CT has become a vital form of medical imaging that is ubiquitous throughout the world, offering powerful insights into the human body. Most of the credit for the development of CT goes to Sir Godfrey Hounsfield, the U.K. scientist who developed the first CT scanner in 1971.

A native of Nottinghamshire, U.K., Hounsfield was born on 28 August 1919 to a family of modest means. Having parents who were farmers, Hounsfield took full advantage of the space and freedom that a farm afforded a boy who was the youngest of five children.

Clearly imaginative and curious, Hounsfield constructed a homemade glider and said he used to launch himself from haystacks, his not-so-safe way of investigating principles of aviation. Indeed, his family offered encouragement with respect to the pursuit of scientific experimentation.

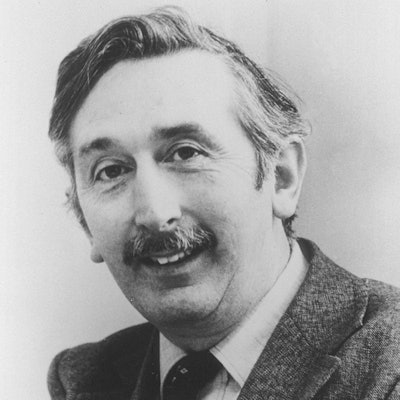

Sir Godfrey Hounsfield. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Sir Godfrey Hounsfield. U.S. National Library of Medicine.Despite his natural inquisitiveness, Hounsfield was not a stellar student and did not pursue formal higher education. He had a hands-on understanding of engineering, however, and began working in the drawing office of a local builder.

When World War II broke out, Hounsfield joined the Royal Air Force (RAF). There, he had the opportunity to learn about radio mechanics and became a radar mechanics instructor. His first posting was to the Royal College of Science in South Kensington in the U.K. (now part of Imperial College London). While in the RAF, he rose to the rank of corporal.

One of the senior officers in the RAF took notice of Hounsfield's abilities and facilitated, through a grant, his study after World War II at Faraday House Electrical Engineering College in London, where he received a diploma in electrical engineering.

The next significant step in Hounsfield's career was in 1951, when he began working at U.K. industrial conglomerate Electrical and Musical Industry (EMI) Limited. EMI was perhaps best known as the record label of the Beatles (the connection led to speculation that revenues from Beatles record sales funded development of the first CT scanner, a claim that most experts believe is apocryphal).

Hounsfield would have a long career at EMI, starting with researching guided weapon systems and radar science. He was also interested in computers and led the design of a commercially available all-transistor computer called EMIDEC 1100, which was released in 1959.

The genesis of CT

In 1967, Hounsfield's supervisors at EMI gave him the time to ponder any research projects that he had in mind to pursue. He then informed them of his idea to develop a device that would gather x-rays of an object from various angles and put them together into a 3D representation, with a goal to assist physicians to see the inside of the human body.

Hounsfield received a grant from the British government to pursue the research. He collaborated with two radiologists, Dr. James Ambrose and Dr. Louis Kreel, who assisted him in understanding the principles of radiology. They also provided tissue samples and test animals for experimental scanning.

Their investigations also built on the work of Allan MacLeod Cormack, PhD, a physicist from South Africa who published pioneering papers on the theory behind CAT scanning in 1963 and 1964 while at the University of Cape Town.

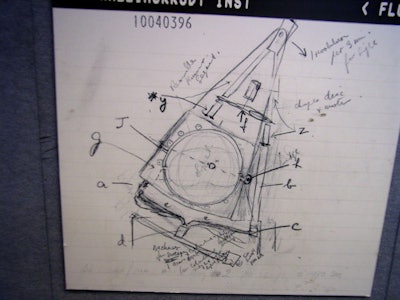

Original sketch from Hounsfield's notebook outlining the principles of CAT scanning. Image licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Original sketch from Hounsfield's notebook outlining the principles of CAT scanning. Image licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.These initial efforts were limited by the technology of the time: U.K. radiology historian Dr. Adrian Thomas notes that the first images of phantoms took nine days for acquisition and 15 minutes of computing time for reconstruction. But it wasn't long before Hounsfield's team had designed and constructed a prototype CAT scanner for the head. He tested the machine first on a cadaver, then on a cow brain from a butcher's shop, then on himself.

