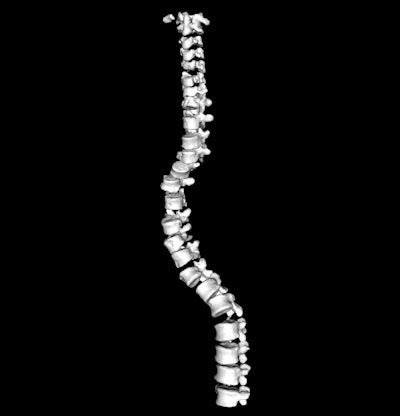

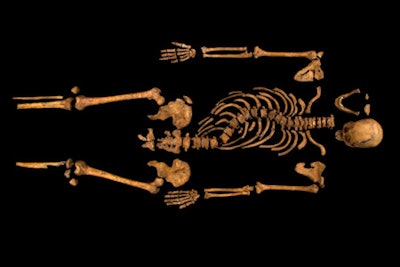

In the latest revelation relating to the discovery of the skeleton of King Richard III of England, a 3D printed reconstruction of his spine based on CT data confirms he suffered from the spinal condition scoliosis, although he wasn't quite the "hunchback" as portrayed by writers, including Shakespeare, over the centuries.

The reconstruction provides evidence that Richard III's spine had a scoliosis of around 70° representing the Cobb angle as measured clinically.

"We believe the scoliosis was around T9 [ninth thoracic vertebra] and the flex was between 60° to 80°. This is exactly what one would expect for a juvenile idiopathic scoliosis," said Dr. Bruno Morgan, a forensic radiologist in the University of Leicester Department of Cancer Studies and Molecular Medicine, who conducted the imaging aspects of the most recent study that specifically examined and physically reconstructed the spine of Richard III, speaking to AuntMinnieEurope.com.

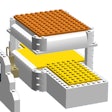

A 3D model of the spine with replica polymer vertebrae was created by laser sintering. All images copyright of the University of Leicester.

A 3D model of the spine with replica polymer vertebrae was created by laser sintering. All images copyright of the University of Leicester.The discovery of the king's skeleton was made in 2012 by a team from the University of Leicester in the U.K., and investigational work on the bones has been ongoing ever since. DNA evidence supports the fact the bones are "beyond reasonable doubt" those of King Richard III, according to the dig's leading archeologist, Richard Buckley.

The latest paper, titled "The scoliosis of Richard III, last Plantagenet King of England: Diagnosis and clinical significance," was published in Lancet on 30 May. It provides for the first time a complete picture of the scoliosis that plagued the king, who died at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. Morgan was the study co-author, while Jo Appleby, PhD, an osteoarcheologist also at the University of Leicester, was the study lead.

Morgan also worked closely with Dr. Guy Rutty, a professor at the East Midlands Forensic Pathology Unit, who conducted the initial forensic identification work in 2012. Scientists at the University of Loughborough played a central role in the process of 3D printing and reconstruction.

Unlike regular CT scanning, which provides an image of bones otherwise hidden beneath body tissues, the bones of Richard III were clearly visible with the naked eye.

Dr. Bruno Morgan (right) and Dr. Piers Mitchell with their 3D model.

Dr. Bruno Morgan (right) and Dr. Piers Mitchell with their 3D model."It is reasonable to ask what can be gained by scanning the bones," Morgan asked. "You can work out that there's a scoliosis. We believe that how we found him was how he went into the ground, without a coffin."

Because the king was 32 years old when he died, his scoliosis was relatively fixed with ligamentous ossification, Morgan noted. He showed a particularly pronounced right-sided curve that was spiral in nature. His right shoulder would have been higher than his left, and his torso would have been relatively short compared with his arms and legs. It is unlikely that Richard III had an overt limp, the authors added.

The finding clarifies the extent of the king's deformity. History and literature make reference to Richard III as severely disabled and "hunchbacked," but examination of the bones reveals a less severe spinal abnormality. The king's scoliosis was most likely to have developed from around the age of 10.

"If you saw Richard's bare back you would notice his right ribs stick out, a mild hunchback," Morgan said. "This is consistent with the historical records of the period."

CT scanning allowed the researchers to assess the images without touching the bones.

Reconstructed image from the CT scan of spinal vertebrae.

Reconstructed image from the CT scan of spinal vertebrae."Compared to a normal healthy bone, the density is very low, and, as a result, we avoid handling them too much. Gluing the bones together to figure out the angles would have caused serious damage," Morgan noted.

Radiology software to guide the reassembly of bones is relatively limited, so to reconstruct a replica spine, Morgan and the team at the University of Loughborough built a 3D printed model of the spine based on CT scan data using polymer material created at the Leicester Royal Infirmary.

"The magic of having the 3D printed model was that we actually had a structure we could play with and to help us figure out the nature of his spinal condition," Morgan said. The researchers could then determine how the condition affected Richard III's appearance.

King Richard's bones had experienced a damage-repair cycle causing degenerative remodeling, giving rise to the spinal curvature. Morgan decided to rebuild the spine from individual 3D model fragments, "to see what structure it took on." This would help determine whether the king's spine really had scoliosis, or whether his condition had possibly been a literary and historical exaggeration.

"I knew it was going to twist just by looking at it," Morgan remarked. "The lumbar disks were normal, so we allowed for normal disk space there, but the thoracic ones were degenerative so we thinned these down. Some of the facet joints had degenerative remodeling where they fitted together like a jigsaw. A steel wire held the vertebrae together, and fishing twine bound the facet joints and disk spaces."

Morgan deliberately avoided referring to photos of the body as he built the spine. "As I built it, it made an obligatory curve. I really couldn't have built it any other way," he said. "It completely agreed with photos of the body in the ground."

The skeleton of Richard III was discovered in a car park in 2012.

The skeleton of Richard III was discovered in a car park in 2012.Appleby, who carried out the initial excavation and analysis, said the replica polymer reconstruction provided a very accurate idea of the shape of the curve. "It's really good to be able to produce this 3D reconstruction rather than a 2D picture, as you get a good sense of how the spine would have actually appeared," she said.

The dig for Richard III was led by the University of Leicester in August 2012, working with the Leicester City Council and in association with the Richard III Society. The originator of the search project was Philippa Langley of the Richard III Society.

A Richard III Visitor Centre in the old Leicester Grammar School that overlooks the site of the dig is due to open in July 2014. There will be a mock-up CT scanner and replica bones. The actual bones of Richard III are due to be reinterred in Leicester's St. Martin's Cathedral in 2015.