VIENNA - Now more than ever, imaging is the mainstay of colorectal liver metastasis management -- first in terms of screening, diagnosis, characterization, and general staging, and then in terms of preoperative intrahepatic staging to determine resectability. Postoperatively, imaging is used to monitor recurrence and complications, and to evaluate tumor response and allow for treatment modification.

"Colorectal liver metastasis presents in all hospitals, no matter the size or specialty, so general and subspecialty imagers have to be part of the game," said Dr. Valérie Vilgrain, chair of the department of radiology at Paris 7/Sorbonne Cité University Hospital.

Colorectal liver metastasis is one of the most common metastatic diseases in the liver, and is usually a clear reflection of disease extent, given that the liver is the first organ of cancer migration from the colon. Between 30% and 50% of patients with colorectal cancer will have liver metastases, the latter often being diagnosed before the primary tumor. Because this metastasis comprises a major prognostic factor in colon cancer patients, management tends to be aggressive and as curative as possible.

"This curative approach requires a multidisciplinary, multimodality approach and combined treatment strategies," said Vilgrain, who will be speaking and moderating at today's multidisciplinary session.

Although colorectal liver metastasis is one of the top causes of cancer death, patient prognosis has improved dramatically compared with that seen five to 10 years ago, due to safer surgery and improved interdisciplinary collaboration between oncology and radiology based on more accurate characterization and preoperative staging.

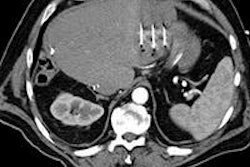

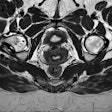

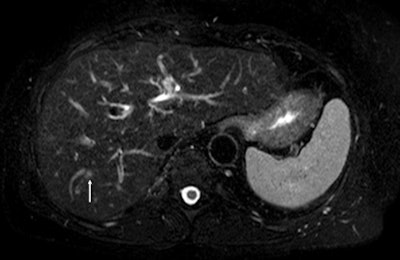

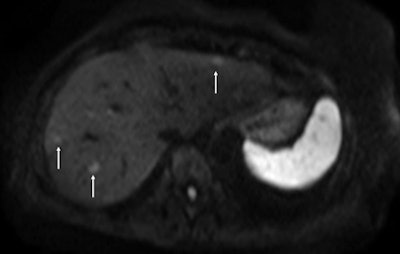

Above: Fat-suppressed T2-weighted fast spin-echo MR image obtained in a 61-year-old man with liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Only one metastasis in the right liver lobe is seen here (arrow). Moreover, this lesion is barely seen because it is located next to the vessel. Below: On the diffusion-weighted image, the same lesion is seen, as well as two additional metastases: one in the right liver and one in the left liver. All metastases are strongly hyperintense compared with the background liver at b = 600 sec/mm2, indicating restricted diffusion. All these lesions were surgically confirmed as metastases. Images courtesy of Dr. Valérie Vilgrain.

Above: Fat-suppressed T2-weighted fast spin-echo MR image obtained in a 61-year-old man with liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Only one metastasis in the right liver lobe is seen here (arrow). Moreover, this lesion is barely seen because it is located next to the vessel. Below: On the diffusion-weighted image, the same lesion is seen, as well as two additional metastases: one in the right liver and one in the left liver. All metastases are strongly hyperintense compared with the background liver at b = 600 sec/mm2, indicating restricted diffusion. All these lesions were surgically confirmed as metastases. Images courtesy of Dr. Valérie Vilgrain.

"Four years ago, intraoperative ultrasound sometimes revealed new lesions that had been missed in scans for staging colorectal liver metastasis. Now with diffusion-weighted MRI and the use of hepato-specific MR contrast agents, this is very unlikely to happen," she said, pointing to further details about surgical indications and candidates' prognostic factors to be provided by Dr. Jacques Belghiti, head of the department of hepatobiliary surgery, at the same Paris hospital.

In addition, preoperative patient conditioning such as portal vein embolization designed to increase resectability and reduce postoperative morbidity, as well as treatment strategies such as intra-arterial tumor ablation, are becoming more common, according to Vilgrain. Finally, better systemic chemotherapy or presurgery neoadjuvant chemotherapy is improving the success of resection and postsurgery long-time survival rates, as will be highlighted by speaker Dr. Sandrine Faivre, deputy head of service for the department of oncology at Paris 7/Sorbonne Cité University Hospital.

