One of MRI's earliest milestones -- the first scan of a human being -- may have occurred due to divine intervention, the controversial U.S. scientist Dr. Raymond Damadian has claimed. Damadian shared his thoughts on the early development of MRI in a fireside chat at the recent International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM) annual meeting.

The history of MRI is covered comprehensively in a textbook by Prof. Peter Rinck (see An Excursion into the History of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, pages 384-387 [slides 18-21 of PDF] on Damadian). But some observers still claim Damadian conducted the first MRI scan of a human being in 1977 in his research lab at the State University of New York (SUNY) Downstate Health Sciences University, and they believe that Damadian's contributions to MRI have been overlooked, in particular when a Nobel Prize in 2003 was awarded to Paul Lauterbur, PhD, and Sir Peter Mansfield, PhD -- snubbing Damadian.

Some Damadian supporters think that his support for creation science -- a form of creationism that aims to find scientific interpretations for the Bible -- was behind the Nobel Committee's snub. This theory was described in detail in a 2003 article in Smithsonian Magazine.

Damadian keeps a lower profile now compared to 18 years ago, when he directed a publicity campaign castigating the Nobel Committee's decision in a series of national newspapers. His appearance at ISMRM 2021 focused on the early days of MRI development.

MRI's greatest contribution to medicine is pixel contrast that allows for "almost limitless detail" in imaging the vital tissues of the body, Damadian told session facilitator Greg Hurst, PhD, professor emeritus of radiology at SUNY Upstate in Syracuse, New York.

"We had this miracle: We could see all the vital tissues of the body in almost limitless detail for the first time in medical history," Damadian said.

Damadian was born in New York in 1936, earning his medical degree at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in 1960 and going on to a residency at SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University.

In the 1970s, he began working on the first MRI scanner with postgraduate assistants Lawrence Minkoff, PhD, and Michael Goldsmith, PhD, and named it Indomitable. Using the device, the team produced the first human image -- of Minkoff's chest -- in 1977. Damadian founded the company Fonar in 1978; it made the first commercial MRI machine in 1980.

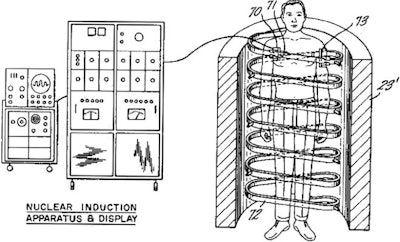

An image from Dr. Raymond Damadian's original MRI patent, "Apparatus and method for detecting cancer in tissue."

An image from Dr. Raymond Damadian's original MRI patent, "Apparatus and method for detecting cancer in tissue."In the ISMRM talk, Damadian described how his involvement with MRI began as he was researching the biophysics and biochemistry of the origin of the electricity of life. A colleague suggested he make use of a new technology, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), to measure chemical signals using bacteria samples from the Dead Sea. The data gleaned suggested that perhaps the imaging technology could visualize live chemistry of human tissue.

"We discovered that the NMR signal in cancer tissue differed markedly from healthy tissue, which meant that, in principle, you could ... detect cancer wherever it was [in the human body as well]," Damadian said.

Although Damadian faced skepticism as he continued his efforts to develop a scanner large enough to image humans, he pressed on. He and Goldsmith and Minkoff used large circular coils of niobium-titanium wire for the magnet because the wire was superconducting, but procuring the wire was quite the feat: He needed 30 miles of it.

Damadian at first postulated that he could attach separate lengths of wire together to get the 30 miles of wire he needed, but he became concerned that the joints between lengths might destroy the superconducting effect. He contacted the wire supplier, Westinghouse, to learn how to make the joints.

"I told him I was trying to build a magnet big enough for a human being ... but not how much wire I needed," Damadian said. "[This engineer told me that] Westinghouse was going out of the business of making this superconducting wire, [and that he had] 30 miles of wire in his warehouse he would sell me for 10 cents on the dollar."

Damadian couldn't believe it: He had the funds to buy the wire at that price and went to pick it up the next day.

"I told this story to my in-laws, this sudden coincidence with the wire," he said. "But my mother-in-law told me, 'Ever since Dad and I learned you want to build this, we've been praying for you and your success. This availability of the wire is not a coincidence, it's an answer to prayer.' "

Damadian was the first to volunteer to be imaged in the scanner -- "No one else would get in there," he said -- but when the team tried to image him, they couldn't pick up any signal.

"[Goldsmith] said it was because I was too fat for his coil," Damadian said.

Minkoff eventually offered to get scanned, and in 1977 an image of his chest became the first MRI scan of a human being.

Decades later, MRI benefits countless patients. For Damadian, the development of the modality has truly been miraculous.

"The way I see it, this wasn't me doing this -- this was God's gift," he said. "That I got 30 miles of wire at 10 cents on the dollar the instant I needed it is proof that it was God's intention to produce this scan for the benefit of mankind."