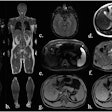

Undisturbed and unwrapped, a selection of the British Museum's extensive mummy collection has been imaged with the latest single- and dual-energy CT scanner technology. The results have afforded scientists and ancient historians a rare glimpse into the secret lives of everyday people who lived in Egypt and Sudan many millennia ago.

But members of the general public can share the spectacle of the scans too. Eight mummies and interactive CT images are available for viewing in an exhibition titled, "Ancient lives, new discoveries" that runs at the Museum in central London until 30 November 2014.

The exhibition is more about life than death, according to Dr. Daniel Antoine.

The exhibition is more about life than death, according to Dr. Daniel Antoine."The exhibition is more about life than death," explained Dr. Daniel Antoine, curator of physical anthropology at the British Museum. "We wanted our exhibition to investigate ancient lives. A lot of museums investigate death and the dead but we wanted people to realize that these remains belong to people who once lived along the Nile Valley and they just happen to be mummified."

He explained that the afterlife was highly respected and revered in ancient Egypt, and ancient Egyptians wanted to live forever. The physical embodiment of the dead in the form of a mummy helped them achieve this; contemporary society believed the dead person's spirit -- the ka that relied on the physical mummy to exist -- could leave the tomb and walk free.

Some of the mummies have been removed from the museum's rarely seen store of 80 Egyptian men, women, and children mummies, and 40 naturally preserved bodies from Sudan. They all date from 5,500 B.C. to the Christian period in Sudan at 700 A.D.

Rare and exquisite, the collection has benefited from the valuable foresight of Antoine's predecessors who resisted the temptation to unwrap and damage the mummies after they were obtained 100 years ago. But CT scanning has largely reduced the need and the damage of unwrapping.

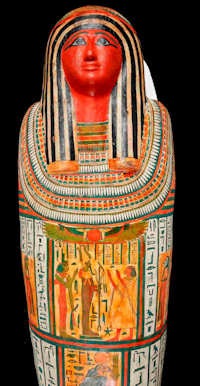

Cartonnage mummy mask of Satdjehuty, circa 1500 B.C., 18th Dynasty. All images are copyright of Trustees of the British Museum.

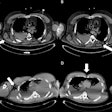

Cartonnage mummy mask of Satdjehuty, circa 1500 B.C., 18th Dynasty. All images are copyright of Trustees of the British Museum.In preparation for today's exhibition, three of the mummies were scanned with a dual-energy CT scanner from the Royal Brompton Hospital, London, with two x-ray sources, one at 80 Kv and one at 120 Kv. "This allowed us to capture images of unprecedented clarity including thin, delicate bandages as well as thicker parts of the body," Antoine said. "It also means we can correct for the metal artifacts such as amulets and we can accommodate for that in our images. We are seeing things that we never saw before."

The scanning process

"Much of the work we've done is transforming the thousands of slices into virtual images by putting the CT image data through volume graphic software -- VG Studio plus -- often used in car engineering for analyzing scans of car parts such as engines," Antoine explained.

The volume graphic software combined with the CT data is incredibly accurate and limits the assumptions that Antoine and his colleagues need to make. "We wanted to transform raw CT scan data into 3D volume and make as true a representation as science will allow."

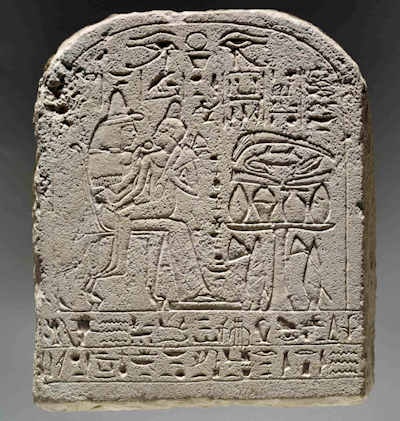

Round-topped limestone stela of Merysekhmet depicting the deceased child seated on the lap of his mother. 18th Dynasty.

Round-topped limestone stela of Merysekhmet depicting the deceased child seated on the lap of his mother. 18th Dynasty.Much of the work involved the time-consuming process of virtually separating the outer wrapping of the mummy from the skin, the bone, and the soft tissue in a process called segmentation that uses computer algorithms to determine where the various components start and where they finish.

But the upshot of all this work means that a visitor to the exhibition is able to participate in the interactive displays by virtually peeling away the bandages and layers of the body to reveal bone, tissue, and even blood vessels beneath.

Disease: Evidence of atherosclerosis, dental plaques

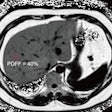

So detailed is the scanning that two of the mummies were found to have large calcified plaque deposits in their femoral arteries, a feature of atherosclerosis and a cause of cardiovascular disease. "These individuals would have been at risk of heart attacks and stroke," Antoine said. "We are unsure why. It might have been genetic or perhaps they were elite individuals who consumed a high-fat diet rich in cholesterol."

