VIENNA - About a third of the CT scans performed in patients younger than 35 could be replaced by other modalities, concludes a Norwegian study presented Tuesday at the European Congress of Radiology (ECR). Meanwhile, a survey in the region of Essen, Germany, found that many pediatricians lack basic knowledge of radiation exposures for various chest indications.

CT overuse in Norway

Researchers estimate that at least 50% of the global radiation dose is caused by CT exams. And even though patients younger than 35 are more sensitive than older adults to the effects of ionizing radiation, the indications for which CT is used continue to rise worldwide, said Dr. Heljä Oikarinen, Ph.D., from Oulu University Hospital in Oulu, Finland.

Because studies show risk is much higher in patients younger than 35, the retrospective study of more than 200 patients aimed to determine "if the CT examinations done on patients under 35 years old were justified, and if they were not justified, whether a more justifiable imaging model had been available," Oikarinen said at the ECR session.

The study looked at exams performed on patients younger than 35 over a year's time, including 50 CT scans of the head and approximately 30 each of the lumbar spine, cervical spine, abdomen, nasal sinuses, and trauma.

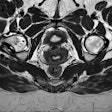

"We chose exams that we thought could be replaced by another examination if necessary. ... With CT of the lumbar spine, for example, MRI is indicated for evaluating disk syndrome of the lumbar-sacral area in young patients, while CT is usually indicated in trauma or punctural fixation," she said.

Abdominal cases were so variable, need had to be considered on a case-by-case basis. With head imaging, MRI is indicated in elective cases, whereas CT is justified in trauma, bleeding, and acute stroke, she said. In the sinuses, CT is indicated for functional endoscopic sinus surgery, and in the spine, CT is sometimes indicated in trauma cases.

Overall, about 30% (n = 59) of the exams being performed in the hospital weren't justified with CT. In the lumbar spine, 77% were unjustified, and in abdominal CT and CT of the head, about 35% were unjustified, according to the classification system the investigators had designed.

Thirty percent of the CT exams of the nasal sinuses could have been replaced, but all but one case (3%) of cervical spine CTs were justified, along with 100% of the trauma cases, Oikarinen said. Most of the cases could have been replaced with MRI, with fluoroscopy indicated in some abdominal cases.

"The justification for CT imaging should be carefully considered by both the referring practitioner and the radiologist performing the examination," Oikarinen said.

In comments heard after the talk, Dr. Patrick Rogalla from Charité Hospital in Berlin disputed the significance of the findings. While not performing CT would certainly provide the best radiation protection, the retrospective view of the study is of limited use in clinical practice, he said.

"You never have the same information before setting the indication for CT," he said. "When you make an analysis of the justification, you should also take into account that in a big percentage of the studies, we have different findings that were not the reason for performing the CT. So when we evaluate the utility we should consider the results of the studies -- even the ones that were not part of the indication."

Another member of the audience said that CT use in the U.S. is often driven by the lack of availability of MRI. Oikarinen said her hospital had ordered a second MRI scanner to alleviate that very problem.

German pediatricians lack dose knowledge

Speaking of referring practitioners, few pediatricians in Germany have a good understanding of radiation dose issues, according to a study from presented by Dr. Christoph Hayer from Ruhr-Universität Bochum in Bochum, Germany.

"Although we are on the radiology side, responsible for these radiation doses, we should not forget the clinicians who send us the patients," Hayer said in another ECR presentation at the pediatric dose session.

In published surveys of referring physicians, "many of the physicians had difficulty estimating dosages," while other studies suffered from low response rates or incomplete information.

To find out what hospital- and community-based pediatricians in Germany know about dose, Hayer and his team designed a questionnaire specifically tailored to elicit information about pediatric chest studies.

The survey's 75% response rate enabled direct interviews with 134 pediatricians, including 87 community-based and 46 hospital-based clinicians, to estimate effective doses for conventional radiographs and CT for different ages.

The participants were asked to provide the number of years of experience and average numbers of ordered examinations were documented, all anonymously.

The doctors were asked if they knew the degree of dose reduction possible in CT, if they knew about the ALARA (as low as reasonably achievable) dose principle, and if they were aware of studies suggesting a link between radiation exposure during CT and the risk of developing a malignant tumor.

The doctors were also asked how long they had been practicing, what subspecialty training they had received, and approximately how many imaging studies they had ordered per month or per year.

About half of the respondents had subspecialty training, Hayer said. The average length of professional experience was 16.9 years (range, 1-40 years). Significantly more imaging exams were ordered by hospital- compared to community-based physicians (p < 0.001).

"For every imaging modality, hospital-based pediatricians had statistically higher numbers" of imaging studies ordered, Hayer said. The number of ordered CT exams showed a significant negative correlation with length of professional experience (positive correlation -0.265, p = 0.002), "possibly indicating that experienced physicians more commonly rely on their clinical view," Hayer said.

While 41% correctly estimated the effective dose of an adult CT, 28% of respondents underestimated dose by a power of 10 or more. The effective dose for cardiac CT was significantly underestimated by 54% of respondents, while 56% undervalued the effective dose of CT without dose reduction.

Fourteen percent thought that MRI provides at least some radiation exposure. Only 4% came close to estimating the 96% dose reduction that could be achieved using dose-reduction methods; the rest underestimated it.

"Interestingly, neither the length of professional service, nor the kind of work, hospital-based or private, had any influence on those [two above] dose estimations," Hayer said.

Only 15% had heard of the ALARA principle, and fully 26% were unaware of the relationship between radiation exposure and studies about the risk of malignancy. Unfortunately, the answers to these last two questions revealed a significant positive correlation (p < 0.001) between the numbers of ordered CT and radiography exams and the rates of correct answers on the survey.

"Our survey demonstrated an increased awareness of radiation dose compared to the few dose studies that had been published to date," he said. "However, correct estimations of radiological chest examinations ... obviously pose substantial difficulties for pediatricians, regardless of the length of their professional training."

"Office-based pediatricians should become a part of the education process" to ensure that all pediatricians learn essential dose information, Hayer concluded.

By Eric Barnes

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

March 10, 2009

Related Reading

Radiation dose awareness leads to drop in pediatric CT usage, December 12, 2008

Swiss pediatric CT survey leads to national dose standards, October 23, 2008

Study: Radiologists dial back on pediatric CT settings, October 4, 2008

CT experts grapple with rising concerns about radiation dose, May 14, 2008

Teaching parents about CT risk might pare unnecessary scans in kids, December 28. 2006

Copyright © 2009 AuntMinnie.com