VIENNA - Gastrointestinal (GI) imaging looks poised to make another quantum leap forward in the years ahead, as fluoroscopic techniques are left behind and the field develops beyond simply anatomical imaging, embracing increasingly functional and quantitative techniques, according to speakers at yesterday's special focus session on GI imaging.

Over the past decade or so, there have been major advances in abdominal imaging in CT, MRI, and PET/CT. Given the emphasis on dose reduction, radiation-free modalities are now taking center stage as radiology goes increasingly mobile.

Dr. Simon Jackson from Plymouth, U.K. Image courtesy of the European Society of Radiology.

Dr. Simon Jackson from Plymouth, U.K. Image courtesy of the European Society of Radiology.

"As well as the functional techniques, we're moving into quantitative techniques with which we can look at cellularity, perfusion, and inflammation," said session moderator Dr. Simon Jackson, a consultant GI radiologist at the Plymouth University Hospitals NHS Trust, U.K., and past chairman of the British Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology. "We're moving into the next era; that is, the era of personalized medicine."

This all translates into patient-tailored therapies, and GI imaging has a fundamental role to play here in driving and defining the primary treatment decision and monitoring therapeutic response. His advice to ECR delegates was to embrace the new responsibilities in the era of personalized medicine.

"Technological advances have led to a revolution in GI imaging, but very importantly, all these techniques are complimentary," he said. "Clinical applications are changing, and as radiologists, we've got to understand the strengths and limitations of each diagnostic technique and where they sit within the clinical management of patients."

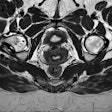

MRI fluoroscopy can replace conventional techniques in swallowing and gastric emptying, and it can also replace conventional methods and increase understanding of a patient's condition in the case of both gastric emptying and the small bowel, said Dr. Stuart Taylor, who heads the development of functional MRI in oncology and GI diseases at University College London Hospitals (UCLH) NHS Foundation Trust in London.

Protocols require a technique with high temporal resolution and reasonable spatial resolution, and he explained that the two main approaches are T1-weighted gradient echo-based imaging (usually with gad spiking of oral contrast) such as FLASH, and T2-weighted imaging (usually with nonspiking of oral contrast) such as TrueFISP or Fiesta.

Dr. Stuart Taylor from London. Image courtesy of the European Society of Radiology.

Dr. Stuart Taylor from London. Image courtesy of the European Society of Radiology.

The main benefits of MRI fluoroscopy are its multiplanar imaging capability, the full view of soft-tissue structures (not just the lumen), and the lack of ionizing radiation, which is of particular value for repeat studies. The drawbacks are that its temporal resolution is up to 10 times less than standard fluoroscopy, the requirement for the patient to be in a supine position, lack of fine intraluminal detail, and the fact that it takes 20 to 30 minutes, according to Taylor.

Gastric motility can be broadly divided into changes in gastric volume, for which the gold standard is the barostat device, and measurement of peristaltic activity/emptying rate, for which the gold standard is scintigraphy, he stated.

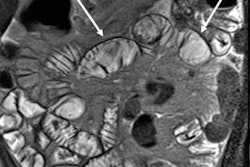

Assessment of small bowel motility using MRI can be of particular value, he continued. Usually it is vital to distend the bowel, as is done for MR enterography, e.g., with 1 L of 2% to 3% mannitol. If a detailed physiological study is being conducted, it is necessary to control the time of day, smoking, caffeine intake, medication, etc. Basic anatomical data are required to plan motility, and the aim is to cover most of the small bowel volume, using a typical slice thickness of 1 cm, breath-hold acquisition at each slice position, and 10 to 25 slice positions to cover the whole small bowel.

Motility information can shed light on conditions such as diabetic neuropathy, pseudo-obstruction, Parkinson's disease, postsurgical ileus, autonomic failure, bacterial overgrowth, and Crohn's disease. However, among the remaining technical challenges are the need for more rapid whole-volume small bowel data acquisition, errors due to through plane motion of loops, automated region-of-interest (ROI) placement, free breathing, tagging, and the requirement for improved registration techniques.

"MRI fluoroscopy is possible and may have uses in long-term follow-up of patients," he said. "MRI assessment of gastric emptying is now established as a clinical and research tool."

MRI assessment of small bowel motility is possible with increasingly sophisticated software tools to quantity segmental and global motility, and there are multiple potential clinical applications, noted Taylor, who is co-author of a relatively recent article on this topic, titled "The future developments in gastrointestinal radiology" (Helbren et al, Frontline Gastroenterology, July 2012, Vol. 3:Suppl 1, p. i36-i41).

Originally published in ECR Today on 10 March 2013.

Copyright © 2013 European Society of Radiology