A new pediatric study from Germany suggests that poorer children get more scans from radiation-bearing modalities like CT. Clinicians and radiologists need to be aware that children from deprived backgrounds may be more likely to undergo CT than their more privileged peers, the authors said.

This finding is important because recent studies have pointed to increased cancer risks associated with pediatric CT examinations, according to the group led by researchers from Leibniz Institute for Prevention Research and Epidemiology in Bremen. Lower socioeconomic status is associated with a higher trauma and chronic illness rate, so despite strict guidelines on CT use in children, they fear some less-experienced doctors may send children to CT before exploring other modalities.

Duty doctors should remain cautious when ordering and performing CT, as a child's economic background and living environment may play a significant part in how much radiation exposure they will incur during childhood, the researchers note in an article published online on 18 April in PLOS ONE.

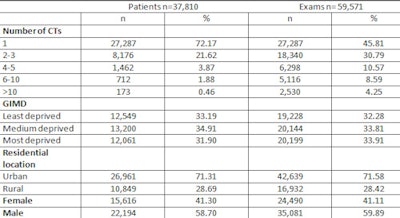

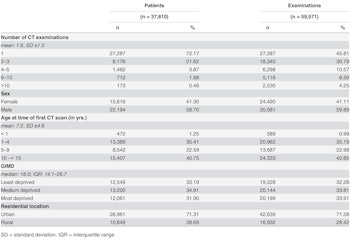

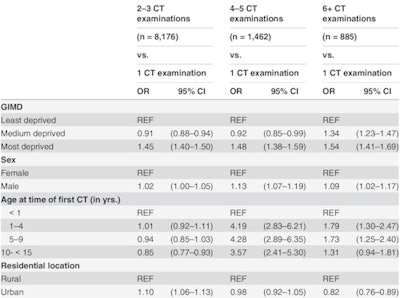

Factors associated with CT exams. All tables courtesy of Dreger et al, PLOS ONE doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0153644.

Factors associated with CT exams. All tables courtesy of Dreger et al, PLOS ONE doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0153644.The study covered the period 2001 to 2010, during which a total of 37,810 pediatric patients received 59,571 CT scans. Data were extracted from RIS for children under 15 without cancer who had at least one CT examination between 2001 and 2010 in 20 hospitals across Germany. Oncology-related scans were excluded, leaving scans for indications such as trauma, injuries, chronic diseases, or disabilities in the study.

The authors observed that increasing numbers of CT examinations in noncancer patients were significantly associated with higher regional deprivation, this based on the small-area German Index of Multiple Deprivation, which was used to assess regional deprivation. The deprivation scores were classified into least, medium, and most deprived areas and linked with the patient's last known postal code. The association of increased CT exams with higher regional deprivation also increased in the higher CT exams per child categories. Furthermore, male gender, higher age categories, and specific body regions were positively associated with increased numbers of CT exams.

The key findings were:

- The mean age at time of first CT examination was 7.2 years and the majority of children were males (58.7%). Overall, 35,081 CT examinations were conducted in 22,194 male patients and 24,490 CT scans in 15,616 female patients.

- Of the 37,810 patients, 27,287 (72%) patients received only one CT examination, while 885 (2.3%) patients received six or more CT scans. The mean number of CT scans was 1.58 (standard deviation: 1.48, range: 1-47).

- Most procedures were done in the oldest age group (10 < 15 years) (40.8%) and only about 1% of CTs were conducted in children younger than 12 months at time of first CT scan. Two-thirds of all CTs were recorded in children living in medium and most-deprived areas in Germany, and 71% of the study population lived in urban areas.

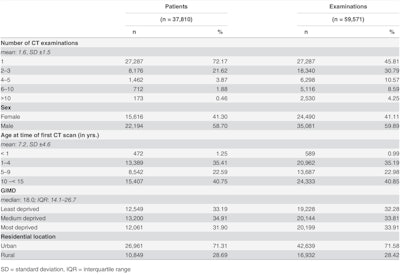

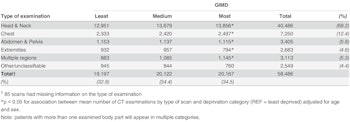

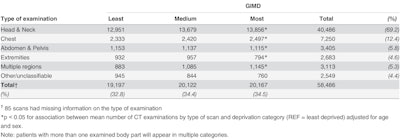

CT statistics.

CT examinations of the head and neck region accounted for the majority (69.2%) of all procedures during the study period, followed by chest examinations (12.4%). Overall, there was a statistically significant association between the number of CT examinations for each type of examination and deprivation status (p < 0.05). A positive association was observed in particular for examinations of the head and neck, chest, and multiple regions, with numbers of CT examinations increasing with higher deprivation status. These three examination types accounted for 86.9% of all examinations recorded during the study period.

Multiple CT exams.

