CHICAGO - Using a novel cardiac MRI technique, German researchers found significantly increased heart contraction rates in the left ventricle of healthy young adults one hour after they consumed energy drinks, in a study presented on Monday at the RSNA annual meeting.

The study group compared baseline images with those obtained after one hour using cardiac MRI with complementary spatial modulation of magnetization (CSPAMM).

Cardiac MRI with CSPAMM revealed significantly increased peak strain and peak systolic strain rates, which reflect contractility, in the left ventricle. CSPAMM also showed that stroke volume -- the amount of blood pumped from the left ventricle -- increased after energy drink consumption due to the higher peak systolic strain.

Dr. Jonas Dörner from the University of Bonn.

Dr. Jonas Dörner from the University of Bonn.

"The left ventricle is the motor of the heart," lead author and radiology resident Dr. Jonas Dörner, from the University of Bonn, said to AuntMinnie.com. It receives oxygenated blood from the lungs and pumps it to the aorta, which distributes it throughout the rest of the body.

Energy drink effects

There has been increasing concern over the potential side effects of energy drinks. The beverages generally contain taurine and caffeine as their main pharmacological ingredients. The amount of caffeine can be as much as three times greater than what is found in other drinks, such as coffee or colas. Taurine is a supplement added to the drink to enhance energy and performance.

Known side effects from high caffeine intake include rapid heart rate, palpitations, a rise in blood pressure, and seizures or sudden death in the most severe cases.

A 2013 report from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration stated that the number of emergency department visits in the U.S. related to energy drinks increased from 10,068 in 2007 to 20,783 in 2011. Most of the patients were 18 to 25 years old, followed by individuals 26 to 39 years of age.

"In Europe, energy drinks are very common right now, and there is an issue because even younger adults and children consume energy drinks," Dörner said. "We knew of this issue and we thought about doing contractility measurements in vivo using this [CSPAMM] tagging technique."

CSPAMM results

Dörner and colleagues scanned 20 male and 11 female volunteers with a mean age of 27.5 years (range, 18 to 35 years) before and one hour after consuming an energy drink that contained caffeine (32 mg/100 mL) and taurine (400 mg/100 mL).

Compared with baseline images, MRI with CSPAMM showed significantly increased peak strain and peak systolic strain rates in the left ventricle.

There were, however, no significant differences in heart rate, blood pressure, or the amount of blood ejected from the left ventricle of the heart between the volunteers' baseline and postconsumption MRI exams.

The results were somewhat unexpected, according to Dörner.

"We already knew that taurine and caffeine have a stimulant effect on cardiac contractility," he said. "We were kind of surprised as to how big the differences were because the concentration [of caffeine and taurine] we used for this study was not that high."

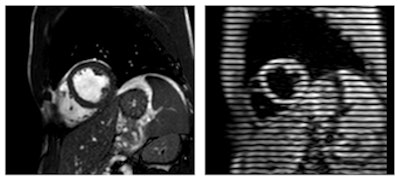

Images show a cross-section of the heart using common MRI techniques (left), compared with the tagged myocardium using CSPAMM (right). Images courtesy of RSNA and Dr. Jonas Dörner.

Images show a cross-section of the heart using common MRI techniques (left), compared with the tagged myocardium using CSPAMM (right). Images courtesy of RSNA and Dr. Jonas Dörner.As part of the study, the researchers also assessed the effect of a caffeine-only drink (iced coffee) with the same amount of caffeine as the energy drink in nine participants. Scans were once again obtained before and after consumption, and this part of the study was performed two to three weeks after the energy drink portion, so there would be no residual impact.

"We saw there was no significant increase in ejection fraction or stroke volume, and no significant change in peak strain or peak systolic strain rate," Dörner said. "So all the people who responded to the energy drink did not respond to caffeine alone."

Long-term effects?

While Dörner and colleagues concluded that energy drinks have a short-term effect on cardiac contractility, they do not know exactly how or if this greater contractility affects daily activities or athletic performance. Also unknown is the degree to which consumption may lead to an adverse cardiac event, such as a heart attack or arrhythmia.

"We cannot say if there is a risk for people with known heart disease, but that is a good question to answer in further investigations," Dörner said. "Because cardiac disease is not that obvious in people drinking energy drinks in high amounts -- and maybe in combination with alcohol or drugs -- it may be possible to have arrhythmia that can be harmful. We don't know that yet because all our subjects were healthy, with no known heart disease, and the dosages were very low."

Dörner and colleagues plan to continue their research with extended timelines to see how long the effects of energy drink consumption may last.

"It is already known that caffeine concentration can last four to six hours," Dörner said. "Taurine is different; it depends on the metabolism of each subject. So it's hard to say how long the energy drink effects may last."

In the meantime, the researchers recommend that children and people with known cardiac arrhythmias avoid energy drinks, given that changes in contractility could trigger arrhythmias.

They also advocate additional research to assess the potential risks of consuming energy drinks with alcohol.