New research from Brazil has provided detailed information about the clinical, imaging, and electromyographic findings in babies with arthrogryposis associated with congenital Zika virus infection.

Tests to evaluate arthrogryposis were consistent with a neurogenic pattern, with electromyelographic findings and spinal MRI suggesting involvement of the lower motor neurons, according to lead author Dr. Vanessa van der Linden, a pediatric neurologist at Association for Assistance of Disabled Children (AACD) and Barão de Lucena Hospital in Recife, the Brazilian city at the center of the Zika epidemic. The pathophysiology of this condition might be related to the tropism of the virus by the upper and lower motor neurons, or to embryonic vascular change affecting these two segments.

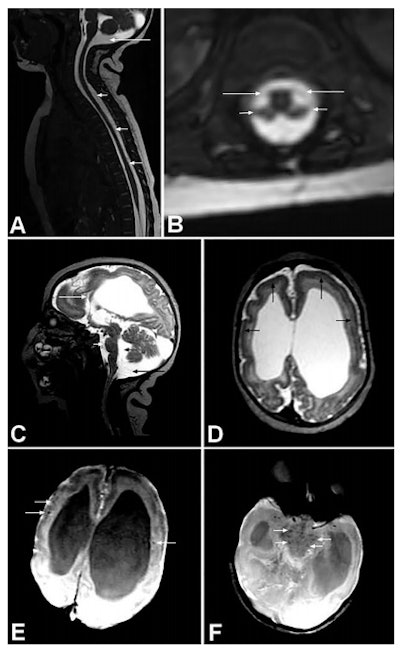

Spine and brain MRI of baby with arthrogryposis. A: Sagittal T2 weighted with fast imaging employing steady state acquisition (FIESTA) shows apparently reduced spinal cord thickness (short arrows) and mega cisterna magna (long arrow). B: Axial reconstruction of T2-weighted FIESTA shows reduction of medullary cone ventral roots (long arrows) compared with dorsal roots (short arrows). C: Sagittal T2-weighted image shows hypogenesis of corpus callosum (long white arrow), enlarged cisterna magna (long black arrow), enlarged fourth ventricle (short black arrow), and pons hypoplasia (short white arrow). D: Axial T2-weighted imaging shows pachygyria in frontal lobes (black arrows) and severe ventriculomegaly, mainly at posterior part of lateral ventricles. Axial susceptibility weighted image (E and F) show some hypointense, small dystrophic calcifications (white arrows) in junction between cortical and subcortical white matter (E) and in midbrain (F). All figures courtesy of the BMJ (2016;354:i3899, http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i3899).

Spine and brain MRI of baby with arthrogryposis. A: Sagittal T2 weighted with fast imaging employing steady state acquisition (FIESTA) shows apparently reduced spinal cord thickness (short arrows) and mega cisterna magna (long arrow). B: Axial reconstruction of T2-weighted FIESTA shows reduction of medullary cone ventral roots (long arrows) compared with dorsal roots (short arrows). C: Sagittal T2-weighted image shows hypogenesis of corpus callosum (long white arrow), enlarged cisterna magna (long black arrow), enlarged fourth ventricle (short black arrow), and pons hypoplasia (short white arrow). D: Axial T2-weighted imaging shows pachygyria in frontal lobes (black arrows) and severe ventriculomegaly, mainly at posterior part of lateral ventricles. Axial susceptibility weighted image (E and F) show some hypointense, small dystrophic calcifications (white arrows) in junction between cortical and subcortical white matter (E) and in midbrain (F). All figures courtesy of the BMJ (2016;354:i3899, http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i3899).Her group's article, published on 9 August by the BMJ, outlines the association between Zika virus infection in the womb and arthrogryposis, which causes joint deformities at birth, particularly in the arms and legs.

Microcephaly -- a rare birth defect where a baby is born with an abnormally small head -- and other severe fetal brain defects, are the main features of congenital Zika virus syndrome, but little is still known about other potential health problems that Zika virus infection during pregnancy may cause.

Until recently there were no reports of an association between congenital viral infection and arthrogryposis. After the outbreak of microcephaly in Brazil associated with the Zika virus, two reports suggested an association, but they did not describe the deformities in detail, so van der Linden and her colleagues decided to investigate the possible causes of the joint deformities.

