The dates of Guido Holzknecht (1872-1931) closely match those of fellow Viennese Adolf Loos (1870-1933), a pioneer of modernist architecture. Both men transformed their respective disciplines, and both made us look at the world differently.

Holzknecht was introduced to x-rays by Vienna's first radiologist Gustav Kaiser (1871-1954). In 1899, Holzknecht was offered a position working in the department of Hermann Nothnagel (1841-1905), a professor of medicine in Vienna. Holzknecht set to work, and he particularly devoted himself to the study of the chest.

His first major observation was on bronchial obstruction; he made the classic observation that the mediastinum shifted on expiration secondary to the air-trapping. He made measurements of the cardiac contour, and emphasized the usefulness of the oblique views when looking at the aorta and the esophagus.

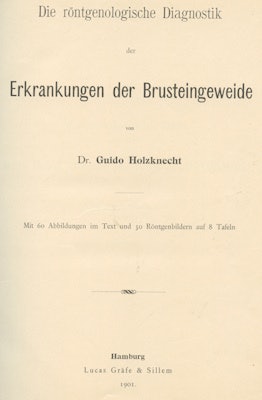

Fig. 1: Guido Holzknecht. Die röntgenologische Diagnostik der Erkrankungen der Brusteineweide (1901).

Fig. 1: Guido Holzknecht. Die röntgenologische Diagnostik der Erkrankungen der Brusteineweide (1901).On the basis of this work, in 1901 he published the first book devoted to radiology of the chest (Fig. 1). This is a wonderful book, and bearing in mind its early date and primitive apparatus, the quality of the images is remarkable and it is one of the great books in radiology.

The famous French radiologist Antoine Béclère considered this work to be on the same level of importance as the Traité de l'ausculation mediate of René Laennec, which described the stethoscope. My teacher, cardiac radiologist Robert Steiner, thought, "It is incredible how accurate this particular observer has been in the interpretation of cardiac contours."

Sadly, in 1901 Gustav Kaiser was forced to retire due to his developing radiodermatitis. Kaiser was to live until 1954, but Holzknecht was not to be so fortunate.

So why is this book so important? It's not just that it was the first book devoted to chest radiology, but also it's the quality of his work. The book is illustrated with line diagrams that show he was aware of the principles involved in radiography.

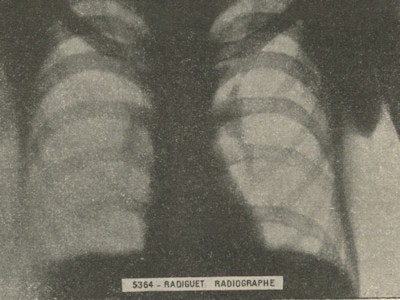

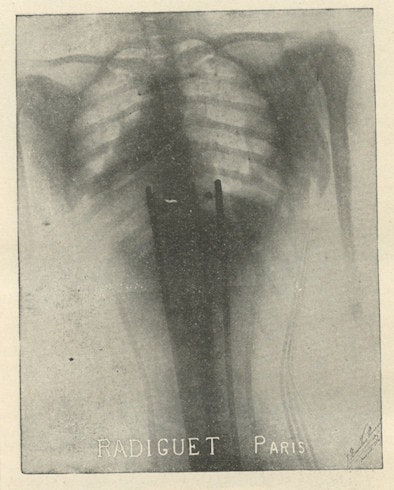

Fig. 2: Chest radiograph (1901).

Fig. 2: Chest radiograph (1901).Holzknecht reproduces radiographs (Fig. 2) and also a series of line diagrams. Whilst his apparatus looks primitive to us today, it was the high-tech equipment of his time (Fig. 3). As can be seen, there is an absence of protection, with no shielding around the x-ray tube seen centrally, and also no protection around the fluorescent screen.

Fig. 3: Apparatus used by Guido Holzknecht in 1901.

Fig. 3: Apparatus used by Guido Holzknecht in 1901.The operator would be exposed to both primary and secondary radiation, and this is why there were so many injuries in this first generation of radiologists. There was also the pernicious habit of using one's own hand to test the quality of the x-ray beam.

Fig. 4: The early use of a cross-sectional image.

Fig. 4: The early use of a cross-sectional image.The significant use of cross-sectional images to illustrate the principles of radiography is fascinating (Fig. 4). Holzknecht would have loved modern CT scanning! He also made radiographs of the heart as a specimen to aid his understanding of cardiac anatomy at radiography.

There is an interesting image of a pyo-pneumothorax, which was common at that time and presumably related to the blind puncturing of the chests in cases of suspected empyema. A particularly interesting image is one of a young lady wearing a corset, showing the harmful effects of the contemporary fashion for women (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5: Radiograph of a young woman wearing a corset.

Fig. 5: Radiograph of a young woman wearing a corset.As was the case in those days, Holzknecht was interested in both diagnosis and therapy, and in 1902 he described his well-known chromoradiometer, which was the first device designed to measure radiation dose. This was a major advance.

In addition, Holzknecht was probably the first person to suggest that radiology should be a medical specialty in its own right. In 1903, along with his Viennese colleague Robert Kienböck, he proposed that there was more to radiology than just simply the use of a helpful technique.

He was actively involved in the training of young radiologists and emphasized the need for radiologists in training to be familiar with physiology, anatomy, and pathology, as well as the clinical features of the disease, in order to make an accurate and helpful radiological diagnosis. The Viennese school of radiology became hugely influential and attracted many foreign students. Holzknecht was also the first to describe gastric cancer using radiology.

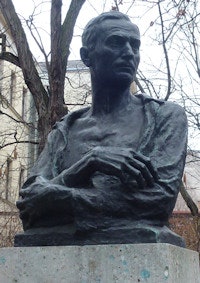

Fig. 6: Statue of Guido Holzknecht in the Arne Karlsson Park in Vienna.

Fig. 6: Statue of Guido Holzknecht in the Arne Karlsson Park in Vienna.There is a statue of Holzknecht in the Arne Karlsson Park in Vienna (Fig. 6). It's well worth a visit when you are next at the ECR. There is poignancy about the figure, with his poor damaged hands held in front of him.

Antoine Béclère said of Holzknecht that, "No one brought more passionate ardor and inspiration to the pursuit of a good and high ideal, no one had a deeper zeal, was more indefatigable, had more courage, dedication or selflessness."

As we remember this amazing pioneer, may we all have a similar dedication in our daily service to our patients.

Dr. Adrian Thomas is chairman of the International Society for the History of Radiology and honorary librarian at the British Institute of Radiology.

This article was first published by AuntMinnieEurope.com on 13 May 2014.

Further reading

- Del Regato, JA. Radiological Oncologists: The Unfolding of a Medical Specialty. American College of Radiology; 1993.

- Holzknecht, G. Die röntgenologische Diagnostik der Erkrankungen der Brusteineweide. Hamburg: Lucas Gräfe & Sillem; 1901.

- Steiner, RE. The Impact of Radiology on Cardiology. BJR. 1973;46(550):741-753.

The comments and observations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions of AuntMinnieEurope.com, nor should they be construed as an endorsement or admonishment of any particular vendor, analyst, industry consultant, or consulting group.