The value of Wilhelm Röntgen's discovery of x-rays in 1895 to military surgery was appreciated immediately. The second half of the19th century was a period of rapidly changing military technology. The old soft lead bullets were being replaced by new steel jacketed bullets, and during the 1890s European armies were being issued the new powerful magazine rifles, including the Martini-Henry and the Mauser.

The new high-velocity bullets produced only a small entry wound and often passed straight through the body. The older gaping entrance wounds were no longer seen and army surgeons found that exploration for bullets was often more harmful than careful observation. The introduction of radiography helped in the development of modern war surgery by locating retained bullets. Although the early x-ray tubes were very fragile, the apparatus available before 1900 could detect fractures and foreign bodies.

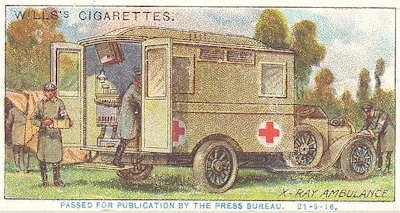

Radiology has played an important role in military history for more than 100 years. This illustration shows an x-ray ambulance during World War I. All images courtesy of Dr. Adrian Thomas.

Radiology has played an important role in military history for more than 100 years. This illustration shows an x-ray ambulance during World War I. All images courtesy of Dr. Adrian Thomas.The Abyssinian War

The first use of x-rays in warfare was in 1896 when Abyssinia was invaded by Italian forces. The Italians lost the battle at Adowa on 1 March 1896, and the casualties returned to the base hospitals in Italy by sea. Lt. Col. Giuseppe Alvaro of the military hospital in Naples successfully took radiographs of two soldiers with forearm fractures. These radiographs were made only six months after the discovery of x-rays and clearly showed the presence of retained bullets. Alvaro stated that the new technique "has proved to be a great aid in diagnosis, enabling us to determine with mathematical precision exactly where a foreign body was located."

The Greco-Turkish War

Hostilities broke out in the Balkans in the spring of 1897. The European nations were divided with Germany supporting the Turks and Britain, and Russia and France supporting the Greeks. The German Red Cross Society sent a medical unit to Constantinople and the London newspaper the Daily Chronicle sent two fully staffed and equipped hospital units to Greece under the British Red Cross in the charge of the surgeon Francis Abbott. The British equipment included a complete x-ray apparatus similar to that used at St Thomas' Hospital in London. Casualties were received from the Battle of Domoko, which took place on 17 May 1897. The x-ray apparatus was operated by Robert Fox Symons; Francis Abbott gave an interesting account of the difficulties experienced.

In Phalerum a room at the base hospital was set out for the x-ray equipment; Fox Symons had this installed and working by 1 June 1897. Casualties arrived soon after, and x-ray work continued for about six weeks. There were many difficulties, but overall the results were successful. Abbott and Fox Symons were able to illustrate their report about their activities with several radiographs and claimed to "record the first skiagrams taken in wartime, as well as to show that even inexperienced hands working can get fair results." The original prints were exhibited at the first conversazione of the Röntgen Society in London (this became the British Institute of Radiology), which took place in London on 15 November 1897. Abbott and his team treated about 114 patients with war injuries, and Fox Symons probably radiographed about half of them.

Abbott and Fox Symons' account of the use of x-rays under field conditions influenced the attitude of the British Army in following campaigns. Fox Symons had hoped it would be possible to use the fluorescent screen rather than taking photographic plates -- if the foreign body could be looked at in many projections, this would avoid the need for the slower process of obtaining a developed plate.

Fox Symons lists the technical difficulties as including the heavy weight of the coil and accumulators, the fragility of the Crookes (x-ray) tubes and glass plates, the dangers of transporting cases of sulphuric acid for the accumulators, the delicacy and temperamental nature of the apparatus, and the general problems of transportation. It was also said an additional source of difficulty was the superstition of the local inhabitants who looked at the x-ray apparatus and its use as the work of the devil. Fox Symons said it was difficult to take radiographs when the patient was constantly crossing himself to ward off evil spirits!

