Researchers from France discovered a thyroid cancer screening technique that hit all the right notes. The method can noninvasively detect abnormally stiff tissues on ultrasound when participants sing the "eeee" sound, according to a study published on 12 January in Applied Physics Letters.

The ultrasound technique works because singing causes the elasticity of surrounding tissues to increase, making it easier for clinicians to pinpoint abnormally stiff areas. Singing during thyroid ultrasonography also has the potential to identify more thyroid tumors while simultaneously putting patients at ease.

"Developing noninvasive methods would reduce the stress of patients during their medical exams," stated lead author Steve Beuve, a doctoral student specializing in medical imaging at University of Tours, in a press release. "Having to sing during a medical exam can perhaps help release some of the nervous tension even more."

The authors called their new technique vocal passive elastography. The method was inspired by passive elastography, which detects changes in elasticity from natural vibrations caused by blood pulsing, heart rhythms, and other natural biological changes.

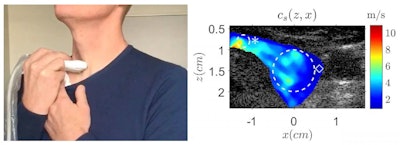

During vocal passive elastography, a clinician places a linear ultrasound probe at the front of a patient's neck. The patient then sings and maintains the "eee" tone, trying to match their tone to a 150-Hz sound playing from a speaker.

The singing vibrates the patient's trachea, which in turn produces vibrations throughout the thyroid. This allows the clinician to use an ultrafast frame rate to track changes in shear-wave velocity.

"The propagation of shear waves gives us information about mechanical properties of soft tissues," Beuve stated.

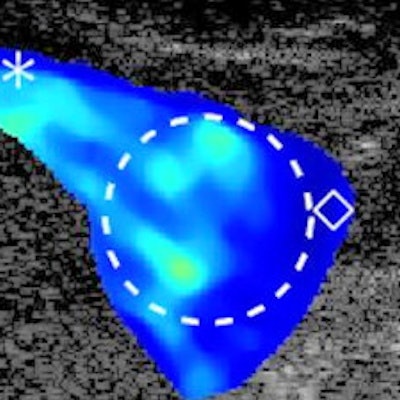

For their experiment, the team validated the concept by calculating shear-wave elastography (SWE) measurements as patients sang, then superimposing a map of that data onto B-mode ultrasound images. They created their own algorithm to reconstruct the raw image data and tested their algorithm on two different ultrasound systems.

The vocal passive elastography method succeeded in identifying particle tissue displacement induced by singing on both systems. The values also aligned well with SWE metrics, although the measurements were more similar on the left (thinner) side of the thyroid than on the right (thicker) side.

Left: A volunteer holds a linear ultrasound probe to help prove the feasibility of vocal passive elastography. Right: 2D shear wave speed as calculated by the new technique mapped onto an anatomical brightness mode ultrasound image. Image courtesy of Steve Beuve.

Left: A volunteer holds a linear ultrasound probe to help prove the feasibility of vocal passive elastography. Right: 2D shear wave speed as calculated by the new technique mapped onto an anatomical brightness mode ultrasound image. Image courtesy of Steve Beuve.Overall, vocal passive elastography looked like a promising alternative to fine-needle aspiration biopsy, which misses up to 95% of thyroid cancers, according to the authors. It also drastically improved the thyroid signal-to-noise ratio by drowning out natural background noise from nearby organs.

The researchers are already conducting new experiments to further refine the technique, including investigating the benefits of asking patients to match different bandwidths. They are also interested in expanding the use of vocal passive elastography to areas outside of the vocal tract, such as the brain.

"We want to cooperate with physicians to propose protocols to verify the relevance of elasticity as a biomarker of pathogens," Beuve stated.