With the assistance of diffusion-tensor MR imaging (DTI-MRI), researchers from Spain and Germany have found evidence that damage to the brain's white matter continues even after men who consume copious amounts of alcohol have stopped drinking, according to a study published online on 3 April in JAMA Psychiatry.

The findings indicate that microstructural changes still occur in white matter as late as six weeks into abstinence, which contradicts conventional wisdom that deterioration ends when the heavy drinking does. DTI revealed similar white-mater alterations in rats that were subjected to long-term alcohol consumption, also suggesting that this underlying degenerative process continues to evolve after the cessation of drinking.

"We found that at two and six weeks of abstinence, the microstructural changes progressed with further decrease of fractional anisotropy and increase of radial diffusivity in humans and rats," wrote first author Silvia De Santis, PhD, from the Institute of Neuroscience CSIC-UMH in Alicante, Spain, and colleagues. "These results challenge the conventional idea that the microstructural alterations start to revert to control values immediately after discontinuing alcohol consumption and provide insights into the neuroadaptations occurring during abstinence."

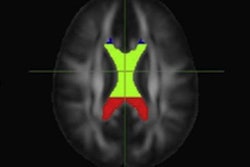

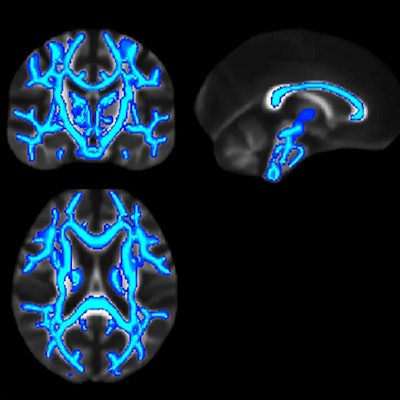

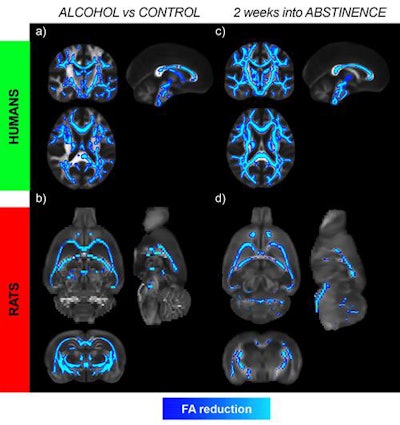

Microstructural changes in white matter in human alcoholics (a) and alcohol-exposed rats (b) were measured using DTI-MRI to provide an index of microstructural integrity. The changes further progress after two weeks of abstinence in both species, as seen in (c) the humans and (d) rats. The results challenge the current view that alterations in the brain begin to normalize immediately after quitting alcohol and indicate that persistent brain deficits can occur much earlier than is currently believed. Images courtesy of Silvia De Santis, PhD.

Microstructural changes in white matter in human alcoholics (a) and alcohol-exposed rats (b) were measured using DTI-MRI to provide an index of microstructural integrity. The changes further progress after two weeks of abstinence in both species, as seen in (c) the humans and (d) rats. The results challenge the current view that alterations in the brain begin to normalize immediately after quitting alcohol and indicate that persistent brain deficits can occur much earlier than is currently believed. Images courtesy of Silvia De Santis, PhD.There is no doubt about the harmful effects of alcohol, and the detection of alcohol-induced brain damage is a high priority. However, there are no reliable diagnostic markers to characterize brain damage due to alcohol, the researchers noted, especially at the beginning of abstinence -- a time when the chance of relapse to drinking is high.

For this study, De Santis and colleagues sought to determine specific patterns of alcohol-related brain changes through DTI in men with alcohol use disorder and in rats with similar consumption, and to monitor any brain changes in the first six weeks of abstinence. They enrolled 91 men with alcohol use disorder (mean age, 46.1 ± 9.6 years) who voluntarily underwent rehabilitation treatment in a German hospital, as well as 36 male controls (mean age, 41.7 ± 9.3 years). There were also 27 male rats in an alcohol group and nine male control rats.

The group conducted the human research in parallel with the examination of rats with a preference for alcohol to monitor the transition from normalcy to alcohol dependence in the brain -- a process that is not possible to see in humans, De Santis explained.

When the researchers reviewed the DTI results during the weeks of abstinence, they observed widespread microstructural abnormalities, such as reduced fractional anisotropy and axial diffusivity and increased mean and radial diffusivity, among men with alcohol use disorder, compared with the controls. The differences were most notable in the white-matter tracts of the corpus callosum and fornix/fimbria. That finding alone contradicts the conventional idea that the brain begins to return to normal function immediately after the start of abstinence.

Certainly, the results are rather surprising, added senior author Santiago Canals, PhD. "Until now, nobody could believe that in the absence of alcohol the damage in the brain would progress," he said in a statement from the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC).