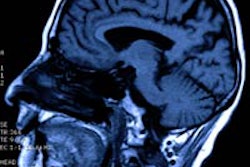

A new German study using functional MRI has shown what happens in the brain when a placebo is given, and it also highlights aspects that can help the doctor-patient relationship.

The placebo effect is one of the most exciting fields of research in medicine and neurosciences, and researchers today are gaining a much better understanding about why placebo can, for instance, relieve pain despite containing no active substance. Until recently it was assumed that a placebo intervention acted mainly on the frontal lobe and pain centers of the brain.

A study at Essen University Hospital has now shown that areas in the brain that are assigned to so-called reward centers are also active in this.

Patients should be made to feel they're getting an effective treatment, Dr. Nina Theysohn said.

Patients should be made to feel they're getting an effective treatment, Dr. Nina Theysohn said."These are the very same areas that also play a part in addictive disorders such as compulsive gambling," said Dr. Nina Theysohn, a radiologist from the Institute for Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology and Neuroradiology at Essen.

Many studies have already shown that placebo reactions are controlled by central nervous processes in which cognitive factors such as expectation play a part; if a patient believes in the effect of a medical intervention, pain can be relieved more effectively. This placebo effect is not confined to medicines because it also functions with other treatments such as sham acupuncture or even sham surgery.

In order to find out what happens inside the brain during a placebo intervention, 60 healthy subjects were studied at Essen University Hospital. The project was led by Theysohn and Dr. Sigrid Elsenbruch, a professor in the Institute for Medical Psychology and Behavioral Immune Biology. The subjects received a placebo preparation with a positive instruction or were told the truth about the administration of an ineffective saline solution.

Pain simulation

To simulate pain in the gastrointestinal tract, the researchers inserted a rectal balloon. The stretching of the intestinal wall was intended to simulate the pain suffered by patients with, for instance, irritable bowel syndrome, ulcerative colitis, or Crohn's disease.

"These are conditions which, according to current knowledge, also have a psychological component and are particularly associated with stress," Theysohn explained.

Functional MRI was then used to elicit the brain's response to various painful stimuli. It measured the activity of an area of the brain during pain, stimuli, or a cognitive process such as a mental exercise, by imaging the blood flow of the area concerned by means of highly sensitive sequences. The researchers also documented to what extent the trial subjects expected the medicine would help them overcome the pain.

Analgesics are perceived as a reward, which is important when communicating with patients. The subjects in the placebo group who had high expectations of the medicine activated so-called reward centers in the brain (nucleus accumbens and midbrain). Conversely, a low expectation led to activation of the classical pain centers (thalamus, cingulum, insula, prefrontal cortex).

"These findings indicate that it is not just the areas of the brain associated with pain and fear that regulate the placebo effect; other components are also involved," she commented. "If people think that a medicine will be beneficial, they sense this as a reward -- medicine as a form of 'treat,' so to speak. This is more of an interplay between the pain areas and the reward areas."

These findings are further evidence that good communication between doctor and patient has far-reaching consequences.

"Creating positive expectations in a patient is extremely important. Doctors should not just tell their patients 'If you take this medicine you may feel less pain,' or just focus the discussion on possible therapeutic failure or possible side effects. Patients should be made to feel that they are now getting an effective treatment that has also helped many other people," she noted.

Editor's note: This is an edited version of a translation of an article published in German online by the German Radiological Society (DRG, Deutsche Röntgengesellschaft) in collaboration with the German Society for Neuroradiology (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neuroradiologie). Translation by Syntacta Translation & Interpreting. To read the original article, visit the DRG website.