Antoine showed details of the atherosclerosis visible in the scans of a woman called Tamut. "This woman, Tamut, was around 40-50 years old, but her role as a temple singer from Thebes may not have involved a lot of activity so this could potentially fit with her atherosclerosis."

Tamut was also mummified with amulets over various parts of her body, part of the ritual burial at the time -- circa 900 B.C. An interactive digital visualization allows visitors to examine the ornaments revealed by CT scans as well as 3D-printed versions produced using the segmented scan data.

Pointing to two of the amulets over her lower abdomen, Antoine explained they covered the cut made by the embalmer to remove the internal organs, the so-called incision plates. Features on the amulet including the eye of Horus were believed to have magical healing powers and are only visible due to the sophistication of the dual-energy CT scanning. "The scanning also allows us to see feathers on other winged amulets, even the precise incision of the eye of Horus, which we would not have seen with scanners three or four years ago."

"Also, we can just make out leather strapping on her body, but we cannot yet make out the detail written on it -- we believe this might be the name of the ruling king. I hope that in five years time, scanning will provide this level of detail," he said.

Some findings came as a surprise even to a mummy expert. For example, the number of dental abscesses the mummies had. "These would have discharged pus into the mouth, their faces would have been swollen, and they would have been in great discomfort," he said. "I don't know how they managed to survive with such infections. Maybe they did have treatments, maybe they were more resilient then we think."

In fact, in the mummy known as "unknown man from Thebes," the CT scan data was segmented and inserted into a 3D printer to create a model of his jaw and teeth. "This man had huge dental abscesses. It's truly amazing that this mummy is totally intact but I can hold an exact replica of his jaw in my hand knowing his body has never been disturbed," Antoine remarked. "We are reaping the benefits of science like never before."

Mummy of an adult man, name unknown. Roman period.

Mummy of an adult man, name unknown. Roman period.The scanning has also revealed new insight into the embalming process. One mummy was found to have an embalming instrument made of reed or wood left inside the head. This would have been used to remove the brain through the nostrils -- a well-known part of the embalming process. "Very few embalming objects have ever been discovered but now we know such a tool was used as part of the embalming process," he said.

The pelvis as a measure of aging

Because CT image data are now more sophisticated than ever before, Antoine has used scanning to help develop a new method to determine the age of the mummies. Previously, dental wear provided the prime criterion for this purpose. "This is actually inaccurate because it is so dependent on diet and food processing," he noted. "But here I have used the wear and tear on one of the hip joints, the pubic symphysis, to age the mummy. To my knowledge, this is the first exhibition to systematically use this method."

The exhibition features an interactive display that enables the visitor to separate the hipbones and observe the surface of the pubic symphysis to assess how much age-related remodeling has occurred. When Antoine looked at the dental wear on the mummy and compared it with aging determined via wear on the pelvis, the two sources of information were consistent.

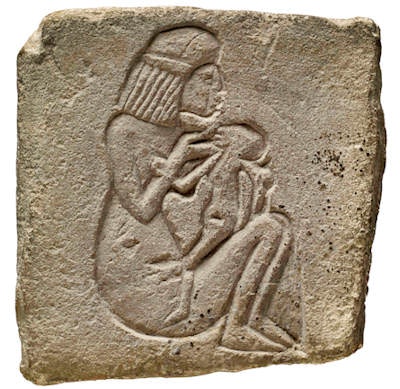

Limestone stela decorated with a representation of a woman suckling a child. 18th Dynasty.

Limestone stela decorated with a representation of a woman suckling a child. 18th Dynasty.What remains to be discovered?

As scanning technology improves further, finer details will be revealed, but in the future there might even be an opportunity to biopsy and analyze the histology of the cells and investigate diseases such as heart or lung disease, Antoine said. At some point, ancient DNA might also yield new discoveries.

"This is something we want to think about in the future," he said. "Ancient DNA doesn't really work very well because it comes from very hot environments, but we hope that as the science evolves then small amounts of DNA can be better amplified. But we need to think very carefully about whether the questions asked warrant any destruction to the mummies, however small."

With scanning technology and discussion of techniques to embalm and age, it is easy to forget these mummies were once real people. Returning to a theme he has strived to pursue throughout the exhibition, Antoine emphasized that primarily, the exhibition was about the remains of real people and human remains should never be referred to as objects. Indeed, "as with all human remains held in the British Museum, the exhibition aims to curate the mummies with care, respect, and dignity," he said.

In light of this, he explains that ancient Egyptians always wanted their names to be said when they were dead because they believed this would bring them back to life -- as such the exhibition closes with this writing on the wall: "O you who are alive on Earth ... Pronounce my name with abundant libation ... (Tomb of Petosiris, Hermopolis, about 330 B.C.)" to encourage visitors to pronounce the names of the three identified mummies: Tamut, Padiamenet, and Tjayasetimu.