The most serious obstacle to field radiography was the lack of a reliable source of electrical power -- this prevented locating the x-ray apparatus where it would be most useful, which was at Khalkis in the hospital nearest to the front line. Even Phalerum did not have access to a main electrical supply, and so the warship HMS Rodney was used as the source of electricity to recharge the wet batteries.

The casualties were mainly cases of fracture or suspected retained bullets; in several patients, the bullets had penetrated the body cavities. The radiographic findings, in addition to helping with the immediate treatment of the patient, defined this new area of military medicine. Abbott wrote to the War Office stating, "The Roentgen rays should always, if possible, be available at the hospital nearest the front in which the wounds can be first properly examined and dealt with .... the apparatus is of no use in the field where detection can only be an incentive to premature exploration. The less wounds are tampered with before satisfactory surroundings are reached, the better. The modern bullet ... is practically aseptic and there is no urgency for removal."

The Tirah Campaign

In June 1897 there was insurrection in the Northwest frontier of India with Afghanistan. A British Army of 10,000 was sent to open the mountain passes. One of the groups was the Tirah expeditionary force consisting of 8,000 British and 30,000 Indian troops under the command of Gen. Sir William Lockhart. Twenty-three field hospitals were established on the Tirah plateau and 900 casualties were treated.

There was a long journey to the base hospital at Rawalpindi with transport being slow so the surgeons therefore treated wounds earlier and nearer to the front line. Walter Beevor, a regimental surgeon with the Coldstream Guards, examined 200 cases with x-ray on the Tirah plateau and later took further x-rays in the hospital at Rawalpindi. The examinations included the leg of Gen. Woodhouse whose leg wound had failed to heal, and some weeks later Beevor was able to show the retained bullet. Beevor made a presentation to the United Services Institution in May 1898, which signaled the introduction of field x-ray units into the British Army. It is interesting that Walter Beevor had purchased his apparatus at his own expense.

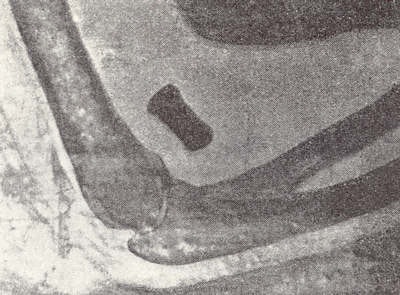

The illustration shows a radiograph of a bullet in the elbow of a native soldier taken by Maj. Beevor.

The illustration shows a radiograph of a bullet in the elbow of a native soldier taken by Maj. Beevor.The River War

A British-led army was sent from Cairo to the Sudan against the Mahdists whom they defeated at Omdurman on 1 September 1898. The army was led by Gen. Herbert Kitchener. The force was of 20,000 men, and they were equipped with modern weapons. Thomas Cook's pleasure boats took the army up the Nile as far as the cataract at Aswan. In the battle at Omdurman in daylight, 50,000 Mahdist tribesmen attacked this modern army with predictable results. They only had spears and primitive guns and the carnage was huge.

The army medical department had learnt from the experience of Surgeon Maj. Beevor and ordered a portable apparatus from A.E. Dean to be sent with the expedition, which was put in the charge of Surgeon Maj. John Battersby. He examined about 60 casualties with x-rays at Abadieh near Berber on the upper Nile between July and October 1898. His mud hut at Abadeih became a landmark in the history of radiology and of military medicine. The significance was that apparatus had been issued by the War Office as part of the regular medical supplies and it was the first use of x-rays in the field by the army medical department. The main difficulty experienced by Battersby was the climate in the Sudan, and it was with great difficulty the apparatus was made to work. Electricity was generated by a soldier using a bicycle.

