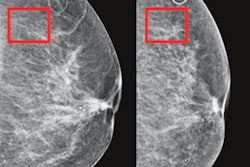

As screening mammography technology continues to improve, the detection of benign breast disease has increased -- making it all the more important that clinicians understand the factors that boost a woman's chances of developing these diseases, according to a Swedish study published on 25 June in JAMA Network Open.

A team led by Annelie Johansson, PhD, from the Karolinska Institute in Solna found that the risk of the most common benign breast diseases by hormonal factors was influenced by age, while family history of breast cancer was associated with the risk of proliferative and nonproliferative benign breast diseases.

"These findings suggest a heterogenous benign breast disease risk pattern by the traditional hormonal breast cancer risk factors and that the risk of benign breast diseases varies among the analyzed age groups," the authors wrote.

Benign breast diseases are common throughout a woman's lifetime, and they can be a concern for many women, the researchers said. But despite increasing detection of these diseases by population-based mammographic screenings, the cause and risk of benign breast diseases have not been extensively studied, Johansson and colleagues noted. Reproductive and lifestyle factors that affect hormonal exposure are understood to affect a woman's breast cancer risk, but little is known regarding these factors and benign breast diseases.

Johansson told AuntMinnieEurope.com there are several reasons behind benign breast diseases not being extensively researched, including that a diagnosis is not directly life-threatening and that there is a lack of good data enabling this type of study.

"The reporting of benign breast diseases is not as standardized as with other diseases such as cancer, nor is the classification of different subtypes of benign breast diseases," she said.

The study used data from 61,617 women in Sweden who underwent clinical mammography or attended mammography screenings at four Swedish hospitals from 2011 to 2013 to estimate incidence rates for distinct benign breast disease subtypes in individuals 25 to 69 years of age.

The authors found that incidence of benign disease varied by age and disease subtypes: Fibroadenoma, epithelial proliferation, and fibrocystic changes were relatively common at younger ages, increased during the 30s and 40s, and decreased afterward. Incidence of fibrocystic changes peaked at the age of 43 and epithelial proliferation and fibroadenoma at 46 years old.

They also noted that epithelial proliferation with atypia was less common at younger ages, with a maximum at 45 years old, and the incidence rates for cysts increased rapidly after age 40, with a maximum age of 50. Premenopausal women without children had reduced risk of epithelial proliferation without atypia, but increased risk of cysts.

Current and long oral contraceptive use (i.e., eight years or more) were associated with reduced premenopausal risk of fibroadenoma, whereas hormone replacement therapy was linked with increased postmenopausal risks of epithelial proliferation with atypia, fibrocystic changes, and cysts.

In any case, understanding the factors that contribute to benign breast disease could translate to better communication when it's discovered on screening mammography.

"We are further interested in understanding the differences between women diagnosed with multiple benign breast diseases, as well as continue to study the link between lifestyle factors, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity, and the risk of benign breast diseases," Johansson said.