It's high time to start down the path to radiation dose transparency for coronary CT angiography (CCTA) -- as a mark of service quality, according to a hard-hitting guest editorial by a top U.K. cardiac imaging specialist writing in the British Journal of Radiology.

Quality is a difficult thing to measure publicly in radiology, but these days the quest for lower radiation dose is paramount, and the pursuit of low doses shows a commitment to protecting the patient, wrote Dr. Stephen Harden, president of the British Society of Cardiovascular Imaging and consultant cardiothoracic radiologist from University Hospital Southampton National Health Service (NHS) Trust.

Dr. Stephen Harden.

Dr. Stephen Harden.

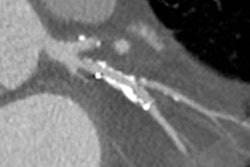

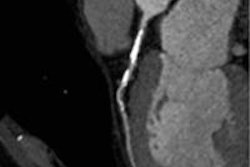

CCTA is an effective way to diagnose chest pain, and, despite the fact that some patients remain difficult to scan, plenty of studies have shown that high-quality images can be created at very low doses on newer scanners. Moreover, radiology and technology have done an admirable job of reducing the typical CCTA dose from 15 mSv to 30 mSv just a few years ago to sometimes less than 1 mSv today, he wrote.

"The biggest challenge of all is the change in our mindset," Harden wrote. "There is no reason why accurate, properly presented dose data should not be made available to the public on a professional society website" (BJR, March 2014, Vol. 87:1035, pp. 20130516).

Despite difficulties in implementing such a system, there are templates on which to begin, for example the experience of the Society of Cardiothoracic surgeons, which began publishing unit- and surgeon-specific mortality data in 2005.

Currently, 80% of all U.K. cardiac surgery units produce data for the audit, including tables that calculate risk-adjusted mortality based on the number of operations performed, and enable patients to compare how mortality data for their surgeon compare to that of other doctors, Harden wrote. In the wake of this project, cardiac surgery has embarked on the task of adding even more surgeon-specific quality markers.

"This process of transparency met with understandable caution and some resistance initially, but it is now accepted as part of the modern-day surgical practice," he wrote, adding that more surgical and subspecialty societies have since followed suit, with some data published in 2013.

CCTA has become a widely used tool for evaluating patients with chest pain owing to its accuracy for ruling out significant stenosis and for the high-quality images it produces. A few limitations, such as the difficulty of imaging patients with heavy coronary calcifications, seem to have been largely resolved with today's state-of-the-art scanners.

In fact, the biggest limitation to more widespread CT use has been the radiation dose, which typically ranged from 15 mSv to 30 mSv, which made the test difficult to justify compared with coronary angiography at 3 mSv to 6 mSv. But not so today, when the use of gated acquisition techniques, reduced tube current, and iterative reconstruction have drastically reduced doses to less than 1 mSv for some uncomplicated cases, Harden wrote.

"Should we therefore not take the next logical step and accept that radiation dose is a marker of quality practice?" he wrote. "It is reasonable to presume that cardiac CT units performing CCTA at low radiation doses are using all of the available techniques, which require attention to detail and a tailored examination for each patient."

But creating diagnostic images is the radiologist's job, and it's important to understand that some patients will always need higher doses, he wrote. Still, "the objective must be to provide high-quality care to all patients, and not create an environment where only simple cases that can be performed at low radiation doses are undertaken to obtain a low overall unit radiation dose," Harden wrote. Even cases that require higher doses are amenable to dose-reduction techniques, and difficult cases can still be matched and compared.

Doses can still be problematic in centers with older scanners, but in this case the need for lower published figures can be used locally to justify investments in state-of-the-art scanners, Harden wrote.

There is no reason why accurate data cannot be published on a publicly available society website, Harden concluded. "We can be transparent with this data, which are already collected, to demonstrate that we are providing a high-quality service anchored in patient safety," he wrote. Whether CT scans of other parts of the body are ready for similar scrutiny is not yet clear.