Overdiagnosis underpins much of the controversy surrounding breast cancer screening, yet a new multinational study published in the International Journal of Cancer demonstrates overdiagnosis estimates vary widely based upon study design.

A team from Italy, Denmark, and the U.K. recreated the designs from five highly cited studies from various countries that found high rates of overdiagnosis, defined as more than 20%. Led by Sisse Helle Njor, PhD, from the department of public health programs at Randers Regional Hospital in Randers, Denmark, the group found the same data can give both high and low estimates of overdiagnosis, and it all depended on the study design and unmet assumptions (Int J Cancer, 6 April 2018).

"By this article we hope health professionals dealing with screening can see what the real magnitude of overdiagnosis is," Njor and one of her co-authors, Dr. Eugenio Paci, formerly from the Cancer Research and Prevention Institute in Florence, Italy, told AuntMinnieEurope.com. "Screening and clinical practice should consider overdiagnosis harm, but there is no reason for such emotionally polarized controversies as we have had in the last decades about mammography screening.

"Polarization is a consequence, the choice to transform a disagreement in methods and results in harsh social juxtaposition," they continued. "It's a very usual and easy choice in today's communication society, but very dangerous when based on unmet assumptions as in the overdiagnosis case."

Overdiagnosis risk: Overblown?

Overdiagnosis involves detection of lesions that would otherwise not become symptomatic in an individual's lifetime, and researchers estimate the frequency of overdiagnosis in various ways. For instance, de Gelder et al showed estimates comparing the number of overdiagnosed cases with the number of all cases limited to women ages 50 to 69 could be almost twice as high as estimates when comparing the number of cases in all women older than 50, i.e., continuing follow-up after screening ends (Epidemiologic Reviews, July 2011, Vol. 33:1, pp. 111-121).

A mammography examination is performed at the Randers Regional Hospital. Photos courtesy of Sisse Helle Njor, PhD.

A mammography examination is performed at the Randers Regional Hospital. Photos courtesy of Sisse Helle Njor, PhD.The resulting overdiagnosis indicators were labeled "women's perspective" and "population perspective" by the Independent UK Panel on Breast Cancer Screening. The panel concluded that three randomized controlled trials with long-term follow-up offered the most plausible estimates of overdiagnosis, 11% to 19% depending on the chosen perspective, according to Njor, Paci, and Matejka Rebolj, PhD, from the Centre for Cancer Prevention at Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine, Barts at Queen Mary University of London.

Njor's study grew from discussions between participants of the Methodology and Applications in Evaluation of Service Screening for Cancer Workshop held at the Wolfson Institute in May 2013.

"The reliance on randomized trials -- undertaken some 30 to 40 years ago -- in this and other reviews, e.g., that published by the Cochrane Collaboration, has, however, been criticized because continued screening in the intervention group after the trials had ended may have minimized the observed compensatory drop and thereby overestimated overdiagnosis," the authors wrote.

Without more up-to-date randomized controlled trials, overdiagnosis estimates have to be based on observational studies, which vary substantially from less than 10% to more than 30%. Some of the reviewed studies used the population perspective and others used the women's perspective.

"Comparison of overdiagnosis estimates is complicated by the fact the studies differed both in their populations and in study designs," the authors wrote. "The variability seems disconcerting even for experts, let alone for women considering their screening participation."

To reduce the complexity, Njor and colleagues compared data from a single population from Funen County in Denmark and provided empirical input for an appraisal of the different mammography overdiagnosis study designs.

The cohort study from Funen County followed previously screened women for up to 14 years after screening had ended. Using publically available data from Funen, they recreated the designs from the following high-estimate (more than 20%) overdiagnosis studies:

- Zahl PH, Tidsskriftet den Norske Legeforening, February 2012, Vol. 132:4, pp. 414-417

- Zahl PH, BMJ, April 2004, Vol. 328:7445, pp. 921-924

- Kalager M, Annals of Internal Medicine, April 2012, Vol. 156:7, pp. 491-499

- Jørgensen KJ, BMJ, July 2009, Vol. 339, p. b2587

- Jørgensen KJ, BMC Womens Health, December 2009, Vol. 9, p. 36

The researchers adapted study designs only to the extent they reflected the start of screening in Funen in 1993. The reanalysis of the Funen data resulted in overdiagnosis estimates similar to those from the original high-estimate age-period studies: 21% to 55%.

When breast cancer risk factors were accounted for, overdiagnosis rates halved. Rates fell even further when excluding never-screened birth cohorts. All told, Njor and colleagues found rates varied from 1% to 55%.

"By showing how much the way of doing the data analysis changed the results and explaining why some data analysis shows such high overdiagnosis estimates, we hope to be able to explain to doctors and health professionals what the real magnitude of overdiagnosis is," they told AuntMinnieEurope.com.

The wide variation stresses the need for a critical assessment of the assumptions underlying the most frequently cited approaches to estimating overdiagnosis, and the importance of an agreement between researchers about the methodology for overdiagnosis quantification, they added.

Suggestions for improvement

Pertinent to purely observational, nonrandomized studies of mammography overdiagnosis are estimating the incidence that would be expected in the absence of screening, and valid incorporation of the concept of screening-induced lead time into the analyses through observation of a compensatory drop, Njor and colleagues wrote.

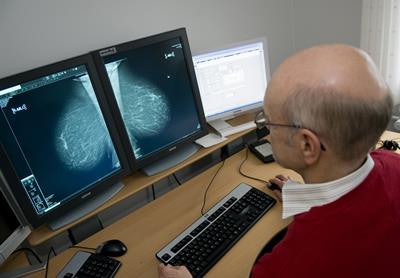

This photo shows the setup for reporting of breast scans at Randers Regional Hospital. Shown here is radiologist Dr. Anders Lernevall.

This photo shows the setup for reporting of breast scans at Randers Regional Hospital. Shown here is radiologist Dr. Anders Lernevall."Some important risk factors for breast cancer, e.g., breast density or overweight, have become more prevalent in recent years, in parallel with screening becoming more widespread," the authors wrote. "Historic breast cancer incidence rates from unscreened older birth cohorts are, therefore, probably too low and not representative for the currently screened cohorts without further validation."

Using the Jørgensen and Gotzsche studies as an example, the researchers estimated the expected incidence through a linear extrapolation of the prescreening incidence, which suggested 30% to 40% excess incidence due to screening in Funen. The same linear extrapolation in nonscreening Danish areas would result in an apparent excess incidence of 12% to 17%, demonstrating a linear extrapolation underestimated the true trends unrelated to screening, according to Njor and colleagues.

While it is possible to formally control for the changes in breast cancer risk in an age-period analysis, an adequate adjustment for lead time and compensatory drop is impossible without making additional assumptions that seldom hold.

"Studies should control for the background risk and include an informative selection of the studied population, as suggested recently in methodological work," the authors wrote. "Measures of the impact of overdiagnosis should be based on shared and unbiased methodological options."

High-estimate overdiagnosis studies in leading journals lead to a distrust of mammography and cause alarm in women, something they hope their paper will help remedy, they added.

The researchers plan to conduct a new study that looks at overdiagnosis estimates based on the incidence of low and advanced stages of breast cancer.