Gonad shielding of children who undergo a pelvic examination may not be necessary if low-dose optimized digital radiography (DR) equipment is used, according to a new study by Dutch researchers published online first in Insights into Imaging.

If properly positioned, gonad shielding can lower radiation dose to the testes by about 95% and to the ovaries by about 50%, the study authors noted. However, the problem is that proper placement to cover the target area but none of the bony pelvic structures can be tricky, and it can result in retakes or suboptimal images that do not show all diagnostic images.

Radiologists at Maastricht University Medical Center believe that using gonad shielding may have more disadvantages than advantages. They compared 500 anterior-posterior (AP) pelvic radiographs taken in 2007 and 2008 using gonad shielding with 195 examinations taken in 2010 without gonad shielding. Their objective was to assess the quality of the images produced with respect to loss of diagnostic information and re-evaluate the benefit of shielding in terms of attainable radiation risk reduction (Insights into Imaging, 25 September 2011).

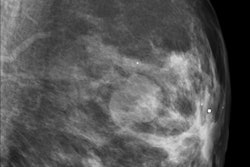

All the examinations for both time periods were performed using flat-panel DR systems (Axiom Aristos FX Plus, Siemens Healthcare). The systems had preprogrammed protocols, which set the high voltage (kVp), additional filter, focus to image-detector distance, and either a fixed tube current exposure (mAs) or the automatic exposure control (AEC). The protocols also indicated whether bucky antiscatter grids were needed. Age-dependent protocols with fixed technique parameters were used for children younger than age 10. Sized-based protocols were used for patients ages 10 to 15 years. The effective dose without gonad shielding ranged from 0.008 to 0.098 mSv.

The children ranged in age from infancy to 15 years. In 2007-2008, 61% of the patients imaged were girls, yet placement of shielding to protect the ovaries was incorrect in at least 87% of cases, the researchers found. For infants up to 12 months, an age group that represented almost one-third of the girls, shielding was properly placed only 3% of the time. Retakes had to be performed for more than half of the infant population, and retakes also had to be performed for 28% of patients ages 1 to 5 years (28% of the total of 304 female patients).

The percentage of improperly shielded testes was lower for boys, but still was quite high: a low of 52% for boys ages 1 to 5 years, representing 21% of the male group. It was highest at 71% for boys ages 5 to 10 years. However, only eight retakes were needed for this pediatric male group, seven of whom were for infants.

Based on the appearance of images when they were rereviewed, retakes had been performed only if they were of extremely poor quality and a diagnosis could not be made, according to lead author Dr. Marij Frantzen of the department of radiology. In one case in which a retake had been performed, a poorly positioned shield had covered an osteomyelitic lesion in a boy.

Gonad shielding was a necessity when radiation dose exposure for a pelvic AP exam was high. In the 1950s, it averaged about 10 mGy, but today the figure is a few tenths of a milligray. Staff at Maastricht decided in 2010 that it would be more beneficial to have images of constant good to excellent quality for all children rather than use gonad shielding with its inherent placement difficulties.

Without gonad shielding, the hereditary detriment adjusted risk for girls ranged between 0.1 x 10-6 and 1.3 x 10-6, and for boys between 0.3 x 10-6 and 3.9 x 10-6, depending upon their age. When shielding is properly positioned, the reduction in hereditary risk for girls was on average 6% of the total risk of the radiography and 24% for boys.

After making these calculations, Frantzen and colleagues still believed that the trade-off in increased radiation dose exposure to the testes and ovaries would be outweighed by having the peripheral zones of the pelvic bones displayed and providing images of excellent diagnostic quality to radiologists for interpretation. But it is imperative that clinical staff use state-of-technology, low-dose DR systems and protocols that adhere to the as low as reasonably achievable (ALARA) principles. Otherwise, they should continue to use gonad shielding with the realization that attention to placement is imperative, the authors noted.