A combination of contrast-enhanced mammography with ultrasound performs as well as breast MRI for preoperative staging for breast cancer, according to a Dutch study published on 2 August in the European Journal of Radiology.

The study findings suggest that an effective "one-stop-shop" imaging strategy is available to clinicians and their breast cancer patients, wrote a group led by first author Dr. Marc Lobbes, PhD, director of the breast imaging center of the Zuyderland Medical Center in Sittard-Geleen, the Netherlands.

"Breast MRI is hardly necessary when contrast-enhanced mammography in combination with ultrasound has been performed as a single appointment imaging strategy in breast cancer patients," wrote Lobbes, who is a member of the scientific counsel of the Dutch Expert Center for Screening and an educational board member of the European Society of Breast Imaging (EUSOBI).

Radiologists use preoperative imaging to assess the extent of disease in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer and to stage treatment, the group wrote. Contrast-enhanced mammography is a relatively new imaging method, introduced in 2011, and previous research has touted it as a way to increase the diagnostic accuracy of mammography, rivaling breast MRI. It has also been found to be at a lower cost than MRI.

Lobbes and colleagues conducted a literature review to assess the value of combining contrast-enhanced mammography with targeted ultrasound in a single appointment. They found that contrast-enhanced mammography performs equally well to MRI in measuring tumor sizes, with the sensitivity of both approaches being comparable in detecting breast cancer. However, mammography shows more specificity than breast MRI, which translates to slightly fewer false-positive findings in preoperative staging.

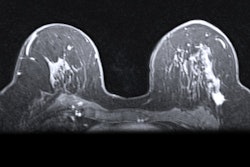

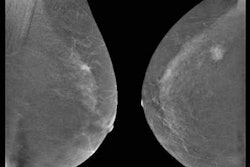

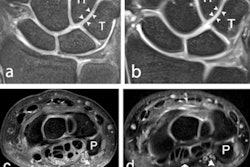

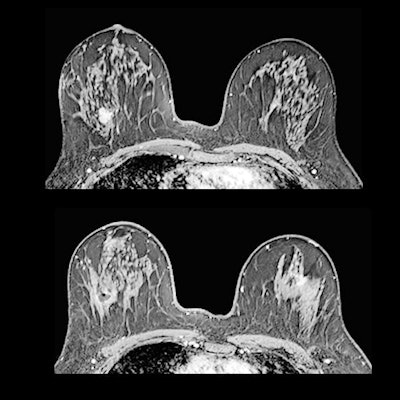

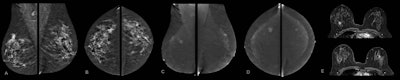

Contrast-enhanced mammography exam of both breasts in two views. In the first two low-energy images (A, B), an ill-defined mass can be seen in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast at the location of a palpable mass in a 52-year-old patient. In the left breast, no relevant abnormalities can be detected. In the recombined images (C, D) of a contrast-enhanced mammography examination, contrast uptake can be appreciated. The recombined images show an irregular enhancing mass in both breasts -- both in the upper outer quadrant. Tissue sampling revealed a bilateral invasive breast cancer of no special type. A breast MRI examination performed prior to surgery also confirmed the presence of two irregular enhancing masses on these contrast-enhanced T1 weighted images (E: top example is the cancer in the right breast; bottom example is the left breast). All images courtesy of Dr. Marc Lobbes, PhD.

The group also noted that axillary ultrasound can be performed during the same appointment as contrast-enhanced mammography and shows equal performance compared with evaluating the axilla on standard breast MRI.

A previous study found that breast MRI tended to slightly overestimate tumor size by about two millimeters on average, while contrast-enhanced mammography did not, the researchers noted. Other studies the team cited showed comparable accuracy between the two approaches.

Lobbes and colleagues also concluded based on previous research that no evidence exists to support supplemental breast MRI for more accurate appraisal of the axillary lymph nodes when ultrasound was already performed earlier.

One potential downside of combining contrast-enhanced mammography with ultrasound may be missing internal mammary lymph node metastases, since they are not in the field of view of any mammographic image, the group wrote. However, they also wrote that the consequences of "missing" these metastases by any kind of imaging modality are limited in terms of treatment and prognosis.

The only exceptions to consider breast MRI over other imaging methods for preoperative staging include patients with lobular cancer, breast implants, an allergy for iodinated contrast agents and renal insufficiency, or when breast lesions are not within the mammographic field of view, according to the investigators. In all other subgroups, clinicians can consider using contrast-enhanced mammography.

"When considering the combination of contrast-enhanced mammography and ultrasound as a single appointment imaging strategy for preoperative staging of breast cancer, there is only limited room for an additional benefit of breast MRI," the authors concluded.