At one point this year, it looked like Europe's entire nuclear medicine sector would have to be put on hold, said Antonis Kalemis, PhD, president of Nuclear Medicine Europe (NMEU), the imaging industry group. When COVID-19 began spreading rapidly across Europe, industry felt huge anxiety as the lockdown measures escalated, but it has pulled together and survived.

"It was hectic," Kalemis told AuntMinnieEurope.com. "We had to move fast, improvise, and make lots of calls. But we adapted, made new arrangements, and kept the nuclear medicine sector going. And these adaptations have helped us avoid disruptions during the second wave."

Antonis Kalemis, PhD.

Antonis Kalemis, PhD.The task was fiendishly complicated, and the entire sector scrambled to respond. The challenge was to ensure that nuclear facilities could stay open, transporting nuclear materials despite travel restrictions, and keep hospitals supplied at a time of growing concern over infections. Kalemis, who is also business manager for molecular imaging at Siemens Healthineers, feared the restrictions could have ground the nuclear medicine sector to a stuttering halt.

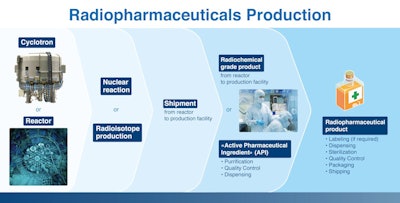

"The industry depends on a complex supply chain with different operators seamlessly connecting to one another," he commented.

Impact on radioisotopes

By mid-March, almost every European government had ordered drastic containment measures, which included travel bans, border controls, limits on nonessential journeys and shuttered businesses. Could radioisotopes still be made at nuclear processing facilities and shipped to hospitals and clinics?

"In the first weeks of the lockdown, we did not know what to expect," said Erich Kollegger, vice president of NMEU, formerly the Association of Imaging Producers and Imaging Suppliers, or AIPES. "We looked at all the potential issues. We put in social distancing. We asked many people to work from home. We stopped everything that was not related to production and maintenance. The whole world was learning, of course."

Demand for essential products like molybdenum-99 (Mo-99) fell by about 20%. However, many authorities recognized the value of continuity. For example, the Belgian government decreed on 18 March that the nuclear and radiological sectors were "essential services," ensuring the Belgian Reactor 2 nuclear reactor based in Mol, Belgium, could keep producing radioisotopes.

Nuclear medicine relies on a complex supply chain with different operators seamlessly connecting to one another.

Nuclear medicine relies on a complex supply chain with different operators seamlessly connecting to one another.Kollegger, who is also CEO of the Institute for Radioelements (IRE), says that his company eventually received guidelines for health and safety that mandated disinfectants, masks, and quarantines for infected staff. Facilities also took precautionary measure while producers modified their processing to align with flight schedules.

"This is a factory, and we have to keep operations going," he noted. "We had to work through the complexity, the costs, and the disruption to our supply chains."

Even after the industry found ways to keep producing radioisotopes, it still had to ship them to clients. The reimposed border controls for road transport were overcome when the European Union authorities designated nuclear medicine as an essential health service. EU countries even extended legal driving time hours to give more flexibility to transport companies.

Erich Kollegger.

Erich Kollegger.But air transport proved more complicated as most commercial flights -- the main carriers of radioisotopes and nuclear medicines -- were grounded. This was the biggest transport bottleneck: Alternative airports and air companies had to be found, and more than 60 new shipment routes were used.

"Until June, it was a permanent logistical fight," Kollegger pointed out. "Even when we found a flight, the departure airport could be different -- and the arrival airport as well. All that cumulates for the delay. And with radioisotopes, it is a race against the clock because even a couple of hours delay can mean you lose part of the product en route."

Major disruption

The disruption meant most nuclear medicine departments in hospitals lost between 15% and 30% of their full capacity. Some nuclear medicine departments shut down or reduced their daily routine to make space for additional ventilator beds or to reduce traffic.

"There were different impacts in different regions," Kalemis said. "In northern Italy and Spain, hospitals faced the most serious challenges: key personnel were moved to help COVID patients and that delayed treatments. A backlog built up, and even today, there are people in the U.K. who are still being delayed."

Amid the turmoil, imaging equipment was repurposed: many PET/CT and SPECT/CT systems were used for CT scans of COVID-19 patients, while where necessary gamma cameras could perform perfusion/ventilation or perfusion-only scans on lungs.

Now, as Europe slowly emerges from the second wave, Kalemis is still cautious about declaring victory. "It is a constant battle to keep nuclear medicine going safely and smoothly," he said. "At every point where the system could be disrupted, we worked out solutions. We developed containment guidelines, preventive and response strategies, and contingency plans to keep our facilities safe and supply chains open."

The pandemic may have created a new awareness about the importance of modern and effective healthcare. However, Kalemis says that his line of medicine faces challenges will long outlast the pandemic.

"We cannot put our activities on hold," he explained. "Cancer is not waiting until COVID leaves. Cancer patients are still fighting their battles. We need to keep supporting patients during this period and beyond, giving them the life-saving healthcare they need."

Global survey

An important survey of nuclear medicine professionals on this topic was conducted in April 2020. The results were published in the Journal of Nuclear Medicine in July 2020 by Dr. Lutz Freudenberg of the Center for Radiology and Nuclear Medicine Rheinland (ZRN Rheinland), Germany, and colleagues.

"Both diagnostic and therapeutic nuclear medicine procedures declined precipitously with countries worldwide being affected by the pandemic to a similar degree," the authors noted. "Countries that were in the post-peak phase of the pandemic when they responded to the survey, such as South Korea and Singapore, reported a less pronounced impact on nuclear medicine services."

Overall, the survey showed that nuclear medicine services worldwide were significantly impacted, and 15% of respondents experienced COVID-19 infections within their own departments.