New portable ultralow-field MRI scanners promise to radically improve medical imaging access for patients with neurological disorders and other conditions, but which clinical indications and unmet needs will be filled with these systems? The global MRI community is striving to reach a consensus in this area.

Interest in the potential benefits of low-field MRI is gathering pace, and it is being boosted by recent hardware and software advances, improvements in imaging quality, its low cost compared with 1.5-tesla and 3T MRI, and promising findings from early research on their capabilities, according to Thomas Campbell Arnold, a doctoral student in the department of bioengineering at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Many hospitals can't afford high-field MRI systems and the physical infrastructure and staffing to run them, which cost millions of dollars, he told attendees at the annual congress of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM) in London. Devices such as those operating at 64 mT produce lower resolution images, but they weigh far less, can move around hospitals using a joystick system, are easier to store, and cost about $60,000 to $70,000 a year to operate, Arnold said.

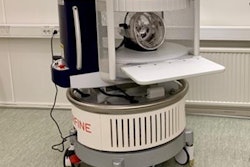

The Swoop portable MRI scanner from Hyperfine generated considerable interest in the technical exhibition at ISMRM 2022. The product won the Best New Radiology Device in the EuroMinnies 2022 awards scheme.

The Swoop portable MRI scanner from Hyperfine generated considerable interest in the technical exhibition at ISMRM 2022. The product won the Best New Radiology Device in the EuroMinnies 2022 awards scheme.He described his team's work examining low-field MRI in two neurological conditions: hydrocephalus and multiple sclerosis (MS). "We thought hydrocephalus would be essentially a slam dunk with this device -- a large pathology that would be easy to see," he said.

Arnold said this hypothesis was backed up by initial results of a small study that found there was comparable performance between low field and standard of care imaging for patients with hydrocephalus, although shunt settings had to be checked afterward due to magnetic interference.

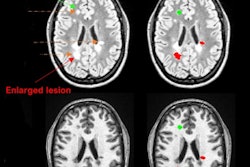

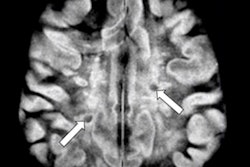

He said it was expected MS would be "very challenging," noting that "We wanted to see if white lesions could be detected and probe the true sensitivity limits of the (low field) system with smaller lesions."

Results from a study of 36 patients showed that in established MS, a portable 64 mT MRI scanner can identify white matter lesions, and disease burden estimates are consistent with 3-tesla scans. However, smaller lesions may be missed.

"Resolution, not contrast, appears to be the limiting factor in detecting lesions, which is exciting because with sequence development we can potentially increase the resolution of the system," he explained.

He said the potential for "super-resolution imaging" held out "exciting" possibilities for use and adoption of low-field portable MRI.

"A lot of work is being done trying to sharpen 3T Images into 7T -- we can do same thing at low field and make them look like they came from a high-field scanner." However, he said there was still a lot of work to be done before this method could be validated for clinical use in MS.

While the U.S. has 39 MRIs for every million people, in much of the world it is much lower and many countries have no MRI at all, said Arnold.

The U.K. experience

High-field MRI systems have presented major challenges for imaging the heart and lungs, including higher costs and the risk of heating metal devices, such as catheters, during imaging, said Adrienne Campbell-Washburn, PhD, a medical physicist at the National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London.

Adrienne Campbell-Washburn, PhD. Photo courtesy of ISMRM.

Adrienne Campbell-Washburn, PhD. Photo courtesy of ISMRM.She described her team's work on using a lower magnetic field but with higher performance elements. "To achieve this, we took a 1.5T system that was located in our cardiac path lab and we ramped it down to 0.055 T," she said at ISMRM 2022. "When we moved down to 0.055T, we reduced heating by an order of magnitude."

She said studies showed it was possible to produce high-quality images and the results suggested new opportunities for image-guided interventions. "We can use standard devices, standard imaging, and perform these procedures which is a huge leap forward."

Campbell-Washburn highlighted opportunities for cardiac and lung MRI using lower fields.

She said MRI systems were "really underused, particularly in the US because of the cost and complexity.

"So maybe low-field MRI is a good direction to increase the accessibility of the existing technology ... and to develop clinical applications that are not possible at 1.5T and higher field strengths."

At the bedside

Elena Kaye, senior scientist at Hyperfine, elaborated on how portable, low-field devices were being deployed at the patient's bedside.

Benefits included not having to move an unstable patient to a high-field MRI unit, which risked delays in treatment and adverse events in transportation, she said.

Kaye said the technology was "emerging" and image quality to support diagnosis would improve while early studies showing potential for clinical benefit required validation in bigger studies.

She said it was for hospitals to decide who should operate the scanners -- radiographers, nurses, or technologists.

"I'm sure there must be flexibility because in each hospital workflow might be different," she concluded.