A head CAT scanner was soon installed at Atkinson Morley Hospital in London, where the first scan was acquired on a human patient on 1 October 1971, with the successful imaging of a patient with a cerebral cyst. A 1-cm slice could be acquired in about four minutes, Thomas notes; data had to be transferred via magnetic tape to an EMI lab nearby for reconstruction into images.

The results of these efforts were presented at the annual congress of the British Institute of Radiology in 1972 in a paper by Hounsfield and Ambrose. This was followed by coverage in the mainstream press, with the Times of London reporting on their paper on 21 April 1972.

The first clinical CAT scanner, installed at the Atkinson Morley Hospital in South London on 1 October 1971. Image courtesy of Dr. Adrian Thomas.

The first clinical CAT scanner, installed at the Atkinson Morley Hospital in South London on 1 October 1971. Image courtesy of Dr. Adrian Thomas.CAT (it was soon renamed CT) became a very effective diagnostic tool, particularly because of its ability to diagnose structural lesions in the brain. It replaced more invasive techniques like pneumoencephalography or carotid angiography, which had been used to visualize cerebral pathology.

As with most new technologies, early concerns were expressed about the cost of this new tool to the medical system. But the value of CT soon became apparent even to skeptics as it demonstrated its superiority over conventional x-ray for a variety of clinical applications.

Continued developments

Now heading EMI's medical systems section, Hounsfield continued to improve the scanning technology by reducing radiation exposure, sharpening the images, and developing larger scanners that could image other parts of the body. Hounsfield continued to innovate in the area of scanning at EMI, such as a full-body CT scanner.

In the 1980s, he became a consultant to an EMI research laboratory where he worked to refine the CT scanner and develop a model that could capture an accurate image of the heart. Subsequently, he focused on what was termed nuclear magnetic imaging, now referred to as MRI.

Later in life, Hounsfield became the recipient of numerous awards for his accomplishments, the most notable being the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1979, an honor he shared with Cormack.

Hounsfield was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1976 and knighted in 1981. He also received an honorary doctorate degree from the City University of London, among other recognitions.

Apart from being a major innovator in science, Hounsfield was a jazz musician, cinephile, and illustrator. A well-rounded individual, he enjoyed skiing, hiking, and playing the piano, which he taught himself to do.

Hounsfield died in London on 12 August 2004 at the age of 84, just two weeks short of his 85th birthday. He never married and had no children.

In his will, Hounsfield stipulated that there be a donation to the British Institute of Radiology to maintain an annual lecture in his name; the first Godfrey Hounsfield lecture was delivered in 1997. Another illustration of his legacy in radiology is the Hounsfield unit (HU), a measure of CT attenuation.

With all that Hounsfield accomplished, he has been described as a self-taught diagnostic revolutionary by some. Undoubtedly, Hounsfield's invention of CT has been indescribably significant to radiology as it has revolutionized medical diagnosis.

While Hounsfield was not classically educated and was not born of economic privilege, these barriers did not impede his scientific pursuits. His imagination and drive for scientific discovery knew no bounds. For that, the radiology community will be eternally grateful.

Further Reading

Godfrey N. Hounsfield, Biographical, Nobel Prize website.

50 years of CT scanning approaches, AuntMinnieEurope.com

Godfrey Hounsfield, Wikipedia

Godfrey Newbold Hounsfield (1919-2004): The man who revolutionized neuroimaging, Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology. 2016, Vol. 19:4, pp. 448-450.

Proceedings of the British Institute of Radiology. Annual Congress, 1972, British Journal of Radiology.

1970s radiology, British Institute of Radiology.

Godfrey Hounsfield: Intuitive Genius of CT. British Journal of Radiology, 2012.