The effect of breast screening is stronger and longer-lasting in women who are 65 and old, but it remains highly relevant for younger women, according to new data from England published on 23 November in the British Journal of Cancer (BJC).

The National Health Service (NHS) breast screening program case-control study of over 23,000 women showed a 37% reduction in mortality for women screened at least once, corresponding to approximately nine breast cancer deaths prevented between the age of 55 and 79 for every 1,000 women attending screening between the ages of 50 and 69.

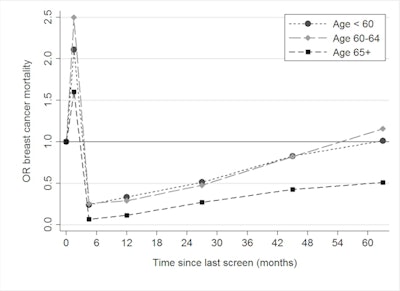

Measures of the benefit of screening are largely influenced by the consequent reduction in mortality from symptomatic cancers, noted first author Roberta Maroni, a statistician at the Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine, Queen Mary University of London. Screen-detected cancers -- defined as the ones diagnosed within three months of a screen -- represent a larger proportion of the cancer-related deaths in the immediate period after a screen, despite being less fatal overall. The spike in excess mortality in the figure below illustrates this point.

The duration of the benefit of attending screening appears to be greater in older women (OR = odds ratio). All figures courtesy of Prof. Stephen Duffy and the BJC.

The duration of the benefit of attending screening appears to be greater in older women (OR = odds ratio). All figures courtesy of Prof. Stephen Duffy and the BJC.Overall, the England-wide study showed that, despite major improvements in diagnostic techniques and treatments, mammography screening continues to play an important role in lowering the risk of dying from breast cancer.

"We expected to find a benefit in terms of reduction of risk of breast cancer death. We were slightly surprised at how large it was, and how it remained relatively large after adjusting for potential from self-selection (healthy volunteer bias)," corresponding author Prof. Stephen Duffy, a professor of cancer screening at Queen Mary University, told AuntMinnieEurope.com.

Impact of the pandemic

Duffy thinks it was absolutely correct to halt the frontline screening activity in late March. He believes the service has been doing what it can to recover and that it began doing so as soon as was practically possible.

"We screen two million women a year in the U.K., and it is clear that with precautions against COVID transmission, we are not able to have the same speed of throughput as before," he explained. "I am uneasy about the use of open invitations instead of timed appointments, but I understand the motivation in terms of the reduced number of screening slots available."

The NHS breast screening program is doing its job in reducing the risk of death from breast cancer, he continued. "Our results indicate that the benefit persists for 3-4 years in women aged under 65, so slippage of the three-year interval would be unsafe for these women."

Duffy emphasized that in the current COVID-19 crisis, efforts to reinstate the breast screening program must continue apace. "If difficult decisions about delivery of the program have to be made in the future, it may be appropriate to consider different intervals between screens for different age groups."

Other key findings of new study

Returning to the BJC study, the authors' table below summarizes the main results without and with correction for self-selection bias.

| Results of the matched logistic regression evaluating the association between screening attendance and breast cancer mortality | ||||||

| Exposure | Category of exposure | Controls (n = 15,202) |

Cases (n = 8,288) |

OR (95% CI) |

OR (95% CI) corrected for self-selection1 |

OR (95% CI) corrected for self-selection2 |

| Ever screened | ||||||

| No | 1,803 | 1,741 | 1.00 | - | - | |

| Yes | 13 399 | 6 547 | 0.49

(0.45-0.53) |

0.62

(0.56-0.69) |

0.63

(0.55-0.71) |

|

2 Self-selection correction performed using the second method (Duffy et al, as above).

Using data from cervical screening attendance, the self-selection correction factor was estimated to be 0.78 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.73-0.84). The primary endpoint -- the association between attending one or more screens and death from breast cancer -- had a resulting odds ratio (OR) of 0.49 (95% CI, 0.45-0.53) and, when corrected for self-selection, had an OR of 0.62 (95% CI, 0.56-0.69) by the first method and an OR of 0.63 (95% CI, 0.55-0.71) by the second.

Using the second method, the estimate of the effect of invitation to screening was a 26% reduction in breast cancer mortality (OR = 0.74; 95% CI, 0.68-0.81).

"The unmatched logistic regression on the larger dataset for sensitivity analyses showed a similar effect of screening on breast cancer mortality both before and after controlling for age at diagnosis/pseudodiagnosis and screening area (in both cases, uncorrected OR = 0.55, 95% CI 0.51-0.59)," the authors wrote.

The findings suggest that the effect of a delayed screen in older women has a lesser consequence for increased risk of breast cancer mortality than it would have had in younger women. While the U.K.'s three-year interval is longer interval than other programs in Europe and North America -- and further slippage of the interval should be avoided, they emphasized -- these results could also be used as guidelines for screening units at times of capacity constraints, with the provision that all women receive an opportunity for a final screen around or shortly after age 70.

A limitation to the study is the retrospective design and the potential for self-selection bias. What's more, case-control studies for cancer screening programs are subject to an inherent type of anti-screening bias known as screening opportunity bias, the researchers conceded.

Looking to the future

The Queen Mary team is now working on estimating the effects of the hiatus due to COVID-19 on likely breast cancer outcomes over the next 10 years.

"We are also carrying out a number of studies of the effect of the screening programme on disease incidence (overdiagnosis), disease stage and treatments," Duffy said. "We are also involved in studies of additional or alternative imaging modalities in breast screening, including automated ultrasound, tomosynthesis, and abbreviated MRI."