For radiologists, performing and evaluating resting-state functional MRI (fMRI) examinations will require education, availability of specific data treatment programs, and a sound understanding of the functioning of the brain in health and disease in order to make a correct decision about the patient's condition, according to a brain imaging expert in Belgium.

"To be useful in the clinic, I think we need a white paper about the chain -- indication, acquisition, postprocessing, and inference -- in order to set up large global studies," said Dr. Rik Achten, head of radiology at the University Hospital of Ghent. "If science finally proves resting-state fMRI (rsfMRI) is valuable, neuro-doctors will be sending their patients to radiology for such exams."

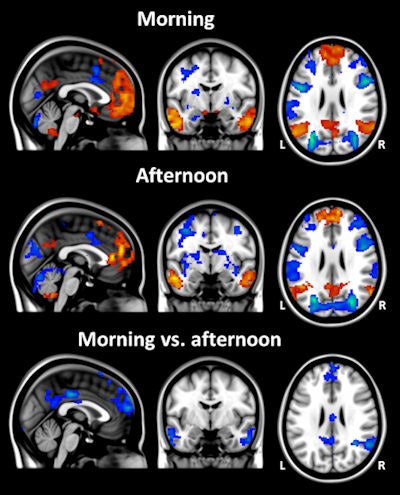

In the same group of subjects, the extent of resting-state activity differs between the morning and the afternoon. In a study conducted at KCL, half of the 16 subjects were scanned first in the morning and then in the afternoon, and the other half were scanned first in the afternoon and then in the morning. These average resting-state network maps show clear state-dependent differences in rsfMRI, which must be taken into consideration in future study designs. All images courtesy of Steve Williams, PhD.

In the same group of subjects, the extent of resting-state activity differs between the morning and the afternoon. In a study conducted at KCL, half of the 16 subjects were scanned first in the morning and then in the afternoon, and the other half were scanned first in the afternoon and then in the morning. These average resting-state network maps show clear state-dependent differences in rsfMRI, which must be taken into consideration in future study designs. All images courtesy of Steve Williams, PhD.The latest thinking on rsfMRI came under scrutiny during Friday's hot topic debate at the European Society for MR in Medicine and Biology (ESMRMB) congress in Toulouse, France, for which Achten was the session moderator. Experts participating in the debate addressed the current limitations of the technique versus its future potential.

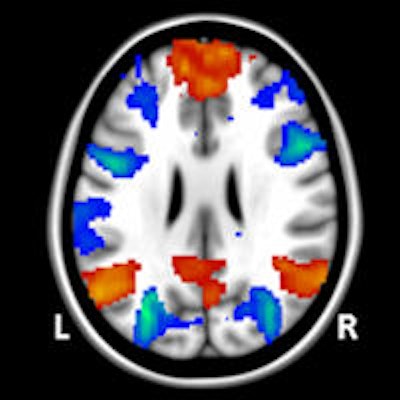

RsfMRI can be used to evaluate regional interactions that occur when a patient is not performing an explicit task. It works by observing changes in brain blood flow, which create a blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signal. Resting-state functional connectivity research has revealed a number of networks that are consistently found in healthy subjects and recognized through specific patterns of activity, and now researchers are using the technique to explore altered functional organization in neurological or psychiatric diseases.

In a precongress interview with AuntMinnieEurope.com, Achten underlined the importance of disentangling disease-related signals picked up from rsfMRI from those related to physiological variations before the technique can be clinically useful.

"It is not yet possible to see specific signals in individual patients pertaining to disease such as pre- and full Alzheimer's, and psychiatric diseases," Achten said. "What we want is a biological MR imaging marker to predict or diagnose disease, and evaluate it in terms of severity -- particularly in neurodegeneration and psychiatry -- as this would be important for treatment decisions. In addition, we want to predict and measure the behavior of the disease with therapy so that we know early on whether to continue or use an alternative type."

Its impact so far in the clinical setting has been minimal, but he is cautiously optimistic about rsfMRI, and like others involved in neuroimaging, he hopes for some tangible results over the next five years.

