When a facial abnormality is suspected on routine prenatal ultrasound, fetal MRI can provide valuable clinical information, particularly about the secondary palate, and help evaluate other fetal abnormalities, award-winning research has shown.

"Knowledge of the developing fetal anatomy and recognition of the differing types of orofacial clefts on fetal MRI are important for enabling preoperative multidisciplinary treatment planning and parental counseling," noted Dr. Adeline Lo, a radiologist at Auckland Hospital in New Zealand, along with fellow presenters Drs. Peter Brugger and Daniela Prayer from Vienna.

Orofacial clefts, such as cleft lip, cleft lip and palate, or cleft palate alone, are one of the most common congenital craniofacial anomalies, affecting about 1 out of every 700 live births. They occur early in gestation, and may be due to maternal smoking or genetic factors, given the association of facial clefts to more than 200 genetic syndromes and higher concordance rates in monozygotic twins, noted the researchers, whose e-poster received a certificate of merit at ECR 2015.

Fetal MRI has many benefits, and is an excellent adjunct to ultrasound in the case of a sonographically detected orofacial abnormality, according to Lo, Brugger, and Prayer. But it is important to identify features on fetal MRI for the various types of facial clefts and to understand the formation behind the anatomical structures involved in the developing face of the fetus.

Orofacial clefts are sited unilaterally (64%), bilaterally (34%), or medially (2%), with differing and distinct radiological appearances, they explained. The primary palate is defined as structures anterior to the incisive foramen such as the alveolus and lip, while the secondary palate is composed of structures posterior to the incisive foramen, including the hard and soft palate.

Sole involvement of the lip occurs in about one-third of cases, and more frequently both the lip and palate are involved. Sole involvement of the secondary palate is less common, at around 1 out of every 2,500 live births, and there is a male predominance.

Surgical correction and prognosis is excellent for an isolated cleft lip, but repair difficulty rises with cleft complexity, such as the laterality of cleft and extent of posterior extension. Up to 21% of patients with orofacial clefts may also have one or more additional malformations like cardiovascular or skeletal abnormalities.

"A good understanding of the development and anatomy of orofacial clefts enables a more comprehensive radiological assessment in conjunction with adequate knowledge of the differing main types of orofacial clefts that may be encountered," the authors stated.

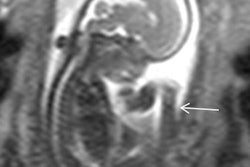

The normal fetal palate in the sagittal plane extends from the frenulum anteriorly at the upper lip as a continuous thin and linear hypodense structure, ending at the soft palate, which parallels the contour of the tongue to the level of the nasopharynx. The primary palate lies anteriorly and should blend seamlessly with the secondary palate, which is centered above the tongue. The incisive foramen is not identifiable on fetal MRI. The palate divides the nasal from the oral cavity and is best seen when surrounded by adjacent high T2-signal amniotic fluid.

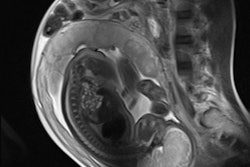

On coronal T2-weighted images, the palate forms a continuous upward arch paralleling the expected contour of the tongue surface and a midline perpendicular intersection with the cartilaginous fetal nasal septum, they continued. More anteriorly, the upper and lower lips can be seen as a continuous ring of soft tissue.

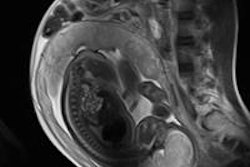

On axial T2-weighted images, the overlying facial soft tissues should be uninterrupted at the level of the maxilla/alveolar ridge. The underlying horseshoe-shaped alveolar ridge contains hyperintense tooth buds, which should be bordered by an intact continuous low-signal border.

Evolution of fetal MRI

Since the 1980s, fetal MRI has come a long way in the evaluation of complex fetal abnormalities, predominantly due to the development of ultrafast MR-sequences resulting in a reduction of fetal movement artifacts.

"Fetal MR is particularly suited to assessing fetal abnormalities discovered on routine sonography given the secondary palate is difficult to visualize on ultrasound due to bone shadowing artifact or the subjacent fetal tongue," wrote the authors. "Difficulties on ultrasound with patient body habitus, fetal lie, or evaluation in severe oligohydramnios can be also minimized with MR. T2-weighted, ultrafast spin-echo sequences, echoplanar sequences, and steady-state free-precession sequences with 2 to 4-mm slice thickness are obtained with the highest resolution possible, and the fetal lips and palate examined in axial, coronal, and sagittal planes."

Usually, anomalies are classified due to their pathogenesis or anatomical relationships. In relation to the cleft lip, alveolus, and palatal region, the following international classification has been established:

- Clefts of the anterior (primary) palate: lip, alveolus, lip, and alveolus

- Clefts of both primary and secondary palates: lip, alveolus, and hard palate

- Clefts of the secondary palate alone: hard palate, soft palate, hard palate, with soft-palate extension

Further subdivision into unilateral, bilateral or midline, partial, or total can be applied. With unilateral clefts of the primary and secondary palates, the disruption of facial symmetry can cause the cartilaginous nasal septum to be characteristically deviated. With bilateral defects, there may be focal protrusion of the central segment between the clefts, producing a distinctive premaxillary protrusion, they reported.

In the case of clefts of the anterior (primary) palate, the disruption is sited at the lip alone, the alveolar ridge, or both, and involvement can be unilateral or bilateral. This region of the alveolus is osseous with associated teeth buds. A cleft involving this area may be picked up on routine antenatal sonographic screening, but further assessment posteriorly of the secondary palate requires MRI, given the artifacts from bone shadowing and the adjacent tongue.

A cleft lip is seen as a focal disruption of the expected curvilinear contour of the upper lip, best seen on axial and coronal MR acquisitions, the researchers noted. With extension into the alveolar ridge, there is disruption and absence of the associated tooth buds and possible distortion of the nose and septum. With bilateral clefts, a characteristic protrusion of the central soft tissues or premaxillary segment is seen -- a so-called maxillary pseudomass sign.

For clefts involving the secondary palate, the disruption is sited in the posterior palate, consisting of both the hard and soft palates. Anatomically, this is defined as posterior to the incisive foramen and begins behind the third upper teeth.

Involvement can be unilateral or bilateral and can also involve the primary palate as a full-length defect, they stated. A cleft involving this area cannot be visualized on ultrasound but can be assessed on fetal MR as loss of the expected hypodense stripe on T2-weighted imaging. Hence, an open communication now lies between the nasopharyx and oropharynx, which can cause a superior bulge of the tongue into the gap. With bilateral involvement, the central protruding premaxillary segment can again be seen, they concluded.