One hundred and twenty-one wounded were transferred to Abadeih, and in 21 cases the conventional approach could not find a bullet. In 20 of these cases, an accurate diagnosis was made using x-ray, and in the final case the patient was too ill to be examined. Battersby concluded radiography prevented suffering by unnecessary probing of the wound, and in addition to simple radiography he used the cross-thread localization device of James Mackenzie Davidson.

The Spanish-American War

In the Spanish-American War of 1898, there was a limited use of radiography and again this avoided the need for unnecessary probing of the wound. The larger American general hospitals and three hospital ships were supplied with radiographic apparatuses. The American forces felt the use of radiography in the field was unnecessary because the bullet wounds rarely required immediate removal. It was also believed since aseptic surgery was not easy under field conditions, if the radiography could be obtained it would only encourage the surgeons to operate inappropriately.

Capt. William Borden published his document on the use of x-rays with an extensive account of the use of the new technique.

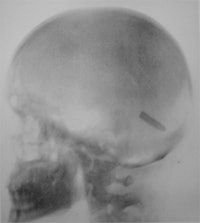

Private John Gretzer (left) received a bullet in his brain, which an x-ray detailed. Illustrated is a Mauser bullet in in the brain of John Gretzer (center) and the knee of Samuel Davis (right).

Private John Gretzer (left) received a bullet in his brain, which an x-ray detailed. Illustrated is a Mauser bullet in in the brain of John Gretzer (center) and the knee of Samuel Davis (right).

The abdomen of Walter Booth with an x-ray burn.

The abdomen of Walter Booth with an x-ray burn.

However, the technique was not without hazards and two cases of x-ray burns caused by repeated and prolonged exposure were described. Illustrated to the right is the abdomen of Walter Booth with an x-ray burn. Borden believed the most important factors responsible for the burns were the duration of exposure and the closeness of the x-ray tube to the patient.

The Boer War

In 1899 limited campaigns in South Africa started. The initial preparations were inadequate and what was expected to be a brief conflict turned into a full-scale war. The Boer War was the first occasion since the Crimea that the British Army faced an opponent with weapons as modern as their own, and who also had the moral advantage of defending their country against invaders. The war lasted two and a half years. There were 500,000 British troops in South Africa and fewer than 6,000 died in battle; more than 16,000 died of disease. The Boers lost the conflict with about 5,000 killed.

The medical arrangements became more complex as they progressed with a system of general (fixed) hospitals and field (moveable) hospitals. The x-ray apparatus was supplied to general hospitals as part of the essential equipment for the campaign; however, both electrical and radiation protection were still primitive. The general hospitals (but not the field hospitals) had portable x-ray apparatuses to allow retained bullets to be detected and fractures to be diagnosed and treated. The equipment was now supplied with a dynamo to generate the power needed for the batteries.

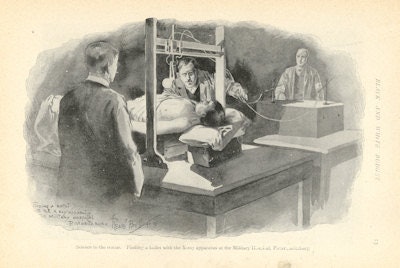

The illustration below entitled "Science to the rescue. Finding a bullet with the x-ray apparatus at the military hospital, Pietermaritzburg" is taken from the Black and White Budget of 1899. The dramatic image with the x-ray tube looking like a light bulb in the center above the patient shows the absence of both electrical and radiation protection that was characteristic of that time.

The illustration entitled "Science to the rescue. Finding a bullet with the x-ray apparatus at the military hospital, Pietermaritzburg" is taken from the Black and White Budget of 1899. The dramatic image with the x-ray tube looking like a light bulb in the center above the patient shows the absence of both electrical and radiation protection that was characteristic of that time.

