Neither doctors nor patients are safe from error, which may be defined as an unintended act (either of omission or commission), or one that does not achieve its intended outcome.1 It is only in recent years, however, that the high error rate within medicine has been appreciated and there are now increasing efforts at prevention.

Most errors do not lead to patient injury as they are often intercepted. This can lead to a lack of awareness, and coupled with the difficulties in dealing with human error when it does result in harm has tended to deflect away from efforts at error prevention. Failure to deal with the factors that have contributed to the error or near miss allows them to remain in the system as "latent errors." This results in a residual risk as they may then combine with human fallibilities of mood, inattention, carelessness, and forgetfulness and cause a serious error.

Dr. Paul A. Spencer is chair of the READ project, and a consultant radiologist at the Rotherham NHS Foundation Trust, South Yorkshire, U.K.

Dr. Paul A. Spencer is chair of the READ project, and a consultant radiologist at the Rotherham NHS Foundation Trust, South Yorkshire, U.K.

Over the last decade, there has been a greater understanding that errors are often evidence of system flaws and although individuals will always be accountable for their actions, there has been a move away from the belief that mistakes demonstrate personal and professional failure. The publication of the U.K. National Health Service (NHS) report titled "An organisation with a memory"2 and in the U.S. the Institute of Medicine and National Academy of Sciences' report "To Err Is Human"3 have both helped.

At the end of this article, the case report about a stroke patient, reproduced from a recent newsletter of the U.K. Royal College of Radiologists (RCR), perfectly illustrates the type of observational error that can occur easily in clinical practice.

We all make mistakes, but perhaps the biggest mistake we could make is not to learn from them. It is our responsibility to recognize them, discuss them, learn from them, develop prevention strategies, implement these strategies, and finally test them for effectiveness. A great deal has been learned about how to design work environments to minimize the occurrence of errors and their consequences -- much of this from the aviation industry. Safety has to be institutionalized. We need to build in an acceptance that error does not mean negligence, and individuals need to be free of the fear of embarrassment by colleagues, patient reaction, or litigation.

Shared learning can help bring an objective evaluation of what went wrong, along with support from colleagues and sometimes patients.

In the U.K., the RCR has commissioned a project to develop a system of shared learning for the further education of members and fellows and the enhanced safety of patients.

Two fundamentally different systems were considered. The options were to setup a formal database or develop a confidential online reporting system. Both rely on the active submission of error events and discrepancies from radiologists. A database would allow a root cause analysis of events which can provide a robust learning opportunity, but there are significant challenges.

Meaningful information from all incidents/errors will need to be captured and inputting of the facts has to be agreed upon, structured, and accurate. Populating and analyzing the database would be time consuming, and clinical outcomes may not be available immediately. Also a database identifies trends which inform the organization rather than the individual. These problems are compounded by the absence of a secure reporting culture.

An online reporting system was considered achievable with a low-cost setup and management. Confidentiality and security are required to encourage reporting of incidents and READ (Radiology Events and Discrepancies) has been structured as a confidential, educational resource to encourage learning from events and discrepancies with the main aim of promoting improved patient safety.

The READ submission form is accessible online via the RCR website, and radiologists are encouraged to submit reports and safety related events that have occurred in their practice, whether in the NHS or the independent sector. These may be diagnostic or interventional events, technical or maintenance failures, regulatory or procedural aspects, or unsafe practices/protocols. The submitted report must be anonymized, and the reporter's identity is kept confidential.

All reports are reviewed by the READ panel and any learning points identified. In order to further ensure patient confidentiality the event is "disidentified" by changing age and sex along with alterations in some aspects of the event. In this way, a story is created based on a real event which can be published for shared learning.

For each case, we add a "lessons learned" commentary and endeavor to provide references for further reading. The narrative style provides a rich source for learning as much of us will relate to the familiarity of the environment within which they occur. Once published, all material relating to the case is destroyed.

