Positron emission tomography (PET) has great potential for the future and promises to transform the practice of medical imaging, according to Dr. Stefano Fanti, Italy's national delegate for the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM).

Dr. Stefano Fanti from the University of Bologna.

Dr. Stefano Fanti from the University of Bologna.

In advance of the EANM's annual congress in Milan later this month, we interviewed Fanti about the current status and future development of molecular imaging (MI). He thinks radiologists should receive more training in functional imaging.

Fanti is a professor of radiological sciences and nuclear medicine at the University of Bologna, and he was assisted with his replies by co-worker, Dr. Cristina Nanni.

AuntMinnieEurope.com: Which definition of MI do you like most?

Fanti: The basic concept of molecular imaging relies on the need of approaches allowing us to explore the molecular pathways inside the human body in a noninvasive manner. This definition is quite simple, but at the same time exhaustive and appropriate.

Which single area of MI do you consider offers the greatest future clinical potential?

Given our common background, the response can only be PET. FDG-PET is indeed the single area of MI with the largest clinical application at present, especially in oncology, and holds further potential for developments. In the future, it's easy to predict that the use of other radiopharmaceuticals will widen the application in many clinical settings, from neurology to infective disease.

Do you believe that general radiologists are sufficiently interested in the potential of MI?

Dr. Cristina Nanni.

Dr. Cristina Nanni.

Many radiologists have shown great interest in MI, and some methods are simply in their hands, such as MR spectroscopy and MR diffusion-weighted imaging. However, the majority of radiologists outside academic institutions are not necessarily aware of the importance and progress of MI. In terms of their mindset, they probably feel more familiar and comfortable with anatomical imaging rather than with functional imaging.

Should molecular topics be given higher priority in radiological training?

In our view, a relevant part of diagnostic imaging in the future will be molecular, and therefore training in this area should be mandatory. In Europe, most nuclear medicine physicians are well trained in conventional radiology, given the close relationship between functional and anatomical imaging; conversely, most radiologists have minimal training in SPECT and PET. Probably the time has come to plan new common training in diagnostic imaging, with the emphasis and priority on molecular topics.

Overall, do you consider that Europe is lagging behind the U.S. in molecular imaging?

Regarding our area of interest, we feel that the U.S. and to some extent Japan are more active in the area of preclinical molecular imaging and basic research on PET. But during the last decade, Europe has overcome the rest of the world for clinical studies on innovative radiopharmaceuticals, maybe due to less restrictive legislation. As an example, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has just approved choline-11c for studying prostate cancer at the Mayo Clinic, while in Europe it has been used for a decade, and choline-18F has already been patented in France.

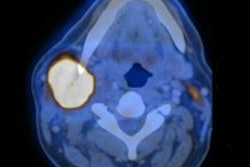

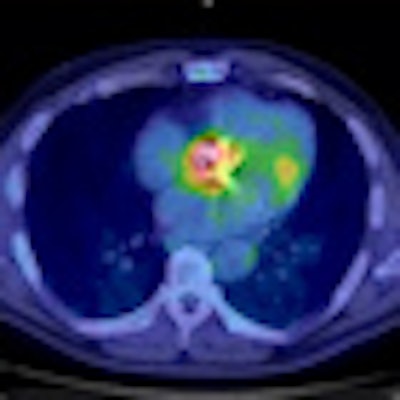

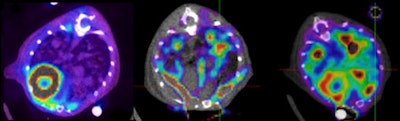

L-type amino acid transporter 2 (LAT2) transgenic mice PET/CT scan shows pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Left: F-18 FDG, middle: methionine-11C, right: choline-11C. All images courtesy of Drs. Fanti and Nanni.

L-type amino acid transporter 2 (LAT2) transgenic mice PET/CT scan shows pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Left: F-18 FDG, middle: methionine-11C, right: choline-11C. All images courtesy of Drs. Fanti and Nanni.Is sufficient funding currently available for molecular imaging research in Europe?

As a consequence of economic difficulties in Europe, funds for imaging research are definitely lacking, especially in the preclinical area. Nonetheless, many centers, mainly in the academic setting, remain very active. Probably the worst is yet to come, as the reduction of grants will negatively affect the number and quality of projects in the next decade.

Would you like to see greater reimbursement of MI procedures across Europe?

The main problem is the complete lack of a common European policy for reimbursement, which is still based on national rules. For example, in the area of PET, some indications for FDG scanning are fully reimbursed in some countries and not accepted in others (like Germany, which has a very restrictive environment); a tracer can be reimbursed in Italy and not allowed in the U.K. It would be extremely helpful to harmonize the situation, and the EANM is working on this topic.

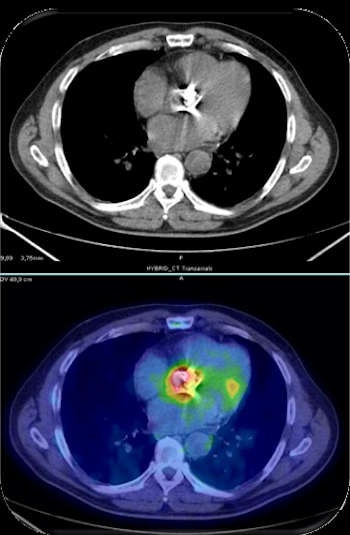

FDG-PET/CT scan of a human patient shows prosthetic valve endocarditis.

FDG-PET/CT scan of a human patient shows prosthetic valve endocarditis.What will be the central themes at your annual congress in Milan?

Plenary lectures -- focused on multimodality imaging in oncology, neurology, and cardiology -- are a must see. The symposia organized together with clinical societies are always very stimulating. After that, everyone should pick the sessions that are of interest to them. All sessions are always worth listening to, but you have to make your own choices. The EANM now has around 3,150 members, having grown from 2,129 in the year 2000, and this indicates how the association and its annual congress is growing in importance.

Are you optimistic about the long-term future of MI?

Yes, it will be a challenging time ahead, but a bright future exists for our field, especially if we are able to drive the process. We know that in vivo analysis of molecular expression at a cellular level allows an earlier diagnosis. This is already in clinical practice with PET, which has dramatically changed our capability to assess disease activity and extension. The next steps for MI include the synthesis of new radiotracers to increase specificity. Furthermore, a combination of different tracers and approaches will allow us to depict the exact molecular profile of the disease, leading to personalized therapies.

Editor's Note: The EANM 2012 congress runs from 27 to 31 October. For further details, click here.