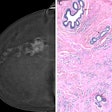

Interval breast cancers -- those found between mammography screenings -- are more likely to be aggressive, fast-growing tumors, according to a Canadian study of more than 430,000 women that was published online May 3 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Interval cancers include tumors that were visible but missed on a mammography image due to technical or interpretive reasons; known as missed interval cancers, these comprise 25% to 35% of the group. Interval cancers also include those that were not mammography detectable at the time of screening. This category, true interval cancers, makes up the remaining 65% to 75%.

The study, from the Cancer Care Ontario in Toronto, was designed to compare tumor characteristics of true and missed interval cancers with matched screen-detected breast cancers of participants in the Ontario Breast Cancer Screening Program, a large population-based program. Lead researcher Anna Chiarelli, PhD, from the center's department of prevention and cancer control, and colleagues hypothesized that interval breast cancers would differ by prognostic features when compared with cancers detected at screening.

During the eight years of the study, the mammography screening program offered biennial mammography screening exams to eligible women 50 years of age and older living in the province of Ontario. Women identified as high risk had annual mammograms. Women were excluded from the study if they had undergone breast augmentation, had symptoms of breast disease, or had a history of breast cancer.

The patient cohort consisted of 431,480 women, in whom a total of 3,862 cancers were diagnosed from mammograms performed between January 1, 1994, and December 31, 2002. In all, 616 interval cancers were identified, of which 462 (75%) were classified as true interval cancers, 146 (23.7%) as missed interval cancers, and eight (1.3%) as unclassifiable.

The researchers matched two screen-detected cancers for each missed interval cancer according to the following criteria: region of screening center, within five years of age, and within five years of last screening mammogram. The same criteria were used to match one screen-detected cancer with each true interval cancer. In total, 798 screen-detected cancers were selected as potential matches.

The analytic sample ultimately included 87 missed interval cancers, 288 true interval cancers, and 450 screen-detected cancers. Current hormonal therapy use, previous diagnosis of benign breast disease, and a mammographic density of 75% or greater were more prevalent among women diagnosed with an interval cancer.

"Compared with matched screen-detected cancers, interval cancers were larger, of more advanced stage, more poorly differentiated, more likely to have lymph node involvement, and had a higher proliferative rate," Chiarelli and colleagues wrote.

The researchers also determined that women with missed interval cancers had an increased risk of nodal involvement, and almost 30% of true interval cancers had a high mitotic index, compared with only 11% of cancers detected during a routine mammogram. In addition, a higher percentage of heterogeneous tumors, including tubular and mucinous carcinomas, were associated with true interval cancers.

The group attributed the aggressive tumor features found in interval cancers to rapid proliferation rates, delays in diagnosis, and partially reduced tumor detection on mammograms.