Not everything that glitters is gold, and not everything that enhances in breast MRI is due to breast cancer. That was one of the core messages of Prof. Dr. Christiane Kuhl, PhD, chair of radiology at Aachen University Hospital in Germany, in her ECR talk on how to identify malignant lesions on MRI.

"The art is not to find breast cancer but to accurately distinguish benign from malignant enhancement," said Kuhl at the rising stars' session on 5 March, noting that it is important to avoid misdiagnosing lesions with seemingly benign morphology.

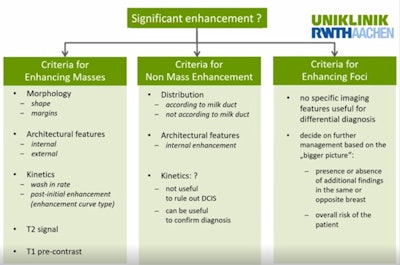

Once radiologists have decided there is significant enhancement that goes beyond the normal enhancement of fibroglandular tissue, known as benign parenchymal enhancement, they need to distinguish whether it is an enhancing mass or non-mass enhancement or an enhancing focus, she said.

An enhancing mass is enhancement that has a correlate on precontrast T1- and T2-weighted imaging, whereby a mass effect, or a 'space occupying' lesion is visible. In these enhancing masses, the differential diagnosis is between invasive cancer and benign tumors such as fibroadenoma or papilloma.

The main criteria and points to remember about breast lesion enhancement. All figures courtesy of Prof. Dr. Christiane Kuhl.

The main criteria and points to remember about breast lesion enhancement. All figures courtesy of Prof. Dr. Christiane Kuhl.Non-mass enhancement, on the other hand, has no correlate on precontrast T1- and T2-weighted images, no mass effect, and normal-appearing parenchyma at the site of enhancement, Kuhl continued. In this enhancement type, the normal differential diagnosis is between ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), or diffusely infiltrating cancer, and benign entities such as adenosis, hormonal stimulation, and the normal breast with benign parenchymal enhancement.

Meanwhile, an enhancing focus is a special case of non-mass enhancement over an area no larger than 5 mm in diameter, which is too small to characterize. The decision to biopsy will be taken in line with the 'bigger picture,' such as presence of breast cancer elsewhere in the same breast, she said.

In significantly enhancing masses or non-mass enhancement, characterization will be based on specific criteria, and these criteria are different for mass versus non-mass enhancement.

For enhancing masses, we use criteria related to morphology, including shape and margins, internal and external architectural features, kinetics, wash-in and wash-out rates, T2-weighted signal, and T1-weighted precontrast signal, she explained. For non-mass enhancement, criteria are limited to distribution, internal architecture, and symmetry.

Benign mimics

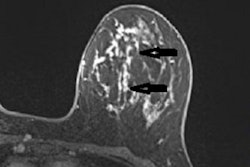

For characterization of enhancing masses, a tumor's internal enhancement is one of the most powerful criteria for characterization of mass-related enhancement, according to Kuhl. Internal septations within a mass suggest a benign fibroadenoma, while on the other end of the spectrum, rim enhancement is highly typical of breast cancer. This rim enhancement is particularly useful in high-grade cancers whose morphology tends to mimic fibroadenomas in terms of oval shape and smooth margins.

External architecture (i.e., growth pattern of masses) in respect to Cooper's ligaments will also provide clues. There may be a growth pattern across Coopers' ligaments, which is typical of breast cancer, or along Coopers' ligaments, which is more typical of benign tumors.

Radiologists should check for tumor growth in relation to Cooper's ligaments, the bands of tough, fibrous, flexible connective tissue that shape and support breasts.

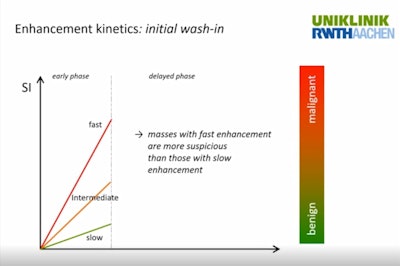

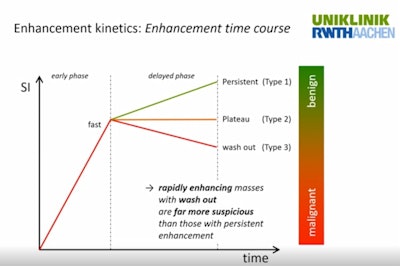

Radiologists should check for tumor growth in relation to Cooper's ligaments, the bands of tough, fibrous, flexible connective tissue that shape and support breasts.In terms of enhancement kinetics, we assess early-phase enhancement (wash-in) as well as the signal intensity time course in the post-initial and late phase, she said. Wash-in can be slow (suggestive of benign tumors) or fast (more typical of malignancy). A further analysis of signal time courses is only useful for lesions with masses with fast enhancement. Only in those cases should radiologists decide whether or not the enhancement is persistent, reaches a plateau, or if there is wash-out, she recommended. Typically, enhancing masses with strong wash-out are far more suspicious than those with persistent enhancement.

