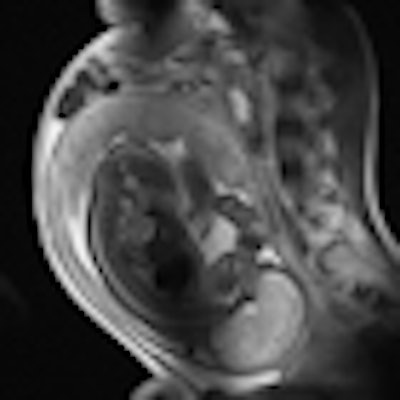

Fetal MR spectroscopy can assist with in utero measurements of fetal cerebral lactate concentrations. It may provide information on the adequacy of fetal oxygenation, and can help with decision-making on the optimal time of delivery. This figure shows fetal localizers used for spectroscopy measurements. Image courtesy of Janet De Wilde, PhD, and C. McComb.

Fetal MR spectroscopy can assist with in utero measurements of fetal cerebral lactate concentrations. It may provide information on the adequacy of fetal oxygenation, and can help with decision-making on the optimal time of delivery. This figure shows fetal localizers used for spectroscopy measurements. Image courtesy of Janet De Wilde, PhD, and C. McComb."In the pre-examination questionnaire for determination of pregnancy, it is important to ask two questions: What was the first day of your last complete menstrual period? To the best of your knowledge, are you pregnant, or do you think you could be?" he said during last year's ECR refresher course on pregnancy.

In the early stage (< menstrual day 28/35), a urine test is not useful in ruling out pregnancy because of the sensitivity threshold (25 mIU/mL HCG). A lab test is more sensitive but is time-consuming. This test may be useful, but does not replace a proper direct inquiry, pointed out Vock. For higher exposure examinations that involve imaging the trunk of the body with direct radiation to the uterus, pelvic fluoroscopy (20-100 mGy), and pelvic CT (single phase < 50 mGy), the examination should be postponed unless there is a serious need, in which case the radiologist should plan or adapt the examination. Always get consent and document your actions, he advised.

To optimize an examination, he recommends avoiding direct radiation to the uterus, getting as few radiographs as possible, keeping fluoroscopy examinations short, and using collimation. In CT, it is important to use a single abdominal pass, low CT dose index (CTDI ), low kVp, and to avoid the uterus. Also, think about protocols in clinical situations such as pulmonary embolism, appendicitis, and urinary stones, and consider documentation and quality control.

In MRI, fast sequences are used to overcome image quality artifacts caused by fetal motion, and this can lead to the use of high-specification magnetic field gradients; the frequency range for the gradients is from 1 kHz to 10 kHz. The main concerns are the clinical effects of low-frequency EMF (electromagnetic fields)-induced currents and acoustic noise, but overall there is no indication the use of clinical MR procedures during pregnancy produces adverse effects, according to Janet De Wilde, PhD, executive manager of SINAPSE (Scottish Imaging Network: A Platform for Scientific Excellence) at the University of Edinburgh.

|

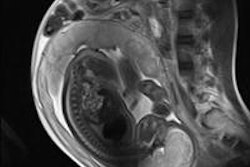

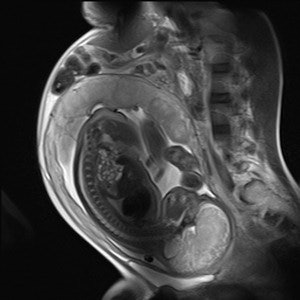

| Sagittal HASTE image used for planning further fetal images in other planes, taken at the Clinical Research Imaging Center, University of Edinburgh. Image courtesy of Janet De Wilde, PhD, and Dr. Scott Semple. |

Her tips are to avoid scanning above the normal controlled limit; if scanning in the first controlled level, then apply high specific absorption rate (SAR) sequences for as short a time as possible; high SAR sequences should be interspersed with low SAR sequences; and if the fetus or maternal abdomen are not the target organs of interest, then the fetus should be kept out of the transmit field of the radiofrequency coil, if possible. Particular care must be taken when scanning fetuses with poor placental function (e.g., in fetal growth restriction), and maternal heat stress has been reported to reduce placental perfusion.

"Care should also be taken when scanning pregnant women with conditions leading to impaired thermoregulation," she said. "Do not scan pregnant women who are febrile. The mother's heat loss pathways should be optimal, with no blankets, good bore air flow, and a reasonable room temperature."

Finally, she reiterated the advice of the Safety Committee of the Society of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. First, MRI is indicated for pregnant women if other nonionizing diagnostic imaging is inadequate or exposure to ionizing radiation is required. Second, no adverse effects on fetal growth or development have been reported to date. Third, the biological effects of MRI are still uncertain during pregnancy. Fourth, the use of MRI should be limited in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy at a specific absorption rate of less than 3 W/kg. Fifth, gadolinium-based contrast media are not recommended because they cross the placenta and enter the fetal circulation within seconds after intravenous injection.

Originally published in ECR Today March 5, 2011.

Copyright © 2011 European Society of Radiology