After years in development, phase-contrast imaging is ready for clinical use, and one of its first functions could be to view the lungs of patients with a variety of pulmonary diseases, according to a German expert. The technology can highlight changes in the alveoli, which is uncharted territory for conventional x-ray.

"It's difficult to view very fine structures with traditional x-rays, and also those with very similar radiodensities," said Franz Pfeiffer, PhD, professor of biomedical physics at the Technical University of Munich (TUM), who received the Alfred Breit Prize at the Röntgen Lecture during last week's 98th German Radiology Congress (Deutscher Röntgenkongress, RöKo 2017) and Eighth Joint Congress of the German and Austrian Radiological Societies in Leipzig.

Chest x-rays and CT scans largely follow the same basic principle: different tissues absorb x-rays to differing degrees, and unabsorbed rays reach the film or digital detector to produce an image, he explained. Bones, for example, are highly radiopaque, and thus clearly distinguishable from the much more radiotransparent muscles and connective tissue that surround them. Not all tissues and body parts can be as well depicted as bones by traditional x-ray technology.

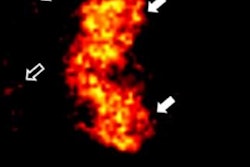

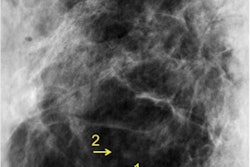

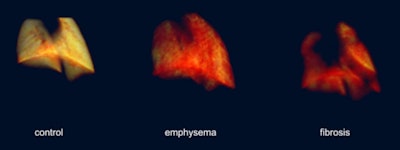

These images show the difference between a mouse control, emphysema, and fibrosis.

These images show the difference between a mouse control, emphysema, and fibrosis."Like light, x-rays can be interpreted both as particles and waves," Pfeiffer commented. "Traditional x-ray imaging uses particle absorption, exploiting the particle properties of the rays. In phase-contrast imaging, we use the wave properties."

Waves break up optically when they reach boundaries, in the same way as a prism, and can change direction and interfere with one another. "Until now, clinical imaging hasn't used all the properties of x-rays," he added.

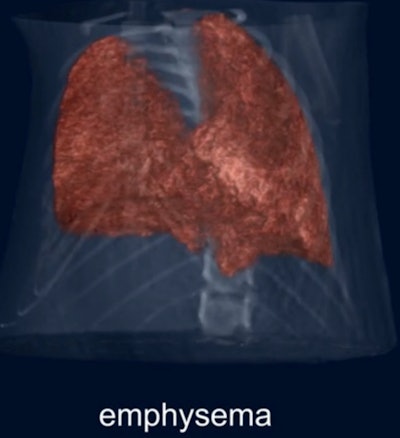

These images demonstrate phase-contrast on a mouse with emphysema (above) and fibrosis (below).

These images demonstrate phase-contrast on a mouse with emphysema (above) and fibrosis (below).Fine structure of the lungs becomes visible

This is now changing, as Pfeiffer's team and others around the world develop medical applications for phase-contrast imaging, previously used purely for research purposes. After thousands of experiments with disease models over many years, he and his colleagues Dr. Ernst Rummeny (at TUM) and Dr. Werner Jaschke, from Innsbruck, one of the moderators of the Leipzig conference, are taking the first steps to adapt the new method for human use.

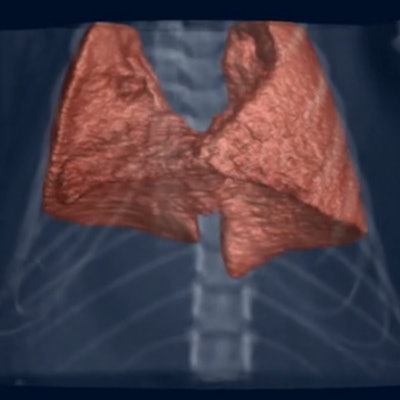

Pfeiffer thinks the technology has potentially huge benefits for pulmonary imaging. Traditional x-ray and CT are good at identifying larger tumors, but are of limited use when it comes to examining changes in the fine structure of the lungs.

"Phase-contrast imaging lets us see things right down to the alveolar level," he said. "For example, we can spot pathological changes caused by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at a very early stage. It's also very good at showing adhesions due to pulmonary fibrosis and radiotherapy."

Painstaking work

Franz Pfeiffer, PhD.

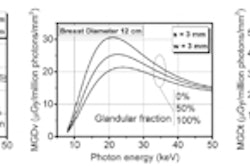

Franz Pfeiffer, PhD.Essentially, phase-contrast imaging involves the use of an additional filter for normal CT machines rather than being a device in its own right. Manufacturing such filters is a challenging task because they need to be extremely thin and fine-meshed to create the necessary wave effects.

"We need mesh elements around 10 µm wide and up to 300 µm high, like box lids standing very close together on their edges," Pfeiffer continued. "They're not easy to produce."

Until now, the meshes have been made of gold, but using other materials could make them much cheaper in the future. Many leading medical device manufacturers are currently working on solutions and building prototypes.

Editor's note: This is an edited version of a translation of an article published in German online by the German Radiological Society (DRG, Deutsche Röntgengesellschaft). Translation by Syntacta Translation & Interpreting. To read the original article, click here.