Multiple CT exams.In Germany, CT examination rates increased from 0.08 to 0.12 examinations per individual on average annually between 1996 and 2010, while numbers of conventional x-ray examinations declined at the same time, according to the authors. These higher radiation doses are assumed to potentially increase children's risk for cancer, as children are known to be more radiation sensitive and have a longer lifespan after first exposure to potentially develop malignancies.

Recent studies on childhood cancer and exposure to medical ionizing radiation from CT examinations suggest the possibility of elevated cancer risks. Elevated risks for leukemia and brain cancer were observed in the U.K. while in Australia, a study has shown a higher incidence rate ratio for all cancers combined after CT exposure than for nonexposed individuals.

Type of CT exam.

A 2015 study published in Radiation and Environmental Biophysics and led by one of the paper's co-authors (Dr. Lucian Krille, Institute for Medical Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Informatics, University Medical Center Mainz), showed additional cancers were found in children who underwent CT in Germany.

"Among the 45,000 exposed children included in the cohort (of Krille et al), 1.8 CNS [central nervous system] tumors more than expected and five leukemia cases more than expected were observed. If one assumes a causal relation, this can be interpreted as about four additional CNS tumors and about 11 additional leukemia cases possibly associated with radiation exposure from CTs per 100,000 exposed children in Germany," said epidemiologist Dr. Hajo Zeeb, who is co-author of the latter paper and of this most recent study.

Dr. Hajo Zeeb

Dr. Hajo ZeebSeveral studies have shown that children from more-deprived areas in different regions of the world will undergo more CT exams than those from less-deprived areas, Australia being the exception where one study showed that children in higher socioeconomic status areas underwent more CT than those from areas of lower status, noted Steffen Dreger, medical geographer, epidemiologist, and lead author of the PLOS ONE article.

"Our work is closely related to other pediatric cancer risk studies from 2012 onwards across Australia, U.K., Taiwan, France, and Germany," he noted. "We wanted to see if socioeconomic status could be a confounding factor in pediatric cancers resulting from exposure to ionizing radiation."

The authors report that owing to conflicting results in the literature they did not know what to expect, but their own results were in line with those of the majority of their peers. They are aware of limitations to the study including a lack of knowledge about the indications leading to the examinations and the lack of detailed information on individual socioeconomic status of the families, which made using the deprivation index necessary.

Because most of the hospitals involved in the study were large university centers with similar equipment and infrastructure, they believe it is unlikely that unequal access to nonirradiating modalities played any role in the disparity of results in children from more deprived backgrounds and those from more privileged backgrounds.

Steffen Dreger

Steffen DregerInstead the authors pointed to the possible role of the frequency and type of trauma that children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds experienced, and also the type and incidence rate of noncancer diseases and pathologies. However, these reasons are speculative as these specific details were not researched. They also speculate about the role of negotiation power.

"Families in lower socioeconomic status areas tend to be less educated and less empowered to question authority figures such as doctors. Conversely, those from higher socioeconomic status areas may in some cases, have further knowledge about radiation risks from CT examinations and engage in further discussion with the treating physician in nonemergency situations, which might influence the type of exam ultimately requested by the physician, if warranted by the existing guidelines," Dreger said.

CT is the gold standard in many instances of trauma, but for nononcological pathologies, this might not be the case. In a separate site project with Japanese colleagues, the group researched what percentage of CT stemmed from trauma and what percentage of exams was related to other nonmalignant illness. Dreger said in one German medical center, over a period of two years, roughly 1,000 children were imaged with CT. For nononcology-related CT, 45% of exams were due to trauma, and the rest involved conditions such as deformity and postop follow-up.

Back in 2010 and 2011, the group researched CT risk awareness among hospital doctors and discovered knowledge gaps in certain aspects of associated cancer risk, as well as identifying that doctors desired more training and information in relation to guidelines.

"It is possible that more experienced emergency room doctors are more restrictive with CT use in children, but whether this plays a role in our current results is hard to tell," Zeeb said.

This latest paper is aimed at radiation epidemiologists and also at clinicians and radiologists involved in pediatric CT. It will be included in the IARC's Epi-CT study that aims to pool all pediatric CT study data in an ongoing strategy to limit and raise awareness of pediatric exposure to ionizing radiation in medical exams.

In a second step, Dreger et al are keen to conduct case control studies to look more closely at the medical history of patients including cancer predisposing factors in order to arrive at more precise risk estimates.

"We hope our work will encourage doctors to question whether CT is medically indicated in specific pediatric cases and that it will stimulate additional thinking around patients' socioeconomic status. This paper is another piece of the puzzle that we hope will generate more awareness and care taken over a sensitive part of the population," Dreger concluded.

Editor's note: The image on the home page is a whole-body CT scan of a patient with multiple trauma taken with a Revolution CT system. Image courtesy of GE Healthcare.