In March 2016, 104 children were under evaluation at AACD for congenital infection presumably caused by the Zika virus. Only seven met the research team's inclusion criteria (brain imaging suggestive of congenital infection, a negative test result for congenital infections, and presence of arthrogryposis), two of whom were girls. All children tested negative for the five other main infectious causes of microcephaly: toxoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus, rubella, syphilis, and HIV.

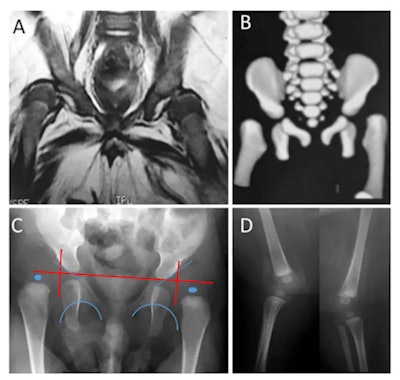

A: MRI shows bilateral dislocation of hips, epiphyseal core (small arrow), and dysplastic acetabulum (large arrow). B: 3D CT shows bilateral dislocation of hips. C: Anteroposterior radiographs show features compatible with dislocation of hips -- interruption of Shenton's arc, epiphysis hypoplastic proximal femoral acetabular index of 35°, and right and left proximal femoral epiphysis located laterally on side and bottom quadrant ombredanne. D: Radiograph shows subluxation of knee (arrows).

A: MRI shows bilateral dislocation of hips, epiphyseal core (small arrow), and dysplastic acetabulum (large arrow). B: 3D CT shows bilateral dislocation of hips. C: Anteroposterior radiographs show features compatible with dislocation of hips -- interruption of Shenton's arc, epiphysis hypoplastic proximal femoral acetabular index of 35°, and right and left proximal femoral epiphysis located laterally on side and bottom quadrant ombredanne. D: Radiograph shows subluxation of knee (arrows).The seven children underwent neurological and orthopedic examinations along with several other investigations: radiography, brain CT, or brain MRI without contrast, high-definition ultrasound of the joints (with specific attention to cartilage, synovia, pericapsular structures, and muscular tissue around joints), nerve conduction studies, and needle electromyography. If calcifications were present on brain imaging (CT or MRI), the researchers considered the possibility of congenital infections. Four children underwent MRI of the spine. MRI was not possible in two children as they were receiving mechanical ventilation on an intensive unit care.

All children showed signs of brain calcification. The theory is the Zika virus destroys brain cells, and forms lesions on which calcium is deposited. There was no evidence of joint abnormalities. This led van der Linden et al to note the arthrogryposis did not result from abnormalities of the joints themselves, but was likely to be of neurogenic origin, leading to fixed postures in the womb and consequently deformities.

Clinical pictures of children with arthrogryposis. A: contracture in flexion of knee. B: hyperextension of knee (knee dislocation). C: clubfeet. D: deformities in second, third, and fourth fingers. E: joint contractures in legs and arms, without involvement of trunk.

Clinical pictures of children with arthrogryposis. A: contracture in flexion of knee. B: hyperextension of knee (knee dislocation). C: clubfeet. D: deformities in second, third, and fourth fingers. E: joint contractures in legs and arms, without involvement of trunk.They point out further research is needed with a larger number of cases to study the neurological abnormalities behind arthrogryposis, but suggest that children should receive orthopedic follow-up because they could develop musculoskeletal deformities secondary to neurological impairment.

Based on these observations, the researchers conclude congenital Zika syndrome should be added to the differential diagnosis of congenital infections and arthrogryposis.

Because this is an observational study, no firm conclusions can be drawn about the effect of the Zika virus on arthrogryposis, but the authors suggest this condition might be related to the way motor neurons carry signals to the unborn baby's muscles, or to problems with arteries and veins (vascular disorders).

In May 2016, van der Linden was the subject of a lengthy profile article in Vogue. She was the first person to make the connection between the sudden surge in microcephalic babies and the mosquito-borne virus, according to the article. She has also featured in the Wall Street Journal.