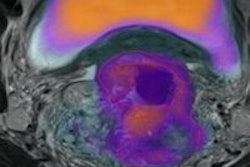

VIENNA - PET/MRI allows superior early detection and evaluation of cancers as they disseminate around the body. That was the key message of Dr. Heinz-Peter Schlemmer in his talk in Saturday's new horizons session at ECR 2013.

Taking the two sources of information together provides insight into both the biology and location of the tumor or metastases inside the body, according to Schlemmer, a professor of oncologic radiology at the University of Heidelberg, Germany, and chair of radiology at the German Cancer Research Center. Combined PET/MRI can help radiologists to detect cancer early and characterize its biological behavior. Also, it's important to consider the heterogeneity of tumors, which are an evolving structure that started on one side of the organ and disseminated.

"Different tumors in different parts of the body vary in their behavior, and we need to assess these differences and adapt the therapy to the patient accordingly," he noted. "We also need to monitor therapy to evaluate the intervention across the body. PET/MRI will help us to individualize and stratify therapies to the patient."

Commenting on this point, Dr. Herbert Kressel, from Harvard Medical School in Boston, U.S., who attended the presentation, said he believed that heterogeneity was the sweet spot for this technology.

"PET/MRI is the only thing that can approach imaging the dimensions of tumor heterogeneity at this time," he told ECR Today. "I think this is an enormously promising area, and this evolving concept of cancer cells having their own ecology that adapts to the surroundings can only be displayed by a multidimensional approach."

"The same tumor in different places at different points in time behaves differently and needs to be treated differently. I think this new technology is the only way I can imagine to get a handle on the many dimensions," he added.

Dr. Heinz-Peter Schlemmer from Heidelberg, Germany. Image courtesy of the European Society of Radiology.

Dr. Heinz-Peter Schlemmer from Heidelberg, Germany. Image courtesy of the European Society of Radiology.

Schlemmer pointed out that if tumor cells have their metabolism blocked in one place, then they move elsewhere. "Also, there are indications that when you irradiate a tumor, it starts to metastasize and the reason is that initially the blood flow decreases and then the cell realizes it would be better off if it moved."

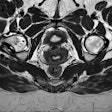

He acknowledged that he had seen this in prostate cancer commonly and that it was visible with PET/MRI. However, he tempered his enthusiasm by stressing that PET/MRI is only as good as the radiotracer available.

"Without the right radiotracer, it is only an MRI," Schlemmer said, adding that the radiotracer makes the molecules and pathways visible. "This allows the radiologist to see metabolism and molecules distributed on the cell surface with sensitivity in the picomolar range, the most sensitive level available."

By way of example, he said there were some new developments in prostate cancer, such as the novel gallium-68 (Ga-68)-labeled prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) tracer. This tracer targets the tumor and provides a precise location of the tumor, thereby improving diagnostic accuracy. "It should also help with prognostic stratification and biopsy planning and needle guidance," he said.

The radiotracer used also helps determine whether to image simultaneously or sequentially, according to Schlemmer. If the radiotracer is slowly taken up, then it's feasible to inject the tracer and image with PET followed by MRI, and later fuse the images. However, he noted that if the tracer is rapidly taken up or if, for example, there are moving organs (such as lung or liver), then there were often difficulties.

"When you conduct a PET and then transfer the patient to the MR scanner there is often a misrepresentation due to blurring without precise overlap," he said, noting that this had implications for tumor biopsy or tailoring radiotherapy to a precise location. "For these types of tumor, the combined PET/MRI is more suitable."

Schlemmer highlighted that PET/MRI also had implications in the treatment of oncologic patients, who usually require many repeat studies throughout the course of their disease, especially with cancer becoming a chronic disease. He cited the example of a patient with prostate cancer needing repeated imaging to monitor progression or treatment evaluation.

"In this situation, you want to minimize use of ionizing radiation to reduce harm and further cancer. We anticipate that PET/MRI use in these cases would reduce radiation exposure in these patients," he said.

However, it is still early days, and Schlemmer remarked that, to date, the clinical benefit has not been fully established. "We can only guess at this stage. There are no large multicenter trials providing evidence. However, our experience as oncologic radiologists is that we see the scope and applications."

He stressed that people need to remember how to assess costs associated with using PET/MRI. "Imaging is expensive, but therapy is also expensive. If you give the wrong therapy, then it is also very expensive for the patient too," he said. "We need to weigh up everything relating to clinical benefit and then conclude whether it is cost-effective or not. This can only be answered when it is integrated into the whole diagnostic and therapeutic process in oncologic imaging. We need to move beyond just asking if PET/MRI is better than PET/CT or MR alone."

Dr. Osman Ratib from Geneva. Image courtesy of the European Society of Radiology.

Dr. Osman Ratib from Geneva. Image courtesy of the European Society of Radiology.

Also speaking at the session was Dr. Osman Ratib, chairman of the department of radiology and head of the division of nuclear medicine at the University Hospital of Geneva in Switzerland. After Ratib's and Schlemmer's talks, an audience member from the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne, Australia, asked a pertinent question about whether PET/MRI would be better directed to regional assessments rather than whole-body assessments.

Ratib pointed out that they wanted the best of both worlds (whole body and regional), but that the cost for this was time.

"We would love to have whole screening and regional, but that is not very practical. We want to know if we should apply PET/MRI if we have a specific question and specific body area to examine. Maybe this is where PET/MRI is the best solution but right now, PET/CT remains a good technique for screening and whole-body scanning because it is fast," he pointed out. "We realize now that whilst we are desperate for whole-body MR because it is high-quality, it comes at the cost of the study, often taking more than an hour."

Schlemmer said that it was a matter of workflow. When you do PET imaging you always do whole-body assessment. You might then decide during the examination that you need a high-resolution or functional imaging studies. But he cautioned that tumors are always multifocal and often in unexpected areas.

"You only do the separate imaging in one body part when you have shown that the tumor has not spread elsewhere," he said.

Originally published in ECR Today on 10 March 2013.

Copyright © 2013 European Society of Radiology