CT angiography (CTA) and other methods can shed light on death investigations in ways that autopsy can't. CTA, for example, allows doctors to look for bleeding points, while dual-beam CT depicts soft-tissue differentiation and bruising, and the technique is useful to investigate postsurgical deaths and identify trauma areas deep in the pelvis and around the spine, which are usually difficult to see without extensive dissection.

"Techniques used in the living will be increasingly applied to the dead, as well as those that aren't -- such as injecting air into structures such as the chest cavity to better visualize CT findings," noted pathologist Dr. David Ranson, deputy director of forensic services at the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine (VIFM) in Melbourne, Australia.

Death investigations now use a collection of tools that make a formidable complement -- and often alternative -- to the traditional autopsy. Imaging has already halved the forensic autopsy rate in Melbourne, and emerging techniques are gaining ground for the examination of deceased subjects.

For Ranson, CT provides a 3D record that can be consulted long after the body has been buried or cremated, when improved software might provide better detection and visualization of disease, foreign objects, and trauma, or when a second opinion is desired. Other benefits include early detection of dangerous elements, including sharp objects such as mesh or stents, and of infectious diseases indicated by cavitating lesions found in tuberculosis, for example.

In the recent spate of terror attacks, imaging has proved pivotal in both identifying victims and circumstances.

"The body is a structure that absorbs the explosion and is often penetrated by glass, brick, and fragments of the device. These objects are protected from subsequent fire, and the body becomes a preserved part of the crime scene. The objects can be identified and carefully extracted to allow for forensic examination," Ranson told ECR Today ahead of the congress. "In addition, whole-body CT is incorporated into the disaster victim identification process and has been recently used in Belgium and France."

To illustrate how imaging can assist in the investigation of other objects in a forensic setting, he described a specific case.

"We were brought a suspicious suitcase. CT imaging revealed that a body was folded up inside it and that it had suffered trauma. Detection of surgical prostheses meant that we could also identify the victim, all before the suitcase was even opened," he said.

In Melbourne, around 5,500 to 6,000 cases are handled at the VIFM each year to receive a routine whole-body CT scan. Barring dissection, automatic permission to examine a body is granted once it is registered, which includes taking fingerprints, oral swabs, blood and urine samples, and performing x-ray, CT, dental scans, and toxicology. Armed with these results, Australian forensic pathologists meet with the judge or coroner to decide whether autopsy is needed. In the U.K., by comparison, the decision is taken before there are any preliminary results, leading to 50% of coroner-reported cases in the U.K. undergoing autopsy.

Ranson hopes that over the next five to 10 years all Australian mortuaries will use CT scans routinely. He believes developments such as software that stretches out the bones to look for tumor metastases or skeletal multitrauma will be extended to death investigations in the future and that greater use will be made of MRI, which like CT is ideal for tissue differentiation and depiction of edema bruising.

Improved clinical work

At today's session, Dr. Thomas Ruder, a consultant radiologist at the Institute of Forensic Medicine at the University of Zurich and a clinical radiologist at the University Hospital of Bern, plans to describe how postmortem imaging can improve clinical practice.

"This is an interesting field for clinical radiologists, and there are great opportunities for knowledge transfer and research," he told ECR Today. "By correlating images to autopsy, radiologists can better understand CT and MR findings. With no issue of radiation exposure, we can learn how kV and mAs affect image quality. Also we can learn how to accurately distinguish between findings and interpretation, and this improves the quality of clinical reports."

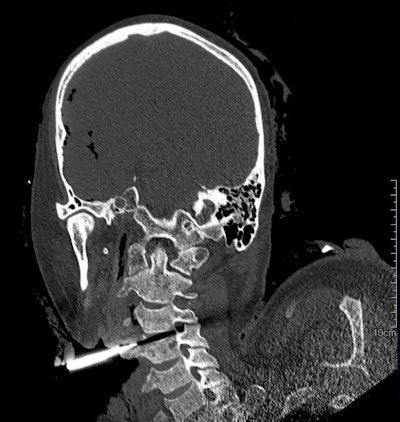

3D-rendered image shows the exit wound of a ballistic projectile in a neutral bloodless manner favored by juries and investigators. Image courtesy of Dr. Thomas Ruder.

3D-rendered image shows the exit wound of a ballistic projectile in a neutral bloodless manner favored by juries and investigators. Image courtesy of Dr. Thomas Ruder.Ruder often uses a side-by-side comparison of antemortem images from local hospitals with postmortem CT images to identify subjects. Postmortem CT images may be reformatted to match almost any type of antemortem images, even high-quality ultrasound, he noted.

Postmortem CT lung findings are particularly challenging. Internal lividity may look like pulmonary edema, and it can even mask pneumonia.

"It is hard to correlate lung image findings to autopsy. One can't cut the lung into thin cross sections, and most likely pathologists won't find focal findings in autopsy as seen in radiology. This means that we have to be very careful with the interpretation," he said.

Awareness of the pitfalls related to forensic questions is also vital. Postmortem CT can, for example, identify the cause of death in a case of hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage, but imaging cannot clarify the manner of death in such cases; hypertension may be a natural event or due to cocaine intoxication, and toxicological analysis is required to determine this.

The future of postmortem imaging looks set to depend on what is of most interest to investigators and, in the case of cardiac death, on their willingness to accept a probable cause based on imaging findings over a certain cause of death provided by autopsy, according to Ruder. This will shape research and allow better assessment of the true practical potential of imaging.

Working in a legal setting comes with specific rules and guidelines, noted Dr. Rick R. van Rijn, pediatric radiologist and chair of forensic radiology at the Emma Children's Hospital at the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam.

"First, everything should be kept confidential, and all documents and images should be accounted for, including a record of who has access to them in order to preserve the chain of evidence," he stated. "Second, reporting has to be adapted in order to make the radiology report accessible to lay people, which requires a completely different skill set to clinical radiology."

He also suggested forensic pediatric radiology might not appeal to everybody.

"The radiologist must be willing to act in court as an expert. Sentiments can be very strong, especially in cases of abusive head trauma," he said.

Originally published in ECR Today on 2 March 2017.

Copyright © 2017 European Society of Radiology