Women who attend organized breast cancer screening have a higher survival rate than women who attend opportunistic screening, according to a French study published on 9 December in Cancer Epidemiology.

Researchers led by Marie Poiseuil from the University of Bordeaux, however, also found that women who attend both screening types have a significantly higher survival rate than women who do not participate in any such screening, especially those underserved by the healthcare system.

"This finding was more marked among the most [economically challenged] women," Poiseuil and co-authors wrote. "Thus, it seems important to raise awareness of organized screening by showing the net survival gain after breast cancer, regardless of level of deprivation."

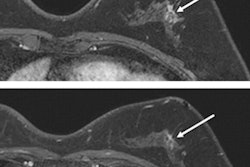

Organized breast screening in France targets women between the ages of 50 and 74 who do not have a high risk of breast cancer. These women undergo screening every two years. Despite European recommendations and targets set at 70%, participation in such organized screening was only 48.6% in France in 2019.

Opportunistic screening is when mammograms are ordered and performed at the request of the general practitioner, gynecologist, or patient. Usually, high-risk women undergo this type of screening. However, it can also be done in women with no clinical indications or proven risk factors. Tracking participation in opportunistic screening is more difficult, the researchers noted.

In a previous study, Poiseuil and colleagues showed that women whose cancer was diagnosed through organized screening had a higher five-year net survival than women whose cancer wasn't discovered on screening, and this was regardless of social inequalities. However, survival rates in nonattenders decreased with increasing poverty.

For this study, the researchers wanted to estimate one- and five-year net survival among women with breast cancer, according to their screening type. They also took levels of economic challenge into account, using a scale of one through five (with one equal to the most affluent women in the study and five representing the poorest). The research included 14,208 women from three French centers; among these, 75% participated in organized screening, 10% opportunistic screening done, and 15% had not been screened at all.

Poiseuil's group found that net survival at five years was 97% for the organized screening cohort, 94.1% for the opportunistic screening group, and 78.1% for the nonattendee group.

Socioeconomic analysis showed that five-year net survival probabilities were over 96% in each quintile of the organized screening group but that there was no difference in survival in this group according to the level of economic resources.

But decreases in survival rates were seen in the opportunistic screening and nonattendee groups as poverty levels increased, with survival probabilities decreasing from 97.4% to 90.5% depending on affluence.

The differences in survival according to level of socioeconomic deprivation could be due to several factors, the researchers noted, including lower health knowledge among women in opportunistic screening, more complicated access to care, poorer care in poorer areas, and less cancer post-treatment follow-up.

"Moreover, differences in survival are also usually explained by tumor characteristics, but this seems to be better controlled by screening than by care to explain the difference among deprived women," they noted.