High-resolution CT is playing a key role in revealing the secrets of ammonites, a mollusk that lived at the bottom of the sea about 400 million years ago, according to paleontologists from Germany.

Ammonite fossils share a similar helical shell as sea snails, which, as far as travel is concerned, are limited to crawling across the ocean floor. But Dr. René Hoffmann from the Institute of Paleontology at Ruhr-Universität Bochum (RUR) wondered if ammonites could actually swim, and he used high-resolution CT to determine that the ancient mollusks could move about freely in the water without expending much effort (Rubin Science Magazine, 7 April 2015).

Using high-res x-ray radiation, RUB paleontologists create images of fossil ammonites. © RUBIN, image: René Hoffmann.

Using high-res x-ray radiation, RUB paleontologists create images of fossil ammonites. © RUBIN, image: René Hoffmann.He used CT not only for rendering the structure of ammonite fossils in 3D, but to quantitatively analyze the structures. His key question: Could ammonites have generated enough buoyant force in a gas-filled shell to overcome their own weight and propel themselves easily in the water? The RUR team used CT analysis to reconstruct the internal structure from fossils, and used the volume and density of the shell material to calculate weight.

In order to obtain high enough resolution images of the fossils for analysis, they traveled to the site of a particle accelerator in Chicago that produces synchrotron radiation, or a monochromatic high-contrast x-ray radiation. They achieved a resolution of 0.74 µm, which rendered even the smallest internal structures visible. Today, even a basic micro-CT scanner produces resolution of 0.5 µm, delivering comparable image quality.

The infiltration of sediment and crystals into the structures complicated the measurements. But using special 3D software, they were able to define which areas belonged to the shell and which did not; this ultimately allowed the volume to be calculated, wrote Hoffmann and colleagues.

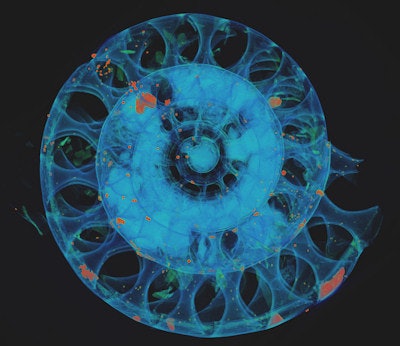

Left: Ammonites are relatives of the recent nautilus; both have a chambered external shell. The soft body was in the outermost chamber, i.e., the body chamber, which in this fossil has not been completely preserved. Right: 3D print of about 10 cm in diameter of an ammonite hatchling whose actual shell size is less than 1 mm. © RUBIN, photo: René Hoffmann.

Left: Ammonites are relatives of the recent nautilus; both have a chambered external shell. The soft body was in the outermost chamber, i.e., the body chamber, which in this fossil has not been completely preserved. Right: 3D print of about 10 cm in diameter of an ammonite hatchling whose actual shell size is less than 1 mm. © RUBIN, photo: René Hoffmann.To improve the precision of the weight estimations, the team undertook a second scan, this time alongside several high-precision objects made of aluminum oxide, silicate, and calcium carbonate, which enabled the grayscale to be determined precisely. The computer analysis showed the modern-day nautilus shell weighed 200.46 grams, very similar to the 203.5 grams shown on the actual scales. The weight analysis process worked.

For the fossil experiment, they weighed a very young ammonite using a hollow fossil from Russia that was about 165 million years old and had gotten embedded into the sediment shortly after hatching. The analysis supports the theory that such a hatchling with three to five shell chambers would have generated enough positive buoyancy to move about freely in the water, propelling itself with active swimming motions in the same way the modern-day nautilus does, the authors wrote, even though the ammonite has a much more complex internal structure. Indeed, no signs of crawling have been found in the fossil records.

Hoffmann plans to examine many more fossil shells with CT to determine the age at which newly hatched ammonites were able to swim and answer many other questions about their structure and movement.