Countering prior findings that cerebrospinal venous narrowing and multiple sclerosis (MS) go hand in hand, a study incorporating both x-ray venography and ultrasound found that venous narrowing is unrelated to MS. The new results were published online on 9 October in Lancet.

In the blinded, multicenter study of 177 individuals with and without MS, Canadian researchers found that just 2% of MS patients met the complex set of criteria for a condition known as chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency (CCSVI). On the other hand, the simple narrowing of any major vein was quite common -- but this occurred at the same rate in MS patients and healthy controls.

Venous narrowing was present in 74% of MS patients, 66% of siblings, and 70% of unrelated controls, and the difference wasn't statistically significant (p = 0.41), wrote researchers from the University of British Columbia and the University of Saskatchewan. The study was led by Dr. Anthony Traboulsee, assistant professor of neurology and medical director of the University of British Columbia Hospital MS Clinic (Lancet, October 9, 2013).

The findings undercut claims made by a 2009 study in Italy that gave many MS patients hope that their condition could be ameliorated or even cured by opening up narrowed cerebrospinal veins.

The Zamboni study

MS is a leading cause of neurological disability that is estimated to affect more than 2 million people globally. Its cause remains uncertain, but a specific vascular mechanism has long been thought to play a role in the disease.

The question of venous insufficiency and its relevance to MS began in 2009 when a paper by Zamboni et al concluded that the phenomenon was exclusive to MS patients based on findings from ultrasound scans, wrote Dr. Paul Friedemann, from Berlin's Charité Medical University, and Dr. Mike Wattjes, from VU University Medical Centre in Amsterdam, in a Lancet commentary accompanying the study.

"Dr. Zamboni's theory was that there were blockages in the veins that drain the brain -- the jugular veins and the azygous veins -- and those blockages would lead to congestion and the buildup of iron that would lead to inflammation. That condition was referred to as chronic cerebral spinal venous insufficiency, or CCSVI," Traboulsee said in an October 8 conference call.

Zamboni went on to treat patients with venous narrowing in a procedure called dilation therapy, and many ended up feeling better.

"Many of our patients became interested in [Zamboni's] theory, so we embarked on a series of investigations to try to validate Zamboni's findings," Traboulsee said.

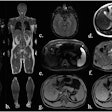

While the Zamboni study relied on ultrasound, catheter venography is regarded as the gold standard for examining venous stenosis, owing to its detailed depiction of venous anatomy and its ability assess collateral flow, stasis, and reflux patterns, the study team wrote.

In the new Lancet study, Traboulsee and colleagues were looking to clarify whether venous blockages are truly unique to multiple sclerosis. In addition, they wanted to evaluate the specificity and sensitivity of the Zamboni study's Doppler ultrasound criteria for CCSVI as compared to catheter venography, they wrote.

Zamboni and colleagues also hadn't blinded their researchers to the patient group, whether it was MS or healthy control patients. The new study ensured that the researchers did not know the patient's MS status.

Venography plus ultrasound

Traboulsee and his team recruited patients with MS, their healthy siblings, and unrelated healthy controls ages 18 to 65 years who had not undergone venous procedures or used vasoactive drugs. Participants were examined on tables so that the presence of MS could not be determined visually, and subjects were asked not to discuss their disease with the physicians performing the procedures to ensure that they remained unaware of patients' MS status.

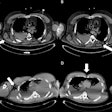

Venography was performed on the right and left internal jugular vein and the azygous vein, using a tilt table with patients seated upright; the venography protocol was standardized across three centers with training sessions held to ensure quality performance, according to the authors. Jugular vein stenosis was defined as greater than 50% narrowing compared to a reference standard. Azygous vein stenosis was defined as greater than 50% narrowing compared to the patient's largest normal segment.

The ultrasound equipment (MyLab Vinco, Esaote) was identical to that used in the 2009 study, with a 7-mm transducer capable of grayscale imaging. A cross-sectional area smaller than 0.3 cm² was considered positive for narrowing in the jugular vein.

"We sent our technologists to Zamboni's clinic and they learned his technique; we bought the exact same equipment that he was using, so that we were in the strongest position possible to reproduce his results," Traboulsee said.

Using Zamboni and colleagues' catheter venography classification of chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency, one (2%) of 65 patients with MS, one (2%) of 46 unaffected siblings, and one (3%) of 32 unrelated controls met the criteria of narrowing of any major vein at venography, the group reported.

When the researchers added evidence of physiological flow alterations to narrowing, 33 (51%) of 65 MS patients, 21 (45%) of 47 siblings, and 20 (54%) of 37 unrelated controls met the criteria for narrowing. Five percent of MS patients, 17% of the siblings, and 11% of the healthy controls did not meet any of the five Zamboni ultrasound criteria for the condition.

"We only found three people out of 177 who had this feature -- one in each group -- and it didn't seem to make sense," Traboulsee said in the conference. "We found with ultrasound we could detect the CCSVI criteria in around 40% to 50% of people, but when you look at the accuracy of ultrasound versus catheter venography, you might as well flip a coin. They just didn't agree."

Rarity of venous stenosis

"We noted no significant differences between the three groups of participants when considering unilateral or bilateral presence of positive criteria," the authors wrote. "There was no indication of any effect of sex, age, or study site on ultrasound findings. ... Asynchronous valve movement was the most frequent structural abnormality on ultrasound" and was found in 34% of patients.

And ultrasound criteria for CCSVI had poor agreement with catheter venous criteria for the same condition, regardless of patient status.

Overall, the study results "provide no evidence that extracranial venous anatomy differs between patients with multiple sclerosis, their unaffected siblings (including monozygotic twin pairs), and unrelated healthy controls," Traboulsee and colleagues wrote. "Catheter venography findings of chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency as described by Zamboni and colleagues are therefore rare findings and do not distinguish patients with multiple sclerosis from healthy controls."

Close to three-fourths of participants had venous narrowing at angiography, whether or not they had MS, a finding that had not been previously reported.

"Moreover, with ultrasound, we did not find differences in the rates of Zamboni-defined chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency (two or more positive criteria of five) or valvular abnormalities between healthy controls and participants with multiple sclerosis," they wrote. The agreement between ultrasound and catheter venography for the detection of venous narrowing was very low, with catheter angiography rarely reporting cerebrospinal venous insufficiency.

Therefore the results "also challenge both the validity of ultrasound for the purpose of detecting chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency and its existence as a disorder," they wrote. "The significance of venous narrowing to multiple sclerosis symptomatology remains unknown."

An 'innovative' study

In their accompanying commentary, Friedemann and Wattjes noted that the use of both ultrasound and catheter venography were highly innovative because of venography's gold-standard status. An important finding was that ultrasound sensitivity for venous narrowing was very low at 40%, with specificity of 64% in results that were nearly identical across the three study groups. In addition, the proportion of patients with 50% or greater narrowing was different across study groups.

The study offers evidence that one modality's findings do not necessarily correspond to another's, and it "lends further weight to arguments based on pathophysiological and methodological concerns that no indication exists for venous angioplasty in multiple sclerosis," Friedemann and Wattjes wrote.

Traboulsee and colleagues' solid and well-balanced study "sounds a death knell for the hypothesis of chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency as a disease entity," they concluded.

"We found that ultrasound in general is not a reliable way to investigate venous narrowing," Traboulsee said.

Going forward, the researchers plan to investigate why MS patients seem to benefit from dilation therapy, also known as "liberation therapy," and they will document the findings with catheter venography and other imaging modalities, he said.