On 6 October 2003, Sir Peter Mansfield received the most important phone call of his life. It came from Stockholm, and it was to inform him that he would share the 2003 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his contribution to MRI. His new autobiography, The Long Road to Stockholm1 is an enlarged version of his autobiography for the Nobel Prize presentation.2 It benefits from some added personal background -- and details his journey to the Nobel Prize.

There is something voyeuristic about reading autobiographies and memoirs, in particular if there is a prevailing feeling that the author accomplished something noteworthy. Yet, in many ways Mansfield's life resembles that of numerous others who grew up during and after World War II.

This portrait of Sir Peter Mansfield was painted in 2008 by Stephen Shankland RP. Image courtesy of the U.K. Royal Society of Portrait Painters and National Portrait Gallery.

This portrait of Sir Peter Mansfield was painted in 2008 by Stephen Shankland RP. Image courtesy of the U.K. Royal Society of Portrait Painters and National Portrait Gallery.

Mansfield was born in London on 9 October 1933. He describes his prewar and wartime childhood in southern England, his apprenticeship as a printer, evening-school studies and work in rocket propulsion development, and his "salad days" at university. He also outlines his postdoctoral years at the University of Illinois, his sabbatical at the Max Planck Institute in Heidelberg, Germany in the early 1970s, and his career in academic physics at the University of Nottingham, U.K. -- including his famous patent fights and infamous department conflicts.

His autobiography touches on his social rise from the son of a laborer and a waitress; later in life, he would become "Sir Peter," a Nobel Prize winner. Yet, human insights and visions are sadly lacking, and the reader remains unenlightened about his early years. The book is mainly interspersed with leaden scientific details, and peculiar descriptions of fellow scientists. Mansfield's autobiography would have benefited from shortening and more professional editing.

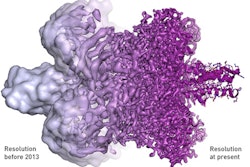

Peter Mansfield is a theoretician with a deep understanding of the physics of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and MRI; his main research area in the heyday of MRI application development was echo-planar imaging (EPI), the fastest known data acquisition technique. However, he never understood the world of (what he calls) the "medicos" and did not fathom that high image quality and spatial resolution might be more important to reach a diagnosis in clinical research and patient routine than the possibility to create blurry images or movies in less than a second. EPI has finally found its place in applications like diffusion and functional imaging.

Like many Europeans in the field, a stay in the U.S. opened Mansfield's eyes to the American way of science, as it was attainable for scientists until the late 1980s: freer, richer, more open, and less hierarchical than in Europe. His stay at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign in Charles P. Slichter's research group in 1962 and 1963 allowed him to acquire the basics in NMR of solids. This was his first impression, a typical impression of a young European scientist arriving in the U.S.:

When I first arrived in Slichter's group, I was the only postgraduate person present. Nevertheless I felt greatly inferior, because the range of knowledge that all the graduate students seemed to have of physics, electronics, and various other subjects appeared to me at the time to greatly to exceed my own knowledge in these areas, particularly of theoretical physics.

Except for a period during 1972/1973, when he worked at the Max-Planck-Institut für Medizinische Forschung in Heidelberg, Mansfield spent the rest of his career in Nottingham. Raymond Andrew, a great and outstanding British NMR scientist of the time, opened the doors for him at this university. He walked in, and after some years the other scientists, Andrew included, walked out. Mansfield records his view:

The result of these moves created a considerable vacuum at Nottingham, but the important thing from my point of view was that all the infighting and intrigue that had gone on over the last there or four years stopped.

The subtitle of the autobiography is "The story of magnetic resonance imaging," but long passages of the text are misleading, nagging, and arrogant. Mansfield's life story isn't the story of magnetic resonance imaging. When he heard about Paul Lauterbur's invention of MR imaging, Mansfield appeared to "jump on the bandwagon" -- but his autobiography tries to convince the reader otherwise.

Soon afterward, Mansfield's acumen in acquiring and enforcing patents in his NMR research fields became profitable. With a lot of emphasis on details, he describes his interaction with the university administration, numerous companies, and politicians all the way up to Gordon Brown, who was at that time junior minister in the opposition Labour Party and who later became prime minister. Mansfield received his knighthood in 1992, and finally at the end of the long road, he was chosen to share the 2003 Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology with Lauterbur. He curmudgeonly recalls:

When we read the detail in the information pack of the Nobel Prize committee, it became apparent that they would only cover the costs of travel to Sweden for me and my wife. A number of other people were eligible to come but at their own cost. I decided that the sensible thing would be to limit the number of guests to our close family, namely my two daughters, their husbands, and the four children.

Usually, prize recipients take their collaborators with them because research is a team effort; the invitation to join the ceremony is an acknowledgement and reward for their contribution to the common goal.

Although he lived abroad for some time, Mansfield appears to remain closely attached to the English class system. The late Duke of Bedford's œuvre, The Book of Snobs, makes perfect supplementary reading to this autobiography.3

This column has been shortened and edited by the publishers. The complete column can be found at www.rinckside.org.

References

- Mansfield P. The Long Road to Stockholm: The story of MRI, an autobiography. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013.

- Mansfield P. Autobiography. In: Frängsmyr T, ed. The Nobel Prizes 2003. Stockholm: Nobel Foundation; 2004.

- Russell JIR, Duke of Bedford, in collaboration with George Mikes. The Duke of Bedford's Book of Snobs. London: Peter Owen; 1965.

Dr. Peter Rinck, PhD, is a professor of diagnostic imaging and the president of the Council of the Round Table Foundation (TRTF) and European Magnetic Resonance Forum (EMRF).

The comments and observations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions of AuntMinnieEurope.com, nor should they be construed as an endorsement or admonishment of any particular vendor, analyst, industry consultant, or consulting group.