It's hard to imagine that it's almost 50 years since the first clinical CT scan was performed. There can be few people in medical practice now who remember working before CT scanning.

The CT scanner -- or EMI scanner as it was initially termed -- was announced in 1972, which was the year that I entered medical school in London. During my placement with EMI, the British transnational conglomerate, I visited the National Hospital for Nervous Diseases in Queen Square, and I was thrilled to see the new scanner and its revolutionary images.

I remember the sense of excitement in the air over the huge potential of the new scanner. The new scanner was essentially the most important development in radiology since Wilhelm Röntgen radiographed his wife's hand in 1895. Seeing the scanner was a major reason why I chose radiology as a speciality.

The first clinical CT scanner was installed at the Atkinson Morley Hospital in South London on 1 October 1971. All images courtesy of Dr. Adrian Thomas.

The first clinical CT scanner was installed at the Atkinson Morley Hospital in South London on 1 October 1971. All images courtesy of Dr. Adrian Thomas.By modern standards, the scanner was slow and primitive. But at the time, it was leading edge technology. The images were obtained on the scanner and were printed onto hard copy (Polaroid Land Camera prints). The images could be either viewed on the scanner or on prints. It was also possible to purchase an independent viewing console to view the images. It should be remembered that these were long before the days of picture archiving and communication systems (PACS).

Link to the Beatles?

In the 1960s, Godfrey Hounsfield was working at EMI in Hayes, Middlesex, U.K., and he was interested in pattern recognition. He considered a closed box with an unknown number of items inside that could be looked at from multiple directions using a radiation source and a radiation detector. The results of the transmission readings could then be analyzed by a computer and presented as a slice in a single plane.

A widely held view is that the profits from the Beatles, the rock band, funded the scanner research. This is an urban legend, and there is no evidence for it. EMI Music did not fund EMI Medical.

Hounsfield developed a mathematical approach in a process of reconstruction. The original apparatus resembled that used by Allan MacLeod Cormack and was a simple lathe holding the object to be examined. The early experiments used Perspex phantoms of varying complexity. Shown below is an image from an album by Godfrey Hounsfield. Scanned directly from the original Polaroid photograph, it was labeled by Hounsfield and is the first CT image taken by him. It took nine days to take the picture and 15 minutes of computing time to reconstruct.

Polaroid image of the first CT scan made by Godfrey Hounsfield of a Perspex phantom.

Polaroid image of the first CT scan made by Godfrey Hounsfield of a Perspex phantom.Following the use of Perspex phantoms, a section of human brain in a Perspex box was examined. Most of the pictures from the lathe bed were scanned in 1969 and 1970. The original lathe bed apparatus may be viewed in the library of the British Institute of Radiology in Portland Place in London.

The prototype scanner was installed at Atkinson Morley's Hospital in Wimbledon, South London, on 1 October 1971, under the supervision of the neuroradiologist James Ambrose. This prototype scanner looks very similar to modern CT scanners and is currently on display in the Science Museum in South Kensington in London.

It took four minutes to obtain each slice, with a slice thickness of about 1 cm. The prototype scanner purely acquired data with no computer attached for data processing. The data was transported on magnetic tape to the EMI Central Research Laboratories in nearby Hayes. The data were reconstructed using an International Computers Limited (ICL) 1905 mainframe computer and the image had an 80 x 80 matrix and took 20 minutes to reconstruct.

The software was written by Stephen Bates, who made major contributions to the early CT computing at EMI. It would have been possible to have reconstructed the data using a 160 x 160 matrix, but that would have taken considerably longer and was not attempted. Ambrose felt that six months of work was necessary to build up an experience of both the normal and abnormal.

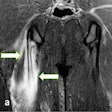

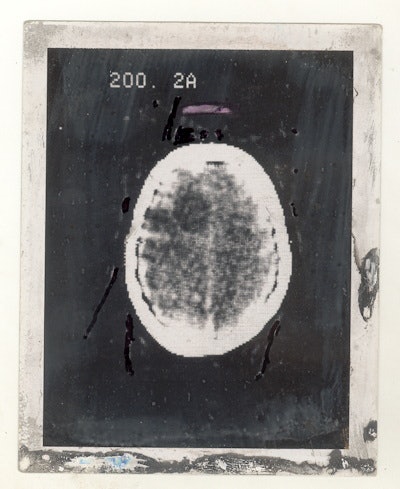

The first patient scanned on the new machine was a 41-year-old woman with a possible frontal lobe tumour. The results were returned to Ambrose after two days. A cystic tumour in the left frontal lobe (viewed from above) was shown clearly, and Ambrose said that on seeing the images, he jumped around with Hounsfield like football players who had just scored a winning goal (Bates, 2012).

Polaroid image of the first clinical CT scan shows a large cystic lesion in the left frontal lobe.

Polaroid image of the first clinical CT scan shows a large cystic lesion in the left frontal lobe.The preliminary results were presented at the Annual Congress of the British Institute of Radiology in April 1972. The paper presented by Ambrose and Hounsfield was entitled "Computerised axial tomography (A new means of demonstrating some of the soft tissue structures of the brain without the use of contrast media)." As might be expected, the paper produced a sensation and the first press announcement was in the Times of London on 21 April 1972.

The first paper by Hounsfield (Hounsfield 1973) described the technical background, the second paper was by Ambrose (Ambrose 1973) and described the clinical findings, and the third paper by Perry and Bridges (Perry, 1973) looked at radiation doses.

Brochure cover for the EMI 1010 scanner, signed by Godfrey Hounsfield.

Brochure cover for the EMI 1010 scanner, signed by Godfrey Hounsfield.EMI then started the production of a brain machine and made five: one for the National Hospital in Queen Square, one for Manchester, one for Glasgow, and two for the U.S. (Mayo Clinic and Massachusetts General Hospital). All machines were installed in the summer of 1973. James Bull from Queen Square described the new machine to Dr. Fred Plum, a leading American neurologist. Plum said that U.S. would need at least 170 brain machines to cover the neurology departments and that it would soon become unethical for a neurologist to practice without access to a brain machine, since it saved many patients from unnecessary suffering from the currently available techniques.

Radiology was changed forever by the CT scanner. There is no monument to Godfrey Hounsfield, but it can be said that the CT scanner and the benefits to patients that it resulted in is the only monument that he desired.

Further Reading

Ambrose J. Computerized transverse axial scanning (tomography). Part 2. Clinical application. Brit J Radiol. 1973;46:1023-1047.

Bates S, Beckmann E, Thomas AMK, Waltham R. 2012. Godfrey Hounsfield: Intuitive Genius of CT. The British Institute of Radiology: London.

Hounsfield GN. Computerized transverse axial scanning (tomography). Part 1. Description of system. Brit J Radiol. 1973;46:1016-1022.

Perry BJ, Bridges C. Computerized transverse axial scanning (tomography). Part 3. Radiation dose considerations. Brit J Radiol. 1973;46:1048-1051.

Dr. Adrian Thomas. Image courtesy of the BIR.

Dr. Adrian Thomas. Image courtesy of the BIR.Dr. Adrian Thomas is chairman of the International Society for the History of Radiology and honorary historian at the British Institute of Radiology.

The comments and observations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions of AuntMinnieEurope.com, nor should they be construed as an endorsement or admonishment of any particular vendor, analyst, industry consultant, or consulting group.