A Dutch study has found that MRI screening can detect invasive breast cancers about six years earlier than mammography. The findings, based on first- and second-round invasive cancer detection rates, were presented at the annual meeting of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM).

"The central question for breast cancer screening is which modality is the best to supplement or replace mammography for routine screening for breast cancer," Keith Cover, PhD, an independent researcher from Amsterdam told AuntMinnieEurope.com.

The Breast Screening - Risk Adaptive Imaging for Density (BRAID) clinical trial should help to answer this question. The sensitivity of the modalities being considered -- 3-tesla MRI, 1.5-tesla MRI, contrast-enhanced mammography, and ultrasound -- has a critical role in any outcome, he explained.

How 'the sieve model' works

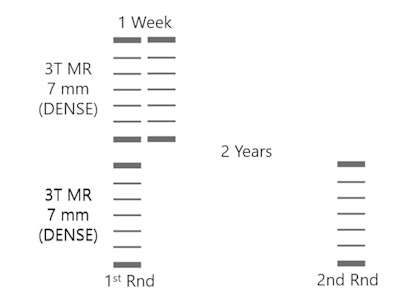

In a poster at ISMRM 2022 in May, Cover proposed "the sieve model" to represent the performance (sensitivity) of a screening method -- i.e., the modality combined with its implementation details.

The technique demonstrates that the performance of a method can be characterized by the size of the breast cancers it detects in later rounds. A method that detects smaller cancers is more likely to detect them earlier and yield a better patient outcome. With application of the sieve model, it is assumed that the type of patients being screened -- dense breast, extremely dense breasts, familial, etc. -- will only have a minor impact on the size of cancers detected with a screening method, he noted.

This finding is also consistent with the Dense Tissue and Early Breast Neoplasm Screening (DENSE) trial, a randomized, controlled trial to study the effect of supplemental MRI on the incidence of interval cancers in women with extremely dense breast tissue.

Sieve model of breast cancer screening for the two-year interval of the second round of the 3T MRI DENSE trial compared with a hypothetical model with only one week between screens. Courtesy of Keith Cover, PhD.

Sieve model of breast cancer screening for the two-year interval of the second round of the 3T MRI DENSE trial compared with a hypothetical model with only one week between screens. Courtesy of Keith Cover, PhD.The DENSE trial found MRI screening-detected breast cancers 14 times smaller in volume than mammography -- a reduction in median cancer size from 17 mm to 7 mm. The trial also found the interval cancer rate reduced from 5 per 1,000 for mammography to 0.8 per 1,000 for MRI screening. Both these results strongly suggest a much better outcome for patients who have their cancers detected with MRI screening, although some experts believe five to 10 years of follow-up will be needed to confirm this promising outcome, Cover explained.

The DENSE trial used "prior" first-round exams to estimate lesion growth over the two years between rounds, and it found a high false-positive rate in the second round. The high false-positive detection rate of MRI screening is one of the main reasons the much earlier detection of breast cancer with MRI screening is not widely available.

"The 'how much earlier' measure provides an additional means for comparing the relative performance of breast cancer screening modalities," he said. "The big surprise of my research is that a large part of the data needed to answer the central question currently facing screening for breast cancer may already be available, instead of being years away."

More research is needed to confirm if the detected cancer size does provide a defining characteristic of each breast cancer screening method, but if the hypothesis does hold up, it could help advance by years the widespread availability of much more sensitive breast cancer screening, according to Cover.

Additional findings

The sieve model offers a simple explanation of why the MRI first-round cancer detection rate in the DENSE and the Familial MRI Screening (FaMRIsc) trials was several times larger than both mammography and the later MRI rounds -- this large excess of small cancers has often been attributed to "over diagnosis," he continued.

"One understanding is the second-round invasive cancer detection rate, to a good approximation, is the number of cancers that were created every two years. While the timing of cancer detection depends on the screening modality, the rate of creation is assumed to be constant over time," Cover said.

"A second understanding is the first-round invasive cancer detection rate is the number of cancers missed by mammography but detected by MRI. If the mammogram three months prior to each MRI had actually been an MRI, the rate would have been zero to within measurement error," he said.

A key simplification is assuming MRI's superior sensitivity is only because MRI can see smaller cancers than mammography, and mammography misses cancers only because they are too small for it. The approximations made -- such as no cancers detected as interval cancers during the study -- while not strictly correct, were reasonable. The differing sensitivity of MRI and mammography to different cancer types may need further examination, Cover added.

At about six years, the earlier detection by MRI of breast cancer than mammography provides another measure to compare the performance of the two breast cancer screening modalities. In addition, it may be possible to use the "how much earlier" measure to compare other modalities, he concluded.

In a personal declaration issued at ISMRM 2022, Cover noted he is the lead inventor of color intensity projection, a tool for displaying MRI time-to-enhancement maps in breast cancer. Also, Amsterdam University Medical Center is the assignee of the patent, and BrainLab is a licensee.