Because rsfMRI has the potential to become a key technique in brain imaging, MRI specialists are keen to understand the obstacles to routine use, and if, when, and how this technique could be applied to patient and treatment evaluation. In answer to the question "Is rsfMRI clinically relevant?" which was the title of the hot topic debate, the correct response is "not in isolation," according to Steve Williams, PhD, professor of imaging sciences and head of the neuroimaging department at King's College London (KCL). He warns that looking at brain activity data from rsfMRI was akin to listening only to the double bass section of the orchestra.

"The joke is that looking at the brain at 'rest,' we see Random Episodic Spontaneous Thoughts, these being uncontrollable in each individual patient, whereas task-related fMRI has a stricter and more controlled behavioral environment," he said. "When it comes to a cohesive observation, rsfMRI is easy to collect but very challenging to analyze and interpret."

Studying brain activity data from rsfMRI is like listening only to the double bass section of an orchestra, according to Steve Williams, PhD, from KCL.

Studying brain activity data from rsfMRI is like listening only to the double bass section of an orchestra, according to Steve Williams, PhD, from KCL.

Another drawback is the time required for building up a picture of brain activity with MRI, which can stretch over several minutes, with each whole brain image taking several seconds. Furthermore, current rsfMRI technology is focused on the measurement of blood oxygen, a proxy for "activity," rather than other more detailed markers.

"If we use electroencephalography (EEG), we can see electrical activity at a temporal resolution of milliseconds. We know that only a few percent of this electrical activity is visible on the timescale of current MRI, which limits our observation to long range, lower frequencies of approximately 1 Hz," Williams noted. "Therefore, rsfMRI only scratches the surface of obtainable brain information."

To make this functional test clinically useful, discrimination between patients and healthy subjects is necessary, but this would be challenging given the dramatic variation not only between subjects, but also within a subject during the course of the day.

"Circadian rhythm changes brain activity within individual patients so that even in a healthy subject scanned in the morning versus an afternoon, rsfMRI will yield significantly different results," he said. "For research purposes, scanning may have to be limited to the same time relative to waking up for each study subject."

All these issues need to be addressed before potential diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers for depression or Alzheimer's can be created. Furthermore, Williams raised the question of how such technology can be accurately validated when the results of some studies could be prone to subjectivity in terms of analytical methods and statistical thresholds.

"A recent thought-provoking paper highlighted how we can tease activity networks from the craziest of situations, a case in point being resting activity detected in a dead, frozen salmon!" he said.

Overall, he urges scientists to combine rsfMRI with other technologies and be mindful of its current limitations. "RsfMRI may have a huge future as it doesn't require standardized stimuli and so can be rolled out globally for larger scale studies," he said.

Fellow ESMRMB speaker and proponent of rsfMRI Dr. Martin Walter, who is a psychiatrist and neuroscientist, believes that its comparative ease makes the technique a potentially feasible means of detecting the mechanisms of disease and treatment response, particularly in psychiatric patients.

Walter, associate professor of psychiatry at Otto von Guericke University and head of the clinical affective neuroimaging laboratory, Leibniz Institute for Neurobiology in Magdeburg, Germany, admitted that specific prognostic and diagnostic imaging markers were lacking. Like Williams, he thinks rsfMRI should not be studied in isolation, but also is keen to highlight its advantages.

"Generally speaking, there is little insight as to how to treat individual patients who suffer from dementia or affective disorders such as depression," he commented. "However, there are hot spots in the brain that change physiology with depression. How they change can be predictive of what treatment is needed. RsfMRI is shown to be strongly predictive in studies testing accuracy in individuals because it can show changes that can't be seen in structural, or in other functional, assessments."

Furthermore, subgroups of patients need specific tailored treatment. Likewise, these subgroups remain difficult to diagnose.

"There are depressed patients who will respond well to first-line treatments and those that won't, and who will need more intensive pharmacological second-line treatment. If we can spare a patient three months of extraneous treatment by using the markers to go directly to the most appropriate therapy, this will be a serious achievement," Walter said. "The diagnostic accuracy and the predictive value for pharmaceutical decisions will be of great clinical benefit for affective disorders."

Next to improving methods for determining specific data in individual patients -- namely, understanding what these imaging markers looked like in each case -- the next step was for researchers to discuss with clinical colleagues and the MRI community what questions or indications would benefit from this functional test, he said.