The illustration entitled "Science to the rescue. Finding a bullet with the x-ray apparatus at the military hospital, Pietermaritzburg" is taken from the Black and White Budget of 1899. The dramatic image with the x-ray tube looking like a light bulb in the center above the patient shows the absence of both electrical and radiation protection that was characteristic of that time.World War I

The World War I was war with all its grim tragedy, and the large number of casualties put considerable stress on the casualty clearing or mobile field hospitals. At the start of the war, the x-ray equipment was located in the larger army hospitals behind the front. Initially, it was felt there was no need for facilities near the fighting; however, as the war progressed, the confidence of the army surgeons in rapid radiography increased and this was a view held by Marie Curie. In France, Marie Curie developed an x-ray car (voiture radiologique) and equipped 18 such cars herself. The engines of these cars could supply the current supply for the x-ray apparatus. Marie Curie also established 200 fixed radiographic units. As the war continued, the need for both radiologists and technicians increased. The French radiologist Antoine Béclère developed a training school at Val-de-Grace hospital and the French Army opened a school for x-ray technicians. Marie Curie opened a school for female x-ray technicians (manipulatrices) in 1916 and worked with her daughter Irène.

At the beginning of hostilities, the European armies were supplied with traditional gas x-ray tubes. During World War I, more powerful radiographic apparatus became available as the Coolidge tube and the Potter-Bucky diaphragm were introduced. The American expeditionary force was supplied with the best radiographic apparatus available, and these modern advances were used fully.

Following injury, the casualty was sent to a regimental aid post, then by field ambulance to the casualty clearing station, some miles behind the front. If radiography was required, then the patient was transferred to the x-ray room. Most of the x-ray work was in the detection of retained bullets, and a simple apparatus was used. The stretcher with the patient was placed on supports above a movable x-ray tube. The patient was rapidly fluroscoped, and using a parallax technique with tube movement, the depth of the foreign body and its relation to the point of entry could be determined quickly and a written report issued. The apparatus was powerful enough to diagnose thoracic injuries, and the use of stereoscopy was common.

Vincent Cirillo has demonstrated the importance of World War I for the development of the specialty of radiology. The army surgeons became accustomed to working in a team with radiologists and this practice continued after the war. The number of radiologists increased and the x-ray equipment became easier to use. World War I legitimized the discipline of military radiology.

World War II

By 1939 good portable apparatus was available. The British Army was supplied with the MX2, which was robust and easy to use. This apparatus could be used for radiography and fluoroscopy and was easily crated for transportation. Radiography had developed as a profession and many entered the forces; however, numbers available were inadequate and many units were only supplied with radiographers with no medical radiologists. In the U.S., two radiologists were assigned to each mobile surgical hospital unit. The work would consist of fluoroscopy of casualties, foreign body localization, general duties, and radiotherapy for superficial infections, including gas gangrene (prior to the introduction of antibiotics). Compared to World War I, the war was more mobile and radiographic units accompanied the field hospitals.

Conclusion

Military radiology has continued to develop since World War II. The military surgeons at the end of the 19 century soon realized the value of radiography in military surgery and innumerable lives were saved in the subsequent 50 years. As military technology developed, so did the technology to treat war casualties. We owe a debt to the early pioneers who initiated the development of military radiology, the need for which is still very much with us.

References

Nushida H, Vogel H, Püschel K, Heinmann A, Verlag K, eds. Florence Stoney and Early British Military Radiology. In Der durchsichtige Tote -- Post mortem CT und forensische Radiologie. Hamburg;2010:103-113.

Thomas A. The first 50 years of military radiology 1895-1945. European Journal of Radiology. 2007;63(2):214-219.

Vogel H, ed. The first 50 years of Military Radiology 1895-1945. In Violence, War, Borders. X-Rays: Evidence and Threats. Deutsches Röntgen-Museum/ECR 2008.

Dr. Adrian Thomas is chairman of the International Society for the History of Radiology and honorary librarian at the British Institute of Radiology.

The comments and observations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions of AuntMinnieEurope.com, nor should they be construed as an endorsement or admonishment of any particular vendor, analyst, industry consultant, or consulting group.