"Limitations remain. There is not always a close relationship between imaging and pathological findings. Tumor size is not sufficiently reliable, so functional tools are coming to the fore -- though there is still no consensus on monitoring tumor response through imaging," Vilgrain said. "We would also like to know in advance what the pathological response of a tumor will be after chemotherapy with or without adjunction of targeted therapy prior to surgery."

For pretreatment assessment, the focus of Vilgrain's presentation, it is essential to choose the correct treatment plan for the patient, and MRI plays a pivotal role in intrahepatic staging. CT is important for detecting extrahepatic involvement. If the metastatic liver is clearly resectable -- e.g., there are only a few lesions located in a limited, superficial area or confined to one liver lobe and the major vessels are not involved -- then the usual course is neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery. Imaging is still fundamental for monitoring neoadjuvant chemotherapy response, as surgery performed after no response has a poor prognosis, while even partial response to such therapy improves the prognosis for the resectable patient, she explained. If findings show a borderline case, imaging is still crucial for guiding treatment decisions and monitoring tumor response to chemotherapy.

Five to 10 years ago, the rules were hard and fast: Bilobar patients, or those with more than 10 lesions, were considered unresectable. But now these rules are no longer quite so strict.

"In 10% to 15% of patients considered unresectable, aggressive management can make them operable. These patients need regular monitoring and re-evaluation," Vilgrain said. "Secondary resectability rate varies from hospital to hospital, but 50% to 60% of 'borderline' cases do become clearly resectable after aggressive management."

To make borderline cases clearly resectable, some of the lesions in the affected lobe, or lobes, must be destroyed. Interventional procedures such as percutaneous tumor ablation or intra-arterial treatment can be undertaken at any stage before surgery or even intraoperatively.

Percutaneous ablation therapies have diversified from old techniques such as direct ethanol injection to multiple modality treatments, including radiofrequency ablation (RFA), cryoablation, acetic acid injection, laser ablation, microwave ablation, high-intensity focused ultrasound, and, more recently, irreversible electroporation, according to Dr. Mohamed Abdel Rehim, interventional radiologist in the department of radiology at Paris 7/Sorbonne Cité University Hospital, whose presentation at today's session will cover the role of image-guided treatment.

"Adding percutaneous ablation techniques to systemic chemotherapy achieves local control in a large majority of metachronous colorectal liver metastases, and new device innovations continue to allow for improved ablation zones and more durable results," he said.

If, surgically speaking, the liver remnant volume after such procedures is likely to be too small, then techniques such as preoperative portal vein embolization can increase remnant size to reduce postoperative morbidity.

Developments in technology, drugs, and technique also mean that more options are available for clearly unresectable patients who have many deep lesions in both lobes with vessel involvement. If there is no response to second- or even third-line chemotherapy, interventional techniques such as intra-arterial chemoembolization with specific drug-loaded particles injected into the hepatic artery to target the liver may yield better tumor control than from systemic chemotherapy, as may local internal radiation therapy in which yttrium-90 particles (Y-90, a pure beta-emitting isotope), are delivered to the hepatic artery for radioembolization of the metastasis.

"The indications for such intra-arterial treatments are increasing. In less advanced, possibly borderline patients, there is growing evidence to support the view that combined with systemic chemotherapy, such interventional treatment could improve outcomes," Vilgrain said.

While chemoembolization is a minimally invasive, safe, and possibly an effective palliative procedure due to its capacity to reduce lesion size, data suggest that radioembolization using Y-90 shows promise as a useful treatment for patients with chemotherapy-resistant hepatic metastases, according to Rehim.

"The maximum range of emission allows tissue only in close proximity to the embolized microspheres to be treated," he noted. "Studies show that with radioembolization, overall survival in a select patient population is improved compared to best supportive care alone."

Given that both general radiologists and cancer imaging specialists are confronted with pre- and postinterventional radiology procedures in imaging, his hope is that a broad range of ECR delegates will gain a deeper understanding of the different percutaneous or endovascular techniques available, and consolidate their knowledge about the evaluation of tumor response.

Originally published in ECR Today on 7 March 2013.

Copyright © 2013 European Society of Radiology