February is the anniversary month of Image Gently, the global campaign to reduce radiation dose to children. So it's timely that the European Journal of Radiology has published an online article containing comprehensive dose-reduction recommendations for planning a pediatric CT examination.

Two factors always need urgent consideration: the size of the child and whether a CT exam is really needed. When a child has experienced severe and multiple traumas, a CT examination is essential. Otherwise, an imaging procedure with less radiation dose or no radiation may be the first to be performed.

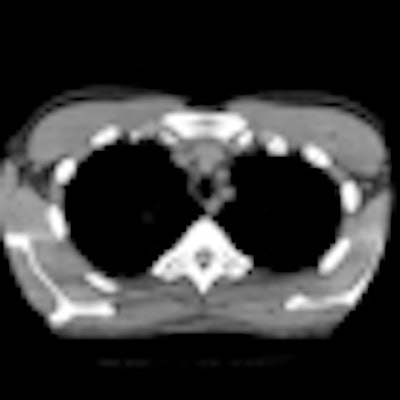

Chest CT images with reconstructions using different kernels; slices at the same position at the mediastinal level (Aquilion One, Toshiba Medical Systems). Left: Initial chest CT, reconstructed with the standard kernel (FC14). Right: Follow-up CT, reconstructed with a new, dedicated, dose-saving kernel (FC14). It becomes obvious that diagnostic image quality is maintained, despite more noise and artifacts using the new "dose-saving" kernel (right). All images courtesy of Dr. Erich Sorantin.

Chest CT images with reconstructions using different kernels; slices at the same position at the mediastinal level (Aquilion One, Toshiba Medical Systems). Left: Initial chest CT, reconstructed with the standard kernel (FC14). Right: Follow-up CT, reconstructed with a new, dedicated, dose-saving kernel (FC14). It becomes obvious that diagnostic image quality is maintained, despite more noise and artifacts using the new "dose-saving" kernel (right). All images courtesy of Dr. Erich Sorantin.But if the exam is merited, it should be performed with a 64-detector-row and higher CT system, or a volume CT scanner that has active collimation and faster scanning speeds to minimize the risk of overbeaming and overranging. Lead author Dr. Erich Sorantin, a pediatric radiologist and a professor at the Medical University of Graz in Austria, and colleagues recommend that radiographers consider all elements of a CT exam in which dose reduction might be possible, and to begin with the scout view (EJR, 8 January 2012, article in press).

Scout view length, tube position, and kilovolt (kV) and milliampere-second (mAs) settings all affect dose. By placing the tube below the CT couch, the dose can be one-third that of what would be needed if the tube was placed above the CT couch. The length of the scout view should be as short as possible with respect to the region that needs to be imaged to answer the clinical question. A laser finder should be used to facilitate exact positioning of the pediatric patient.

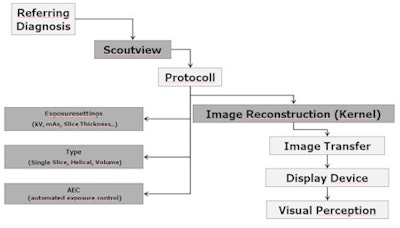

Imaging chain: Schematic overview of all steps of a CT study. The gray boxes represent those which can be manipulated on the CT console.

Imaging chain: Schematic overview of all steps of a CT study. The gray boxes represent those which can be manipulated on the CT console.Radiographers should not assume that fixed settings for the scout view should be used, the authors cautioned. They note that these are generally set for an adult body, and as one example, if used for an infant or small child, may add more than 50% dose in a single chest CT exam.

Setting appropriate kV and mAs parameters can be difficult, the authors noted. They recommend that variously sized phantoms be used.

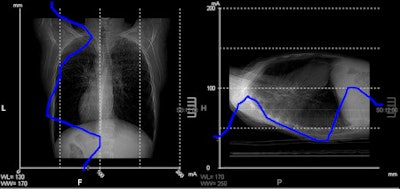

Scheme of possible tube position for scout views on a 320-detector-row CT (Aquilion One, Toshiba). It can be above ("top") or below ("down") the CT couch.

Scheme of possible tube position for scout views on a 320-detector-row CT (Aquilion One, Toshiba). It can be above ("top") or below ("down") the CT couch.

The authors explained the trade-offs of a patient's body diameter, slice thickness, radiation dose, and image noise, and noted that every scanner has a certain slice thickness with highest dose efficiency. This produces the best dose efficiency at the lowest diagnostically achievable dose.

The advantage of automated exposure control (AEC) is that it offsets image noise from a lower dose setting. To best take advantage of this for a pediatric patient, an appropriate scan slice thickness has to be chosen, and that the actual dose requirements may be less in infants and children, Sorantin warned. This necessitates changing settings to accommodate the body size of a child.

Anthropomorphic chest phantom for an adolescent. Direction-independent dosimeters were placed on each of the phantoms on several positions -- thyroid, upper and lower sternum, left and right anterior chest wall, bilateral on upper and lower lateral chest wall, as well as on the upper, middle lower spine.

Anthropomorphic chest phantom for an adolescent. Direction-independent dosimeters were placed on each of the phantoms on several positions -- thyroid, upper and lower sternum, left and right anterior chest wall, bilateral on upper and lower lateral chest wall, as well as on the upper, middle lower spine.

AEC functionality should control prospectively the dose demand with respect to the selected filter kernel used for image reconstruction. Dedicated kernels can reduce the delivered dose. When a reconstruction increment with 50% slice overlap is selected, this can reduce the partial volume effect without adding radiation. The use of iterative reconstruction algorithms have the potential to reduce dose up to 75% on the same image noise compared with a full-dose application.

Radiographers making dose adjustments also need to be aware that CT equipment differs considerably among models. When in doubt, radiographers should use recommendations posted on the website of the Society of Pediatric Radiology, and for general use, use 80 kV tube voltage for infants and 100 kV for larger children until they reach puberty, Sorantin recommended.

Pediatric CT exams with contrast should be performed knowing that infants have kidney immaturity and that children have an increased circulation time, causing arterial opacification to occur later than with adult patients. The authors offer suggestions in the article.

When performing CT on trauma patients, the radiology department at the Medical University of Graz starts with an unenhanced head CT, followed by a bolus tracking guided arterial phase acquisition covering the region from the Circle of Willis to the renal arteries. This CT scan can be used to assess the chest, vessel, and spine of the patient. Sorantin suggests that it be followed by a late-phase abdominal and pelvic scan. A pediatric radiologist should be present to immediately view the images and make decisions with respect to what additional exams are needed.

Screenshot from CT console depicting chest scout view. The horizontal axis represents the dose, the vertical axis slice positions -- the blue line indicating the dose requirements on a particular position at a given noise level. It can be perceived that on the lower chest part dose requirements approximate less than 25 mA.

Screenshot from CT console depicting chest scout view. The horizontal axis represents the dose, the vertical axis slice positions -- the blue line indicating the dose requirements on a particular position at a given noise level. It can be perceived that on the lower chest part dose requirements approximate less than 25 mA.In an unrelated article published online 29 December 2011 in the European Journal of Radiology, Dr. Padma Rao, a consultant pediatric radiologist at the Royal Children's Hospital in Melbourne, Australia, and colleagues provide advice about when and how to perform pediatric head CT exams. They recommend the use of a MRI exam if it is clinically feasible, but proceed to describe common indications when a CT exam is indicated.