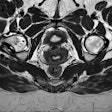

VIENNA - Breast MRI works well in a screening environment, according to results in more than 500 women who were examined in an Austrian national screening program. The modality could obviate the need for ultrasound for screening high-risk women, attendees learned on Thursday at the European Congress of Radiology (ECR).

Previous research has demonstrated that 5% to 10% of breast cancers are based on genetic mutations, according to Christopher Riedl from the Medical University of Vienna, who presented the study. A woman with a genetic mutation has a lifetime risk of breast cancer of 83%, and a 50% chance of cancer developing before the age of 50.

MRI has demonstrated its value for examining high-risk women, with use of the modality starting in the 1990s for this indication. Riedl described the university's experience with the modality since it began scanning women with genetic mutations in 1997; in 2002, the program began scanning women with a family history of breast cancer.

In reviewing the program, Riedl and colleagues wanted to answer several questions: What is the best way to perform breast MRI screening of high-risk women? What is the modality's sensitivity? What factors affect sensitivity? And which women are the best candidates for breast MRI screening?

The group scanned a total of 558 patients with an age range of 22 to 84 years and a mean age of 45. Some 156 individuals (28%) had the BRCA mutation, putting them at higher risk for breast cancer. Just over half (297 or 53%) did not have the mutation, while the mutation status of 105 individuals (19%) was unknown.

A total of 1,365 rounds of surveillance were completed, with suspicious findings in 204 cases (16%). There were 38 malignancies (19%), of which 18 (47%) were ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and 20 were invasive. Screening detected 38 of the cancers, while one was an interval cancer and one was detected as a BI-RADS 3 finding on MRI.

In terms of sensitivity, MRI outclassed both of the other modalities: Riedl's group reported sensitivity for breast MRI of 90%, compared with 50% for mammography and only 38% for ultrasound (p < 0.5). Indeed, 18 cancers, or 46%, were detected only on breast MRI.

MRI's advantage for DCIS was even higher, with the modality posting a sensitivity of 94%, compared with 50% for mammography and 28% for ultrasound. Nine cases of DCIS, or 50%, were found only on MRI.

MRI's higher sensitivity did come with a downside found on other breast MRI studies: a high rate of false positives. The modality's false-positive rate of 8% was much higher than that of either mammography or ultrasound, which both had false-positive rates of 2%.

Riedl and colleagues also analyzed their data by screening round to determine if there was a difference in diagnostic accuracy based on when individuals were screened. They found no difference in sensitivity for MRI, with ratings of about 90% for both the first and subsequent rounds, but they did find that the modality's specificity improved, from 85.2% in the first round of screening to 91.3% in subsequent rounds.

In an analysis of cancer incidence in the study population, the group investigated whether factors such as age, screening round in which cancer was detected, menopausal status, or mutation status affected incidence rates. No variable was statistically significant except for one: family history. Women with a family history of breast cancer had a cancer incidence of 6.7%, compared with 1.7% for those without such a history (p < 0.01).

The study indicates that breast MRI plays a positive role in screening women at high risk for breast cancer, and the large number of premalignant lesions it detects could reduce the incidence of invasive cancer down the road, Riedl concluded. In addition, the modality does not appear to be greatly affected by tissue density, with a sensitivity of 91.7% in women with low tissue density and 87.5% in women with dense breast tissue.

"We believe that the increased number of detected premalignant lesions might decrease the cancer incidence and improve risk stratification," Riedl concluded.

MRI's accuracy was such that screening programs for high-risk women could probably dispense altogether with ultrasound, the group also determined. "We didn't find a single case in cases where MRI was negative," Riedl said.