"To analyze enhancement kinetics, we used to place regions-of-interest to yield curves of signal intensity over time, but we hardly do this any more. Rather, the MR scanner or PACS must allow you to loop through the dynamic phases of a given section to watch enhancement over time in a given lesion and identify wash-out in a lesion. This is far better than trying to see the wash-out based on a juxtaposition of images. Don't use a multi-image hanging protocol to analyze kinetics. It's a pest and will not work," Kuhl said.

Fast enhancement is indicative of cancer in masses.

Fast enhancement is indicative of cancer in masses. Strong washout in benign-looking lesions with fast enhancement is indicative of high-grade cancer.

Strong washout in benign-looking lesions with fast enhancement is indicative of high-grade cancer.Analysis of enhancement kinetics is particularly useful in enhancing masses with fast enhancement and with benign-appearing or equivocal morphologic features, where strong wash-out will be indicative of high-grade invasive cancer.

Another helpful criterion to classify masses with fast enhancement and seemingly benign pathology is T2-weighted signal intensity. Low signal intensity on non-fat-saturated T2-weighted images is suspicious because breast cancer shows dark, about as fibroglandular tissue, while fibroadenomas with fast enhancement are brighter. The only exception is mucinous breast cancer, which has a very bright signal on T2 equivalent to water due to the mucin that fills up the cancer cells, Kuhl explained.

Benign tumors have higher signal on T2-weighted images, with the exception of mucinous breast cancer.

Benign tumors have higher signal on T2-weighted images, with the exception of mucinous breast cancer.The final criterion -- T1-weighted pre-contrast signal -- is particularly helpful for differentiating enhancing masses with rim enhancement. In non-fat-saturated images, high signal intensity in the center of masses with peripheral enhancement is indicative of a benign process. It indicates conditions such as complicated cysts, fresh fat necrosis, intramammary lymph nodes, and hematoma.

Malignant asymmetry

Kuhl then explained about criteria useful to classify non-mass enhancement. In these cases, radiologists use distribution, internal architecture, and symmetry; enhancement kinetics are used only to corroborate positive findings.

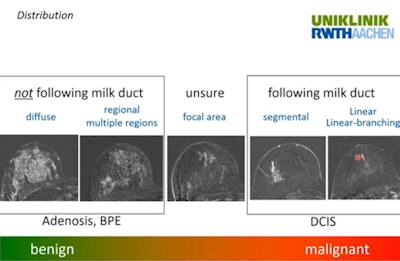

First, radiologists must decide if distribution follows the milk ducts or not. Segmental or linear-branching enhancement that follows or imitates the milk ducts is indicative of DCIS, while enhancement that does not follow them, that is diffuse, regional, or in multiple regions would suggest that the lesion is benign, possibly adenosis or benign parenchymal enhancement.

Symmetry is the most powerful criterion for characterization in non-mass enhancement. Comparison of both breasts will show if enhancement is bilateral and more likely due to hormonal changes, or unilateral and indicative of DCIS or lobular cancer. Any unilateral, asymmetric enhancement in the inner portion of the breast should raise suspicion of malignancy, while if hormonal stimulation presents as unilateral, it is usually on the outer portion of the breast, she said. Of note, symmetry must be compared by considering enhancement in the entire left versus entire right breast -- and not for a given section.

Ask yourself: Does distribution follow the milk ducts?

Ask yourself: Does distribution follow the milk ducts?Meanwhile, care needs to be taken with enhancement kinetics in non-mass enhancement: benign-appearing (i.e. moderate/slow persistent enhancement) does not obviate the need for biopsy because malignant lesions that are associated with non-mass enhancement (i.e. DCIS or diffusely-infiltrating lobular cancer) are typically not associated with strong angiogenic activity. Hence, in non-mass enhancement suspicious of DCIS or lobular cancer, kinetics can only be used to confirm diagnosis, but not to rule it out, Kuhl noted.

Question and answer time

In the Q&A session after Friday's talks, moderator, Prof. Dr. Francesco Sardanelli, director of radiology at the San Donato clinic in Milan, asked Dr. Tamar Sella, director of the breast imaging unit at Hadassah Hebrew University Hospital in Jerusalem, what should happen in practice when biopsy brings no corroboration with radiological findings. Sella, who presented on inflammation and benign lesions, recommended rebiopsy when the radiologist's suspicion is contraindicated by the pathological result.

Either the lesion was not correctly sampled, or there might have been a mix-up with different samples in the lab, she stated, pointing to possible mistakes.

"If it looks malignant you need to consider it being malignant," Sella said. "Either rebiopsy it, send it for surgical excision, or do an MRI if you think this will make things clear to you, but you cannot leave it alone and say 'OK, the biopsy was benign' and let it go."