READ is not an alternative to the local discrepancy meeting or incident reporting requirement. Discrepancy meetings are an established part of all radiology departments and provide an opportunity for individual reflection as well as group learning. The open reporting system utilized by the aviation industry has resulted in significant improvements in safety, and READ provides a similar opportunity to report all error events, as useful lessons may often be learned from incidents/discrepancies that do not result in adverse consequences.

READ offers material that can be used in a revalidation portfolio. The college will award one category 1 CPD credit for each case published and one category 2 CPD credit for those who read cases.

Individuals can learn from the mistakes of others without having to experience them themselves, and by encouraging a reflective approach to these events, radiologists are encouraged to become keen critical observers at their own initiative maintaining the motivation to improve.

References

- Leape LL. Error in Medicine. JAMA. 1994;272(23):1851-1857.

- Department of Health. An organisation with a memory: Report of an expert group on learning from adverse events in the NHS. London: Stationery Office; 2000.

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2000.

Dr. Paul A. Spencer is chair of the READ project, and a consultant radiologist at the Rotherham NHS Foundation Trust, South Yorkshire, U.K.

The comments and observations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions of AuntMinnieEurope.com, nor should they be construed as an endorsement or admonishment of any particular vendor, analyst, industry consultant, or consulting group.

Case Report: When is a stroke not a stroke?

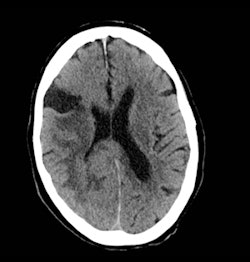

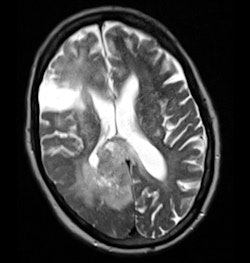

A 63-year-old person presented to the emergency department with facial asymmetry and mild left-sided weakness. After clinical assessment, the patient was referred to the stroke unit and a CT scan of the head was requested (figure 1). This was reported as showing ischemic changes within the white matter, with an area of established infarction in the region of the middle cerebral artery.

Following further clinical review, it was felt that the presentation was atypical for a cerebrovascular accident (CVA), particularly as the symptoms had been slowly progressive for two weeks. An MRI scan was requested. This demonstrated a large paracentral tumor in the right occipital lobe (figure 2). Review of the CT shows asymmetry of the gray white matter and compression of the ventricle which was not appreciated at the time of initial reporting.

Fig. 1 (left): Noncontrast CT scan of the brain. Fig. 2 (right): Axial T1 postcontrast scan.

Fig. 1 (left): Noncontrast CT scan of the brain. Fig. 2 (right): Axial T1 postcontrast scan.Reporter's comments

This is clearly an observational error. The referral direct from the stroke unit with clinical information suggesting a CVA may well have introduced a bias toward identifying the abnormalities as ischemic in origin.

Careful interrogation of the image, despite the clinical information, may well indicate causes other than "stroke."

Lessons learned

A "miss" occurs when an abnormality is visible but not seen at the time of reporting. Perceptual errors are related to psychophysiological factors including level of observer alertness, observer fatigue, duration of the observation task, and distracting factors that include the clinical information provided. Error can arise through "satisfaction of search" when the radiologist's attention is diverted to one radiographic abnormality which satisfies the "search for meaning" particularly if this correlates with the clinical information. This will result in a premature termination of search. Failures of abnormality detection are common to visual perceptual tasks in general and are relevant to other professions.1

Highlighting such an error every time we come across it reminds us of the importance of interrogating images in a systematic way and further develops a safety culture within radiology departments.

Reference

- Pinto A. Spectrum of diagnostic errors in radiology. World J Radiol. 2010;2(10):377-383.

This case originally appeared in the October 2012 edition of the READ (Radiology Events And Discrepancies) e-newsletter from the U.K. RCR. Reproduced with the permission of the RCR.