If a 20-week fetal ultrasound scan reveals a potential brain abnormality, an MRI examination should be performed, U.K. researchers have recommended in an article published online by Lancet on 15 December.

The new prospective cohort study spanning 16 fetal medicine units has proved the addition of MRI exams provides increased certainty for parents whose midpregnancy ultrasound scan highlighted a potential problem, noted lead author Dr. Paul Griffiths, a professor of radiology at the University of Sheffield. Fetal brain abnormalities occur in about 3 in every 1,000 pregnancies, he added.

The study involved 570 women whose midpregnancy ultrasound scan revealed a possible fetal brain abnormality. Within two weeks of their first scan, they were given an extra scan using MRI, which increased the accuracy of the diagnosis, meaning the results of 93% of scans were correct. In comparison, the midpregnancy scan alone was correct in 68% of cases.

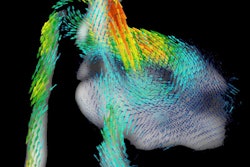

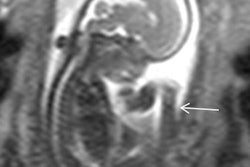

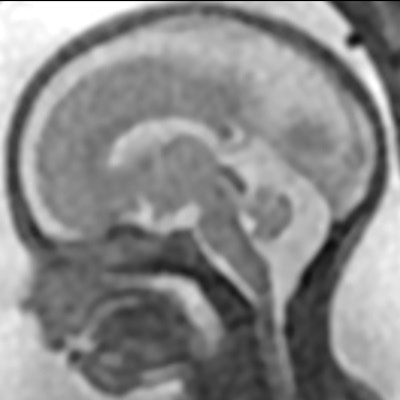

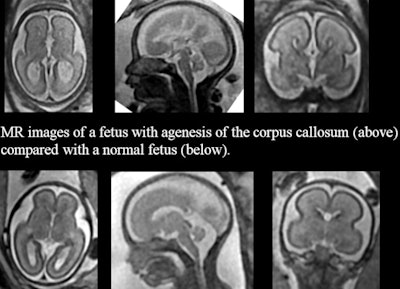

Fetal MR images of the normal brain compared with those showing an abnormality. Images courtesy of Cara Mooney.

Fetal MR images of the normal brain compared with those showing an abnormality. Images courtesy of Cara Mooney."When we initially proposed the study we anticipated an increase in diagnostic accuracy of around 10%, so when the results showed a 25% improvement overall, this was certainly higher than originally expected," explained Cara Mooney, study manager at the University of Sheffield's Clinical Trials Research Unit, in an email to AuntMinnieEurope.com. "The results also show a much higher than anticipated change in counseling and management than the 5% we had originally predicted."

The researchers recruited the participants between July 2011 and August 2014. They subdivided the cohort by gestation into two groups: one cohort of 18 weeks to less than 24 weeks gestation (n = 369), and another cohort of 24 weeks and older (n = 201).

Doctors analyzing the MRI and ultrasound scans were asked to rate how confident they were of their diagnosis. The researchers also looked at how the MRI result changed the prognosis and advice given by doctors.

The MRI gave extra information about the brain abnormality in half of cases (49%, 387 of 783). In one case, the MRI confirmed the ultrasound diagnosis and identified an additional abnormality. This information allowed doctors to give parents a more certain outlook, halving (55%) the number of cases in the "unknown" prognosis group and increasing the number of pregnancies predicted to be "normal" (135%), "favorable" (18%), or "poor" (56%), wrote Griffiths and colleagues.

Doctors agreed the extra MRI scan changed the outlook for the pregnancy in at least a fifth of cases (20%, 157 of 783). As a result, this changed how the pregnancy was managed in 1 in 3 cases (34%, 269 of 783), with terminations offered in an extra 11% of cases (84 of 783) after the MRI, and parents seeking counseling in 15% more cases (115 of 783).

Doctors using MRI were more confident of their diagnosis -- saying they had "high confidence" in 95% of cases (544 of 570), compared with 82% (465 of 570 cases) for doctors using ultrasound. In addition, 95% (257 of 270) of women said they would have an MRI scan if a future pregnancy showed a brain abnormality, and about 80% (227 of 277) said the information from the scan helped them better understand their baby's condition.

Overall, diagnostic accuracy was improved by 23% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 18-27) in the 18 weeks to less than 24 weeks group and 29% (CI: 23-36) in the 24 weeks and older group. Within the study, 2 fetuses out of 570 (less than 1%) were diagnosed correctly by the ultrasound and incorrectly by the MRI. Only cases identified by the ultrasound scan were given the extra MRI, so any cases in which an ultrasound did not identify an abnormality would not have been included in this study.

"Accurate diagnosis of significant brain abnormalities has important therapeutic implications. Consequently, it is essential that tools used for prenatal diagnosis are rigorously evaluated," wrote Dr. Rod Scott, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. Scott is a professor and the vice chair of the department of neurological sciences at the University of Vermont in the U.S., as well as a professor in pediatric neurology at University College London. "This trial strongly supports the view that [in-utero MRI] is an excellent technique, and it should be incorporated into clinical practice as soon as possible."

What's next?

Since the Lancet research was conducted, Griffiths and colleagues have been completing further analysis on the diagnostic confidence and have made some really interesting findings from the subgroup analysis, looking at specific brain abnormalities within the cohort, Mooney explained. The plan is to publish the results in early 2017, and further analysis will come from the qualitative substudy and health economics analysis, she said.

The team intends to follow up the children born from the cohort when they are 2 to 3 years old.

"This follow-up study will allow us to update our diagnostic accuracy data based on longer-term follow-up," Mooney pointed out. "We are also completing developmental assessments on the children to understand the effect that brain abnormalities detected antenatally mean for the child's prognosis and future development."

The authors' add-on study will involve recruiting women with a normal ultrasound scan to test the false-negative rate of ultrasound compared with MRI (i.e., the rate at which ultrasound missed a brain abnormality), she stated.

The Lancet study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment program. It was conducted by scientists from University of Sheffield, Newcastle University, University of Birmingham, Birmingham Women's Foundation Trust, and Leeds Teaching Hospitals National Health Service Trust.