An innovative approach to vascular procedures involving advanced imaging techniques and 3D printing is transforming training and practice at the Marie Lannelongue hospital in Paris. Performance and patient outcomes have improved dramatically, attendees learned at a webinar on 18 June.

"The problem when you perform complex cases is that it is difficult to train young vascular surgeons on humans. This is why we launched the 3D printing program a year ago and why we now have a model that is routinely used," said Prof. Stéphan Haulon, PhD, head of the hospital's aortic center and president of the European Society for Vascular Surgery.

The Marie Lannelongue specializes in cardiac, vascular, and lung procedures, and staff treat many of its patients with minimally invasive procedures for occluded arteries and dilated arteries (or aneurysms). These procedures are often complex and require an endograft designed for the patient's anatomy.

Adding 3D printing provides a new 'hands-on platform' for residents and fellows in training that wasn't available even just a few months ago, and cutting-edge training and preoperative planning based on 3D printing could improve surgical performance and patient outcomes, as supported by published data, according to Haulon.

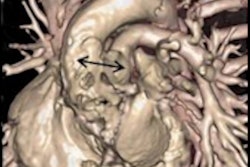

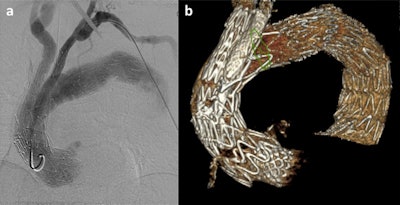

Haulon's team is working on new endografts for endovascular Bentall procedures. All images courtesy of Prof. Stéphan Haulon, PhD.

Haulon's team is working on new endografts for endovascular Bentall procedures. All images courtesy of Prof. Stéphan Haulon, PhD.The training comprises simulation sessions using tailor-made 3D anatomical models based on patient imaging data. On the model printed from the data, surgeons can practice the procedure specific to the individual patient several times over if need be and resolve potential issues that might arise before undertaking the real surgery.

"We want to know, prior to performing a case, where the anatomical challenges will be. If we can rehearse a complex case prior to doing it, then we will probably become better," he said.

In addition, younger residents can now practice surgical techniques and try out tools on lifelike models that resemble a real patient's anatomy in size, texture, and function. This can be particularly helpful for developing skills for exams such as the European Vascular Board examination. During the training, residents can stop and discuss certain points in a way that would not be possible during a real operation.

Teamwork and a hands-on approach are essential in endovascular simulation. (Photo taken before COVID-19 pandemic)

Teamwork and a hands-on approach are essential in endovascular simulation. (Photo taken before COVID-19 pandemic)"They will learn skills like how to navigate away from the aortic wall and how to manage radiation protection, and they will learn more about endovascular tools and be involved in the planning process," Haulon explained.

"We also know that simulation improves endovascular aortic repair (EVAR) outcomes. The literature shows that if you can train on such a model, you are going to reduce your fluoro time and procedure time, reduce the amount of contrast injected throughout the procedure, and be able to position the graft more accurately. You're going to become a much better vascular surgeon," he added.

Advanced imaging

Whether performing a complex or more straightforward procedure, surgical teams need x-ray guidance to position the endograft correctly in the patient's aortic anatomy, and advanced imaging techniques are being used in operating rooms that are now hybrid rooms combining the best of advanced imaging with the best of open surgery, Haulon continued.

Hybrid operating rooms at the Marie Lannelongue hospital combine complex surgery with advanced imaging systems.

Hybrid operating rooms at the Marie Lannelongue hospital combine complex surgery with advanced imaging systems.He pointed to fusion guidance being a way to have 3D guidance when registering the preoperative CT scan on top of the fluoroscopy image. This helps with accuracy, reducing exposure to radiation and using less contrast. Conebeam CT performed at the end of the procedure provides a 3D data set that doctors can use to check technical success -- if there are any issues, these can be fixed right away, he noted.

3D prints

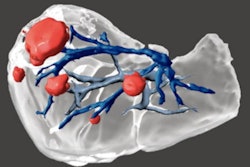

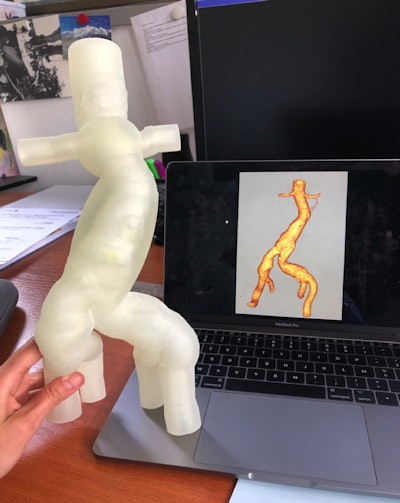

The hospital's first 3D-printed aorta was produced in 2019, and it was for a patient with an aortic iliac aneurysm. Following preoperative CT angiography, the surgical team sized the endograft and prepared the fusion mask for intraprocedural guidance, and then extracted the DICOM file of the aorta and converted it into an STL file, which is a format native to the stereolithography CAD software created by 3D systems. From this file, the model was printed. The first simulation was deemed similar to a classic procedure and much better than commercially available endovascular simulators, according to Haulon.

Besides the 3D aortic model, such an endovascular simulation requires a pulsatile pump with hot fluid and an imaging system.

The first 3D-printed aortic model produced at the Marie Lannelongue hospital.

The first 3D-printed aortic model produced at the Marie Lannelongue hospital.The printed models comprise three layers for strength and versatility, and the print needs to also include connectors. Weak points are strengthened by reinforcing balls to ensure no leakage.

Such models look and act just like real aneurysms, and each can serve as practice for 50 to 100 cases, Haulon told attendees, pointing out that the models have the same size aorta as the specific patient, the same pathology to the millimeter and simulated blood flow from the pulsatile pump.

He acknowledged the help of GE Healthcare, which organized the webinar, in finding the right partners to create reliable 3D prints. He also said his team uses the vendor's Advantage Workstation for a one-click export to obtain a 3D file within minutes, and this helps makes the process quick and simple.

Future projects

The hospital is building a new catalog based on specific and rare diseases encountered in practice, and these will serve to create models for training, Haulon said.

Prof. Stéphan Haulon, PhD.

Prof. Stéphan Haulon, PhD.He also underlined how such models would serve to assess new procedures and devices such as endografts to perform endovascular Bentall procedures (aortic valve, root, and ascending aorta repair). He refers to this as "the future minimally invasive surgery revolution."

"We want to develop new endografts and new procedures, and 3D prints can be helpful for [such] innovation," Haulon said. "Every time an emerging technology becomes available, we can test it. I become the trainee ... and can get familiar with any new technology, AI, virtual reality, before I actually use it on everyday cases."

"Now we have the perfect model and dedicated research environment to train our younger residents," he concluded.

You can access the full GE webinar via this web page.