U.K. researchers have used a single MRI brain scan and an automated tissue segmentation tool to predict cognitive problems in patients with stroke-related small-vessel disease in the brain. Their work may establish useful image-based biomarkers for small-vessel disease severity.

A hallmark of small-vessel disease is damage to tiny blood vessels in the brain caused by stroke and other diseases. Outwardly, patients with small-vessel disease may have problems in planning, organizing, and processing information quickly, although their memory functions often appear relatively stable. Others may develop dementia.

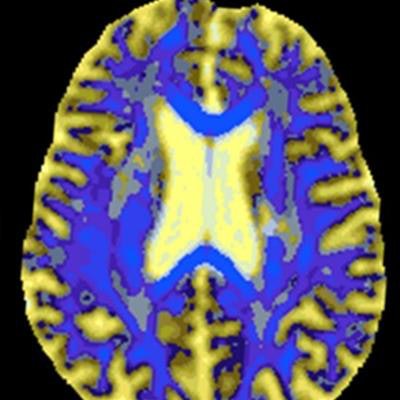

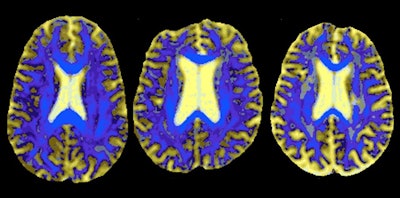

Axial diffusion-tensor image segmentation images of the reference brain (left), a stable small-vessel disease patient who did not progress to dementia (middle), and a patient who developed dementia during the study (right). Image courtesy of Williams et al, Stroke, October 2019, Vol. 50:10, pp. 2775-2782. CC license.

Axial diffusion-tensor image segmentation images of the reference brain (left), a stable small-vessel disease patient who did not progress to dementia (middle), and a patient who developed dementia during the study (right). Image courtesy of Williams et al, Stroke, October 2019, Vol. 50:10, pp. 2775-2782. CC license.While early treatment could help individuals at risk, identifying those who may go on to experience cognitive decline or dementia remains difficult.

"Our objective was to find a measure of brain tissue microstructural damage," said senior author Rebecca Charlton, PhD, a senior lecturer in psychology at Goldsmiths, University of London. "Using a new technique based on readily available MRI scans, we can predict which people go on to show cognitive decline and develop dementia."

In 2001, Charlton and her research team began investigating the use of an advanced MRI technique, diffusion-tensor imaging (DTI), to evaluate cerebral small-vessel disease, track disease severity, and identify individuals vulnerable to dementia and cognitive decline.

DTI is important when a tissue, such as the neural axons of the brain's white matter, has a fibrous structure. Water will diffuse more rapidly in the direction aligned with this structure and more slowly as it moves perpendicular to the preferred direction. To sensitize the MRI system to this diffusion, DTI techniques vary the magnetic field in the MRI equipment.

DSEG predicts cognitive decline

Unlike other MRI-based markers of brain damage in individuals with small-vessel disease, the diffusion-tensor image segmentation (DSEG) technique assesses brain microstructural damage from small-vessel disease using a single DTI acquisition at 1.5 tesla and automatic segmentation of the cerebrum. The researchers obtained MRI scans annually for three years and cognitive tests annually for five years for 99 individuals participating in the study.

DSEG maps the cerebrum into 16 segments. By comparing the segments of an individual with small-vessel disease to those of a healthy brain, the researchers derived a DSEG spectrum containing information about gray matter, white matter, cerebrospinal fluid, and regions with diffusion profiles that deviate from those of healthy tissue.

The researchers found that DSEG measures increased over time, indicating progression of small-vessel disease burden. DSEG measures also predicted decline in executive function and global cognition and identified stable individuals versus those who developed dementia. The findings were published in Stroke (October 2019, Vol. 50:10, pp. 2775-2782).

The group found no relationship between DSEG measures and information processing speed, perhaps because DSEG covers the entire cerebrum and not just white-matter tracts, with which information processing and small-vessel disease are strongly associated.

Charlton's team is developing an MRI analysis technique to predict vascular cognitive decline and dementia after ischemic stroke. Image courtesy and copyright of the University of London.

Charlton's team is developing an MRI analysis technique to predict vascular cognitive decline and dementia after ischemic stroke. Image courtesy and copyright of the University of London.The efficacy of DSEG needs to be validated using large-scale studies that follow patients over time. Research is also required to assess the utility of DSEG in small-vessel disease caused by events and processes other than ischemic stroke.

The technique is currently limited by the researchers' choice of a single healthy reference brain, which defines a narrow representation of the healthy aging brain. Charlton noted that the MRI arm of the upcoming Biobank study, which will acquire MRI scans, including DTI, from 100,000 individuals by the year 2020, should help with this.

"In the future, DSEG technology could be used as a decision-support system for clinicians," she said. "This technique has the potential to identify those patients at risk for cognitive decline and vascular dementia."

Catherine Steffel is a doctoral student contributor to Physics World. Catherine is pursuing a doctorate in the medical physics program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

© IOP Publishing Limited. Republished with permission from Physics World, a website that helps scientists working in academic and industrial research stay up to date with the latest breakthroughs in physics and interdisciplinary science.