Small-bowel tumors are particularly tough to diagnose due to their clinically silent evolution and nonspecific manifestations, but appropriate use of CT and sound knowledge of imaging characteristics are a massive help, according to award-winning Spanish research.

Small-bowel tumors are relatively rare, representing 3% to 6% of all gastrointestinal neoplasms and less than 2% of all malignant tumors. In addition, most small-bowel neoplasms are small, especially in the early stages, and this makes diagnosis by conventional radiologic examinations difficult and often delayed, explained Dr. M. Pardo Antunez, a fourth-year resident, and colleagues, in the department of diagnostic imaging and therapeutics at Hospital General Universitario Vall d´Hebron in Barcelona, Spain.

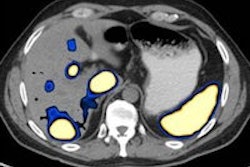

"Although the differential diagnosis for a small-bowel tumor is extensive, various small-bowel neoplasms have characteristic features at CT that may aid in making a diagnosis," stated the authors, whose ECR 2015 e-poster received a prestigious cum laude award. "MDCT (multidetector CT) enteroclysis, which combines the advantages of MDCT examination of the abdomen and the challenge of enteroclysis, is a useful method in the diagnosis and staging of the small-bowel neoplasms."

The Barcelona group summarized the main tumor types:

Lipomas are relatively common, benign, small-bowel tumors that present as a well-circumscribed intramural lesion mass in the ileum rather than in the jejunum. MDCT findings of a homogeneous mass with low attenuation are diagnostic, but they may enlarge and show necrosis, calcifications, ulcerations, or even cystic degeneration, they noted. Although most small-bowel lipomas are asymptomatic, clinical manifestations can include gastrointestinal bleeding due to ulceration, or incomplete small-bowel obstruction episodes caused by intussusception.

Leiomyomas are mesenchymal tumors originating from the muscularis propria of the small bowel. The jejunum is the most frequent location of leiomyomas, followed by the ileum and the duodenum, although they are rare in the small intestine. They usually present as a rounded submucosal well-circumscribed mass with homogeneous enhancement, and can ulcerate and cause gastrointestinal bleeding.

Neurofibromas of the small bowel are mesenchymal tumors, often developed in patients with Von Recklinghausen disease, as ganglioneuromas or fibrosarcomas. They have also been reported in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2b (MEN 2b), juvenile and adenomatous colonic polyposis. Rarely, they can occur as isolated tumors, with no associated systemic syndromes. Clinical manifestations include abdominal pain, palpable mass, bleeding due to necrosis or ulceration of the mucosa, or obstruction due to intussusception. MDCT usually demonstrates a well-defined, homogeneous mass with moderate enhancement. Histopathologic analysis demonstrating proliferative spindle cells and the immunohistochemical analysis is necessary to make the final diagnosis.

Adenomas are the most common asymptomatic benign small-bowel tumors. Three major histological types are tubular, tubulovillous, and villous, and they may develop as pedunculated or submucosal lesions. There is good evidence for an adenomacarcinoma sequence in the small intestine as in the colon, so they must be considered premalignant lesions. They appear mainly in the duodenum, in the ampullary and periampullary region, but also in ileum (ileocaecal valve). Most adenomas occur singly and sporadically, but multiple adenomas may be found, especially in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. MDCT can show mural nodular thickening or a polypoid mass, with homogenous enhancement, frequently located in the periampullary region.

Adenocarcinoma is the most common primary malignancy of the small bowel and accounts for 40% of cancers, although they are 40 to 60 times less frequent than colon carcinoma due to the rapid turnover of the intestinal cells and rapid transit time of the small bowel. The predominant location of adenocarcinoma is the duodenum and proximal jejunum, with the incidence decreasing distally, except in Crohn's disease. Adenocarcinoma accounts for two-thirds of duodenal neoplasms and approximately half of all jejunal neoplasms.

Small bowel adenocarcinomas may be polypoid, infiltrating, or stenosing. Duodenal adenocarcinomas are usually more circumscribed with a polypoid or protuberant appearance and arise in the periampullary region. Conversely, jejunal or ileal lesions tend to be larger, annular, and hetrogeneous constricting tumors with circumferential involvement of the intestine wall. The luminal narrowing may result in partial or complete small bowel obstruction. Other common presentations of adenocarcinoma of the small bowel include overt or occult gastrointestinal bleeding, and weight loss and jaundice. Adenocarcinoma is often discovered late, with lymph node involvement.

Neuroendocrine tumors, formerly called carcinoid tumors, arise from the cells of the neuroendocrine system and produce peptides, neuroamines, and vasoactive substances that lead to many clinical syndromes. They include true carcinoid tumors (well-differentiated neoplasms of the diffuse endocrine system), small-cell carcinomas (poorly differentiated endocrine neoplasms), and malignant large-cell neuroendocrine carcinomas, the authors concluded.

Small bowel obstruction

CT is also the modality of choice if an acute small-bowel obstruction (SBO) is suspected, pointed out Dr. Elena Diez and colleagues from the radiology department at UCR de la CAM Hospital Infanta Leonor in Madrid.

"Small bowel obstruction is a common clinical condition for which safe and effective management depends on a rapid and accurate diagnosis," they explained in another ECR 2015 e-poster. "The role of CT in the diagnosis of small-bowel obstruction has expanded since it's a rapid and noninvasive technique, widely available, and more accurate in determining the presence, site, cause, and degree of the obstruction, as well as in identifying associated strangulation. CT allows depiction, not only of the bowel wall, but of the mesentery, mesenteric vessels, and peritoneal cavity as well."

However, the relatively high radiation dose of CT raises concern for its use in patients requiring repeat imaging studies. Intraluminal contrast material is not usually administered as the intraluminal fluid itself serves as a natural negative contrast agent, but administration of iodine water-soluble contrast material 60 to 120 minutes prior to the CT may help to assess the grade and severity of partial SBO.

Intravenous contrast material is usually administrated except in case of contraindications such as allergy or renal failure. Diez et al use about 100 ml of contrast material administered at a rate of 2 ml/sec to 3 ml/sec. They scan the abdomen and pelvis with a helical technique during a single breath-hold with a collimation of 5 mm to 7 mm and a pitch of 1 to 1.5.

CT findings in SBO are dilated small-bowel loops greater than 2.5 cm with distally normal-caliber or collapsed loops. Multiplanar reformatted views help to identify the cause, level, and grade of obstruction, and wall thickening with lack of enhancement, engorged mesenteric vessels, free intraperitoneal fluid, pneumatosis intestinalis, and gas in portal vein or pneumoperitoneum may be seen in cases of complications, they continued.

"Complete versus low grade or partial obstruction is determined by the degree of collapse, by the intestinal content distal to the obstructed site, as well as by the passage of the oral contrast material to distal bowel loops in case it's administered," they noted. "Although CT has a high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing high-grade obstructions, it's not the ideal method for diagnosis of low grade obstructions, for which CT should be complemented by a contrast study."