A single complete compression ultrasonography scan can safely rule out a diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in women during pregnancy or in the first few weeks after giving birth, French researchers have found in a study published this week.

The risk of DVT increases during pregnancy, but accurately diagnosing it is difficult. Pregnant women often present with conditions that make visualization of the veins difficult, such as leg edema or a gravid uterus, and that interferes with the visualization of the proximal veins. Also, tests that are safe and reliable in nonpregnant patients are not always appropriate to use during pregnancy. Therefore, a multidisciplinary team led by Dr. Grégoire Le Gal, professor of internal medicinefrom Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de la Cavale Blanche, in Brest, France, assessed the safety of compression ultrasonography in pregnant and postpartum women with suspected DVT.

"The low prevalence of DVT and the need for a nonradiating diagnostic strategy in these women render noninvasive diagnostic tools highly appealing," noted the authors. "Single complete compression ultrasonography is widely used to rule out DVT in everyday clinical practice. No data are available to support this finding in the setting of pregnancy and the postpartum period."

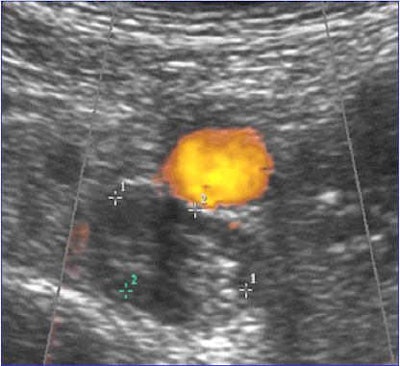

Ultrasound image of deep vein thrombosis. All images courtesy of Dr. Grégoire Le Gal.

Ultrasound image of deep vein thrombosis. All images courtesy of Dr. Grégoire Le Gal.The study, which was published online by the British Medical Journal on 24 April, included 210 pregnant and postpartum women referred for suspected DVT from two tertiary care centers and 18 private practices specializing in vascular medicine in France and Switzerland. The study period was January 2006 to June 2009.

The researchers used high-definition B-mode ultrasound equipment, with different probes according to the depth of the examined vessels. Iliac veins were visualized by direct imaging and Doppler flow. The whole venous network was scanned bilaterally; the inferior vena cava and iliac veins with the patient supine or in the contralateral position, femoral veins (common, superficial) and popliteal veins with the patient in a semi-upright position, and calf veins (posterior tibial and peroneal) with the patient in a sitting position and both feet resting on a chair.

Study of the distal veins included the posterior tibial and peroneal veins, the gastrocnemius (internal and external), and the soleal veins, using different incidences. All of these venous segments were examined over their entire length in the transverse or longitudinal axis. The great and small saphenous veins were also studied at their junctions with the deep venous system. Special attention was paid to whether doctors were able to image all veins, in particular the ileocaval junction. All ultrasound examinations were performed by vascular medicine specialists with at least 10 years of experience in vascular ultrasound.

A single compression ultrasound scan was performed on each patient, and anticoagulant therapy was given to those with a positive result. All women were followed up for three months. DVT was diagnosed in 22 (10.5%) of the 210 women. Of the 177 patients without DVT and who did not receive anticoagulant therapy, two patients (1.1%) experienced a confirmed DVT during follow-up.

"Although this study is one of the largest available studies in the setting of pregnant and postpartum women, the sample size was relatively small, which could explain the wide confidence interval," they wrote. "The 4% upper bound we observed is in line with the results of a previous management outcome study in pregnant women, which reported a three-month venous thromboembolis risk of 1/137 after negative serial proximal compression ultrasonography results -- that is, a risk of 0.7% (95% confidence interval 0.4% to 4.0%)."

The study limitations, as well as the upper limit of the 95% confidence interval around their estimate of the three-month risk of a thromboembolic event, prevent them from drawing firm conclusions.

Multidisciplinary research on thrombosis is taking place at Brest's Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de la Cavale Blanche.

Multidisciplinary research on thrombosis is taking place at Brest's Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de la Cavale Blanche.

"Further investigations should aim at confirming these results and evaluating the use of compression ultrasonography in a sequential diagnostic strategy including assessment of clinical probability and D-dimer measurement," the authors wrote.

It is important to keep aware that isolated iliac venous thromboses, which may beencountered more often in pregnancy, are more difficult to diagnose by compression ultrasonography because the usualaccepted criterion for DVT -- lack of compressibility of the veins -- may be difficult to evaluate at theiliac level in pregnant women, they stated.Also, pregnancy is associated with changes in the anatomy and physiology of veins -- i.e.,an increased vessel diameter and reduced flow velocity.These physiological changes are associated with technical difficulties for the ultrasound examination, and they may persist for days orweeks after delivery.

Gal adds that the multidisciplinary clinical research group for thrombosis comprises internal medicine, respiratory, nuclear medicine and vascular medicine physicians, along with hematologists and radiologists.

"We carry out epidemiological, therapeutic, and diagnostic studies in the field of venous thromboembolism," he said. "We currently have an ongoing study on the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism in pregnant women. We plan to undertake another study on the diagnosis of DVT in pregnancy, in order to confirm the results of the present study, and to assess emerging diagnostic tools in this setting, in particular the LEFt score developed by Chan et al."