An x-ray imaging technique that can deliver breast cancer screening with comparable image quality to conventional mammography, but with an order of magnitude less dose, has been developed by a European collaboration. The optimized x-ray phase-contrast imaging (XPCI) technique was demonstrated using a synchrotron source, but is compatible with lab-based, polychromatic x-ray sources, making translation into the clinic feasible.

"Translating these extreme radiation dose reductions into clinical mammography would have great practical implications, as it would make mammography a much safer exam," said first author Paul Diemoz, PhD, research associate in the Department of Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering at University College London. The reductions could allow screening to be extended to younger women at high risk of breast cancer and enable more frequent imaging, enabling the earlier detection and treatment of tumors.

Paul Diemoz (left) and co-author Alessandro Olivo (right) from UCL, with an edge-illumination set up in the laboratory (not the synchrotron set-up used in the study).

Paul Diemoz (left) and co-author Alessandro Olivo (right) from UCL, with an edge-illumination set up in the laboratory (not the synchrotron set-up used in the study).Breast cancer screening is seen as one of the applications set to benefit most from XPCI. In principle, XPCI is a significantly more sensitive indicator of tissue morphology than conventional x-ray techniques that measure attenuation. Furthermore, because phase contrast does not require photon absorption by tissue, significantly higher energies can be used than in conventional radiography. Despite this, however, researchers have struggled to reduce image doses below current clinical levels. Researchers at UCL, the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, France, and Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich sought to overcome this with an optimized version of an existing XPCI technique.

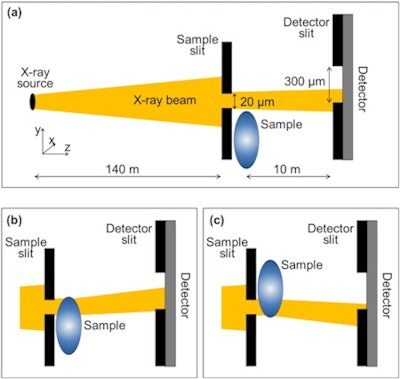

Edge-illumination XPCI has already been implemented using both the near-ideal beams provided by synchrotrons and lab-based, polychromatic x-ray sources. The technique exploits the refraction of x-rays by tissue. A manifestation of phase change, refraction varies the proportion of a finely collimated beam passing through slits in a mask placed in front of a detector. However, intensity also varies with absorption and to date, phase retrieval algorithms used for edge-illumination XPCI have required two or more images in different geometries to separate the two variables. The requirement makes it impractical for clinical use (Physics in Medicine and Biology, 21 Dec 2016, Vol. 61:24, pp. 8750-8761).

Edge-illumination XPCI measures change in x-ray phase by exploiting the refraction of an x-ray beam finely collimated using a sample mask. Refraction varies the proportion of the beam that passes through slits in a mask placed in front of a detector, creating contrast in the image.

Edge-illumination XPCI measures change in x-ray phase by exploiting the refraction of an x-ray beam finely collimated using a sample mask. Refraction varies the proportion of the beam that passes through slits in a mask placed in front of a detector, creating contrast in the image.The researchers eliminated the need with a new algorithm that exploits the near homogeneous composition of the breast. In such tissue, there is an approximate one-to-one correspondence between absorption and refraction coefficients. The approximation reduces phase retrieval to a single variable problem solvable with one image. "Since it requires just one input image, the single-shot method we developed in our work makes phase-contrast imaging compatible with fast and low-dose implementations," Diemoz explained.

In a further improvement, the researchers used a detector that introduces minimal noise and has near 100% efficiency at 60 keV, the photon energy used in their study. The MAXIPIX-CdTe detector was developed at the ESRF and combines thick 1-mm deep cadmium telluride crystals with single photon-counting readout chips.

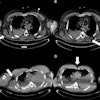

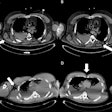

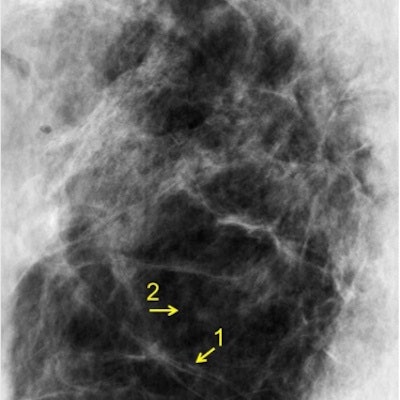

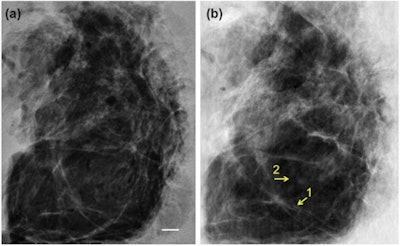

A 4-cm-thick breast tissue sample was imaged with conventional mammography (left) and using XPCI at the ESRF in Grenoble (right). The images show a similar level of detail, but corresponded to dramatically different mean glandular doses of 3.5 mGy and 0.12 mGy, respectively.

A 4-cm-thick breast tissue sample was imaged with conventional mammography (left) and using XPCI at the ESRF in Grenoble (right). The images show a similar level of detail, but corresponded to dramatically different mean glandular doses of 3.5 mGy and 0.12 mGy, respectively.The researchers tested their approach using the ID17 biomedical beamline at the ESRF, imaging 2- and 4-cm-thick tissue samples excised during routine mastectomies in two women. The mean glandular dose for each acquisition was 0.12 mGy, an order of magnitude smaller than a clinical mammogram, where the dose is typically 1 mGy to 1.5 mGy.

When the XPCI images were compared with those acquired with a conventional mammography set at 32 kVp and 221 mAs, the same tissue features, such as collagen strands and glandular tissue, were discernible. In the thinner sample, histological analysis independently confirmed the presence of those features. The corresponding mean glandular doses of the conventional mammograms, however, were some 30 times higher than the XPC images.

The researchers' next major goal is to translate the approach into a compact setup that can be used clinically. Several steps are needed, including investigations to identify a suitable x-ray source and filtration and an optimum system geometry. Larger masks that can cover a significant proportion of the breast are also needed; until now masks measuring only a few centimeters wide have been used. Each adaptation should be achievable with existing technology, Diemoz told medicalphysicsweb. "There is no basic limitation preventing them."